Mobile operating systems market shares

With the rise of smartphones and the constant evolution of technology, the rivalry between iOS, Android and Windows becomes more and more intense. The market shares for each operating system vary inventively depending on several factors.

Mobile operating system market growth forecast in 2024

According to recent reports smartphone sales have increased, driven by the growing adoption of 5G and the new iPhone. This is thought-provoking about the mobile operating system growth forecast for 2024.

Android gets a head start

Between Android and iOS, competition is fierce. However, it seems that Android is taking a head start by becoming the number 2 mobile OS according to a Gartner analysis. It should be noted that in France, the success of the iPhone allowed Apple to grow by 4.2%. Furthermore, the meteoric rise of HarmonyOS makes it a potential competitor that could even supplant iOS in China.

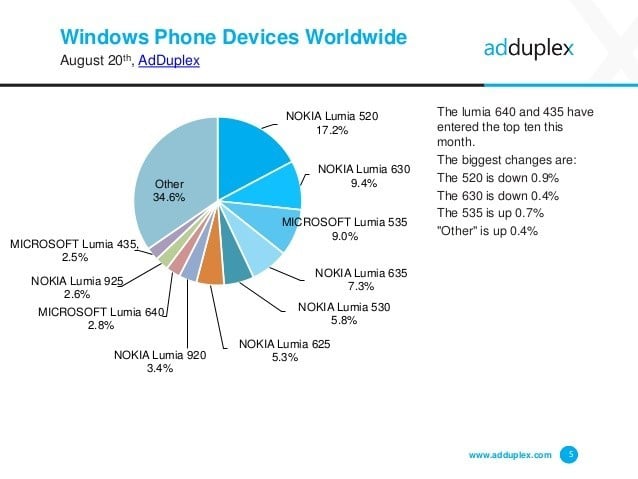

The fall of Windows Phone

Concerning Windows, the situation is rather delicate. Windows Phone sales have fallen drastically, indicating a decline in Microsoft’s mobile operating system. Whether this is a disaster or a strategy remains a matter of debate among market analysts.

Impact of Apple’s new rules on advertising

Beyond growth forecasts, Apple’s new policies have a considerable impact on the market. For example, recent changes to advertising regulations have seriously affected Criteo, a leading digital advertising company turned unicorn.

ARM processors and the laptop market

The evolution of mobile operating systems is having a snowball effect on other segments of the technology market. ARM processors, commonly used in mobile devices, are predicted to account for 25% of the laptop market by 2028.

Samsung dominates the global smartphone market

When it comes to the smartphone market, Samsung establishes itself as the global leader for the third quarter of 2023. This success strengthens the position of Android, the operating system on which most Samsung smartphones run.

Detailed market share comparison between iOS, Android and Windows in 2024

2024 marks a new era for mobile operating systems. Being equipped with a good operating system has become an essential necessity to guarantee the security and efficiency of our devices. With iOS, Android And Windows as major players in the market, a comparative analysis of their market share is necessary.

iOS supremacy on the market at the end of 2022 and 2023

At the end of 2022, theApple iPhone achieved a feat by rising to first place in the global mobile operating system market. A remarkable performance that demonstrates the excellence of Apple technology and its ability to meet the needs of modern users.

Android, the strength of accessibility

The attraction ofAndroid comes from its ability to offer a versatile operating system accessible on a variety of devices, its openness and compatibility with many mobile devices has allowed Android to maintain a significant market share over the years.

Windows, the underestimated potential

The mobile operating system Windows has a smaller market share compared to iOS and Android. However, let’s not forget its capabilities, in particular its fluid integration with the Microsoft ecosystem, which could well allow it to surprise in the future.

Security and voice assistants, the new fronts of competition

The year 2024 also saw the advent of new trends, of which security and artificial intelligence are the highlights. Likewise, the voice assistants have established themselves as a new axis of competition between these technological giants, opening a new path towards the future of the human-machine interface.

Factors influencing the market shares of iOS, Android and Windows

The mobile operating system market is multifactorial and constantly evolving. The market share between iOS, Android and Windows is largely influenced by several factors, including technological innovation, accessibility, AI integration, consumer preferences, L’application ecosystem, the price, among others.

Market share forecasts in 2024: iOS

Apple’s iOS has always been a leader in innovation and design. However, despite high-quality products, the high price of Apple devices is likely to hamper its growth in emerging markets. On the other hand, optimized AI integration could boost Apple’s market share.

Market share forecasts in 2024: Android

Android, due to its flexibility and accessibility, currently has a large market share. The variety of Android devices available at various prices has promoted its acceptance worldwide. This could be a long-term benefit for Google, but greater fragmentation could be both a blessing and a curse.

Market share forecasts in 2024: Windows

Windows Mobile has long been an underdog in the operating system wars. However, Microsoft is investing heavily in research and development to regain its share of the pie. With good AI integration and an improved application ecosystem, Windows could surprise in 2024.

It is clear that the mobile operating system market will continue to evolve and adapt to new technologies and consumer preferences. It’s a delicate balancing act between continuous innovation, understanding consumers and adapting to market dynamics. Either way, it looks like 2024 will be another exciting year for the world of mobile operating systems.

The usage share of an operating system is the percentage of computers running that operating system (OS). These statistics are estimates as wide scale OS usage data is difficult to obtain and measure. Reliable primary sources are limited and data collection methodology is not formally agreed. Currently devices connected to the internet allow for web data collection to approximately measure OS usage.

As of March 2025, Android, which uses the Linux kernel, is the world’s most popular operating system with 46% of the global market, followed by Windows with 25%, iOS with 18%, macOS with 6%, and other operating systems with 5% .[1] This is for all device types excluding embedded devices.

- For smartphones and other mobile devices, Android has 72% market share, and Apple’s iOS has 28%.[2]

- For desktop computers and laptops, Microsoft Windows has 71%, followed by Apple’s macOS at 16%, unknown operating systems at 8%, desktop Linux at 4%, then Google’s ChromeOS at 2%.[3][4]

- For tablets, Apple’s iPadOS (a variant of iOS) has 52% share and Android has 48% worldwide.[5]

- For the top 500 most powerful supercomputers, Linux distributions have had 100% of the marketshare since 2017.

- The global server operating system marketshare has Linux leading with a 62.7% marketshare, followed by Windows, Unix and other operating systems.[6]

Linux is also most used for web servers, and the most common Linux distribution is Ubuntu, followed by Debian. Linux has almost caught up with the second-most popular (desktop) OS, macOS, in some regions, such as in South America,[7] and in Asia it’s at 6.4% (7% with ChromeOS) vs 9.7% for macOS.[8] In the US, ChromeOS is third at 5.5%, followed by (desktop) Linux at 4.3%, but can arguably be combined into a single number 9.8%.[9][10]

The most numerous type of device with an operating system are embedded systems. Not all embedded systems have operating systems, instead running their application code on the «bare metal»; of those that do have operating systems, a high percentage are standalone or do not have a web browser, which makes their usage share difficult to measure. Some operating systems used in embedded systems are more widely used than some of those mentioned above; for example, modern Intel microprocessors contain an embedded management processor running a version of the Minix operating system.[11]

Worldwide device shipments

[edit]

|

|

This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: Some stats have not been updated in nearly a decade.. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (November 2024) |

According to Gartner, the following is the worldwide device shipments (referring to wholesale) by operating system, which includes smartphones, tablets, laptops and PCs together.

Worldwide device shipments by Operating System

| Source | Year | Android | iOS/macOS | Windows | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gartner[13] | 2019 (2.161 bln) | ||||

| Gartner[14] | 2017 (2.278 bln) | ||||

| Gartner[15] | 2016 (2.332 bln) | 10.63% (248 mln) | 11.2% (260 mln) | ||

| Gartner[12] | 2015 (2.4 bln) | 54.16% (1.3 bln) | 12.37% (297 mln)

macOS = 1% |

11.79% (283 mln) | 21.66% |

| Gartner[16] | 2014 | 48.61% | 11.04% | 14.0% | 26.34% |

| Gartner[17] | 2013 | 38.51% | 10.12% | 13.98% | 37.41% |

| Gartner[18] | 2012 | 22.8% | 9.6% | 15.62% | 51.98% |

Shipments (to stores) do not necessarily translate to sales to consumers, therefore suggesting the numbers indicate popularity and/or usage could be misleading. Not only do smartphones sell in higher numbers than PCs, but also a lot more by dollar value, with the gap only projected to widen, to well over double.[19]

On 27 January 2016, Paul Thurrott summarized the operating system market, the day after Apple announced «one billion devices»:

Apple’s «active installed base» is now one billion devices. [..] Granted, some of those Apple devices were probably sold into the marketplace years ago. But that 1 billion figure can and should be compared to the numbers Microsoft touts for Windows 10 (200 million, most recently) or Windows more generally (1.5 billion active users, a number that hasn’t moved, magically, in years), and that Google touts for Android (over 1.4 billion, as of September).

My understanding of iOS is that the user base was previously thought to be around 800 million strong, and when you factor out Macs and other non-iOS Apple devices, that’s probably about right. But as you can see, there are three big personal computing platforms.— Paul Thurrott[20]

For 2015 (and earlier), Gartner reports for «the year, worldwide PC shipments declined for the fourth consecutive year, which started in 2012 with the launch of tablets» with an 8% decline in PC sales for 2015 (not including cumulative decline in sales over the previous years).[21]

Microsoft backed away from their goal of one billion Windows 10 devices in three years (or «by the middle of 2018»)[22] and reported on 26 September 2016 that Windows 10 was running on over 400 million devices,[23] and in March 2019 on more than 800 million.[24]

In May 2020, Gartner predicted further decline in all market segments for 2020 due to COVID-19, predicting a decline of 13.6% for all devices. while the «Work from Home Trend Saved PC Market from Collapse», with only a decline of 10.5% predicted for PCs. However, in the end, according to Gartner, PC shipments grew 10.7% in the fourth quarter of 2020 and reached 275 million units in 2020, a 4.8% increase from 2019 and the highest growth in ten years.» Apple in 4th place for PCs had the largest growth in shipments for a company in Q4 of 31.3%, while «the fourth quarter of 2020 was another remarkable period of growth for Chromebooks, with shipments increasing around 200% year over year to reach 11.7 million units. In 2020, Chromebook shipments increased over 80% to total nearly 30 million units, largely due to demand from the North American education market.» Chromebooks sold more (30 million) than Apple’s Macs worldwide (22.5 million) in pandemic year 2020.[25]

According to the Catalyst group, the year 2021 had record high PC shipments with total shipments of 341 million units (including Chromebooks), 15% higher than 2020 and 27% higher than 2019, while being the largest shipment total since 2012.[26]

According to Gartner, worldwide PC shipments declined by 16.2% in 2022, the largest annual decrease since the mid-1990s, due to geopolitical, economic, and supply chain challenges. [27]

Tablet computers shipments

[edit]

In 2015, eMarketer estimated at the beginning of the year that the tablet installed base would hit one billion[28] for the first time (with China’s use at 328 million, which Google Play doesn’t serve or track, and the United States’s use second at 156 million). At the end of the year, because of cheap tablets – not counted by all analysts – that goal was met (even excluding cumulative sales of previous years) as:

Sales quintupled to an expected 1 billion units worldwide this year, from 216 million units in 2014, according to projections from the Envisioneering Group.

While that number is far higher than the 200-plus million units globally projected by research firms IDC, Gartner and Forrester, Envisioneering analyst Richard Doherty says the rival estimates miss all the cheap Asian knockoff tablets that have been churning off assembly lines.[..]

Forrester says its definition of tablets «is relatively narrow» while IDC says it includes some tablets by Amazon — but not all.[..]

The top tech purchase of the year continued to be the smartphone, with an expected 1.5 billion sold worldwide, according to projections from researcher IDC. Last year saw some 1.2 billion sold.[..]

Computers didn’t fare as well, despite the introduction of Microsoft’s latest software upgrade, Windows 10, and the expected but not realized bump it would provide for consumers looking to skip the upgrade and just get a new computer instead.

Some 281 million PCs were expected to be sold, according to IDC, down from 308 million in 2014. Folks tend to be happy with the older computers and keep them for longer, as more of our daily computing activities have moved to the smartphone.[..]

While Windows 10 got good reviews from tech critics, only 11% of the 1-billion-plus Windows user base opted to do the upgrade, according to Microsoft. This suggests Microsoft has a ways to go before the software gets «hit» status. Apple’s new operating system El Capitan has been downloaded by 25% of Apple’s user base, according to Apple.

This conflicts with statistics from IDC that say the tablet market contracted by 10% in 2015 with only Huawei, ranked fifth, with big gains, more than doubling their share; for fourth quarter 2015, the five biggest vendors were the same except that Amazon Fire tablets ranked third worldwide, new on the list, enabled by its not quite tripling of market share to 7.9%, with its Fire OS Android-derivative.[30]

Global tablet shipments[a]

| Source | Year | Android | iOS | Windows | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strategy Analytics[31] | Q2 2022 | 49% | 38% | 11% | 2% |

| Statista[32] | 2020 | 59.4% | 29.8% | 10.21% | 0.59% |

| Strategy Analytics[33] | 2015 | 68% | 22% | 10% | <0.1% |

| Gartner[34] | 2013 | 61.9% | 36.0% | 2.1% | <0.1% |

| Gartner[34] | 2012 | 45.8% | 52.8% | 1.0% | 0.3% |

Gartner excludes some devices from their tablet shipment statistic and includes them in a different category called «premium ultramobiles» with screen sizes of more than 10″ inches.[35]

Smartphone shipments

[edit]

There are more mobile phone owners than toothbrush owners,[36] with mobile phones the fastest growing technology in history.[citation needed] There are a billion more active mobile phones in the world than people (and many more than 10 billion sold so far with less than half still in use), explained by the fact that some people have more than one, such as an extra for work.[37] All the phones have an operating system, but only a fraction of them are smartphones with an OS capable of running modern applications. In 2018, 3.1 billion smartphones and tablets were in use across the world (with tablets, a small fraction of the total, generally running the same operating systems, Android or iOS, the latter being more popular on tablets. In 2019, a variant of iOS called iPadOS built for iPad tablets was released).

On 28 May 2015, Google announced that there were 1.4 billion Android users and 1 billion Google play users active during that month.[38][39] This changed to 2 billion monthly active users in May 2017.[40][41]

By late 2016, Android had been said to be «killing» Apple’s iOS market share (i.e. its declining sales of smartphones, not just relatively but also by number of units, when the whole market was increasing).[42] Gartner’s press release stated: «Apple continued its downward trend with a decline of 7.7 percent in the second quarter of 2016»,[43] which is their decline, based on absolute number of units, that underestimates the relative decline (with the market increasing), along with the misleading «1.7 percent [point]» decline. That point decline means an 11.6% relative decline (from 14.6% down to 12.9%).

Although by units sold Apple was declining in the late 2010s, the company was almost the only vendor making any profit in the smartphone sector from hardware sales alone. In Q3 2016 for example, they captured 103.6% of the market profits.[44]

In May 2019 the biggest smartphone companies (by market share) were Samsung, Huawei and Apple, respectively.[45]

In November 2024, a new competitor to Android and iOS emerged, when sales of the Huawei Mate 70 started with the all-new operating system HarmonyOS NEXT installed[46] on the flagship device. Future Huawei devices are to be sold mainly with this operating system, creating a third player on the market for smartphone operating systems.[47]

The following table shows worldwide smartphone sales to end users by operating systems, as measured by Gartner, International Data Corporation (IDG) and others:

Smartphone shipments by OS from 2017 (Windows and BlackBerry no longer measurable)

| Source | Method | Year/quarter | Android (including forks) |

HarmonyOS[48] | iOS | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Counterpoint[49] | Units sold per quarter | 2024 Q4 | 74% | 4% | 22% | 0% |

| Gartner[50] | Units sold in quarter | 2018 Q1 | 85.9% | — | 14.1% | 0.0% |

| Gartner[51] | Units sold per year | 2017 | 85.9% | — | 14.0% | 0.1% |

| Gartner[52] | Units sold in quarter | 2017 Q1 | 86.1% | — | 13.7% | 0.2% |

Smartphone shipments by OS until 2016

| Source | Method | Year/quarter | Android (including forks) |

BlackBerry (all versions) |

iOS | Symbian | Windows (all versions) |

Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gartner[53] | Units sold per year | 2016 | 84.8% | — | 14.4% | — | — | 0.8% |

| Gartner[54] | Units sold in quarter | 2016 Q4 | 81.7% | 0.0% | 17.9% | — | 0.3% | 0.1% |

| Gartner[55] | Units sold in quarter | 2016 Q3 | 87.8% | 0.1% | 11.5% | — | 0.4% | 0.2% |

| Gartner[56] | Units sold in quarter | 2016 Q2 | 86.2% | 0.1% | 12.9% | — | 0.6% | 0.2% |

| Gartner[57] | Units sold in quarter | 2016 Q1 | 84.1% | 0.2% | 14.8% | — | 0.7% | 0.2% |

| Gartner[58] | Units sold in quarter | 2015 Q4 | 80.7% | 0.2% | 17.7% | — | 1.1% | 0.2% |

| Gartner[59] | Units sold in quarter | 2015 Q2 | 82.2% | 0.3% | 14.6% | — | 2.5% | 0.4% |

| Gartner[60] | Units sold in quarter | 2014 Q4 | 76.0% | 0.5% | 20.4% | — | 2.8% | 0.4% |

| Strategy Analytics[61] | Units shipped in quarter | 2014 Q3 | 81.3% | 1.0% | 13.4% | — | 4.1% | 0.2% |

| Gartner[62] | Units sold in quarter | 2014 Q2 | 83.8% | 0.7% | 12.2% | — | 2.8% | 0.5% |

| Gartner[63] | Units sold in quarter | 2013 Q2 | 79.0% | 2.7% | 14.2% | 0.3% | 3.3% | 0.6% |

| Gartner[64] | Units sold in quarter | 2013 Q1 | 74.4% | 3.0% | 18.2% | 0.6% | 2.9% | 1.0% |

| International Data Corporation[65] | Units shipped in quarter | 2013 Q1 | 75.0% | 2.9% | 17.3% | 0.6% | 3.2% | 0.0% |

|

|

This section needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. |

| Web clients’ OS family statistics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Android | 45.49% | |

| Windows | 25.35% | |

| iOS | 18.26% | |

| macOS | 5.67% | |

| Unknown | 2.97% | |

| Linux | 1.38% | |

| Web clients’ OS family market share according to StatCounter for February 2025.[66] The information on web clients is obtained from user agent information obtained through JavaScript code run by web browsers supplied to web servers. «Unknown» is probably mostly Windows operating systems.[citation needed] These figures have a large margin of error for a variety of reasons. For a discussion on the shortcomings see usage share of web browsers. |

Data from various sources published over the 2021/2022 period is summarized in the table below. All of these sources monitor a substantial number of websites, any statistics that relate to only one web site have been excluded.

Android currently ranks highest,[67] above Windows (incl. Xbox console) systems. Windows Phone accounted for 0.51% of the web usage, before it was discontinued.[68]

Considering all personal computers, Microsoft Windows is well below 50% usage share on every continent, and at 30% in the US (24% single-day low) and in many countries lower, e.g. China, and in India at 19% (12% some days) and Windows’ lowest share globally was 29% in May 2022 (25% some days), and 29% in the US.[69]

For a short time, iOS was slightly more popular than Windows in the US, but this is no longer the case. Worldwide, Android holds 45.49%, more than Windows at 25.35%, and iOS third at 18.26%.

In Africa, Android is at 66.07%, Windows is 13.46 (and iOS third at 10.24%).[70]

Before iOS became the most popular operating system in any independent country, it was most popular in Guam, an unincorporated territory of the United States, for four consecutive quarters in 2017–18,[71][72] although Android is now the most popular there.[73] iOS has been the highest ranked OS in Jersey (a British Crown dependency in Europe) for years, by a wide margin, and iOS was also highest ranked in Falkland Islands, a British Overseas Territory, for one quarter in 2019, before being overtaken by Android in the following quarter.[74][75] iOS is competitive with Windows in Sweden, where some days it is more used.[76]

The designation of an «Unknown» operating system is strangely high in a few countries such as Madagascar where it was at 32.44% (no longer near as high).[77] This may be due to the fact that StatCounter uses browser detection to get OS statistics, and there the most common browsers are not often used. The version breakdown for browsers in Madagascar shows «Other» at 34.9%,[78] and Opera Mini 4.4 is the most popular known browser at 22.1% (plus e.g. 3.34% for Opera 7.6). However browser statistics without version-breakdown has Opera at 48.11% with the «Other» category very small.[79][clarification needed]

In China, Android became the highest ranked operating system in July 2016 (Windows has occasionally topped it since then, while since April 2016 it or all non-mobile operating systems haven’t outranked mobile operating systems, meaning Android plus iOS).[80] In the Asian continent as a whole, Android has been ranked highest since February 2016 and Android alone has the majority share,[81] because of a large majority in all the most populous countries of the continent, up to 84% in Bangladesh, where it has had over 70% share for over four years.[82] Since August 2015, Android is ranked first, at 48.36% in May 2016, in the African continent – when it took a big jump ahead of Windows 7,[83] and thereby Africa joined Asia as a mobile-majority continent. China is no longer a desktop-majority country,[84] joining India, which has a mobile-majority of 71%, confirming Asia’s significant mobile-majority.

Online usage of Linux kernel derivatives (Android + ChromeOS + other Linux) exceeds that of Windows. This has been true since some time between January and April 2016, according to W3Counter[85] and StatCounter.[86]

However, even before that, the figure for all Unix-like OSes, including those from Apple, was higher than that for Windows.

| Source | Date | Microsoft Windows (kernel): | Apple Darwin: |

Linux kernel: | Others:[b] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 8/8.1 | 7 | Vista | XP | WP&RT | Other | macOS | iOS | Linux | Android | Other | |||

| W3Counter[87] | Feb 2025 | 20.95% | 4.45% | 11.71% | 2.56% | 43.09% | — | |||||||

| W3Counter[88] | Oct 2022 | 19.23% | — | 3.4% | — | — | — | — | 4.03% | 19.23% | — | 45.18% | — | — |

| W3Counter[89] | Oct

2020 |

20.55% |

— |

6.74% |

— | — | — | — |

8.06% |

13.67% |

— |

37.44% |

— | — |

| W3Counter[90] | Jun 2019 | 16.23% | N/A | 14.32% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 3.58% | 13.54 | N/A | 38.76% | N/A | N/A |

| W3Counter[90] | Jun 2018 | 11.14 | N/A | 12.29% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2.80% | 10.68% | N/A | 53.21% | — | N/A |

| W3Counter[91] | Dec 2016 | 13.79 | 4.54% | 18.45% | N/A | N/A | — | N/A | 4.45% | 12.60% | 3.8% | 34.37% | — | 8% |

| StatCounter Global Stats[92] | Mar 2017 | 12.98% | 4.57% | 17.84% | 0.41% | 2.07% | 0% | 0.06% | 5.17% | 13.09% | 0.75% | 37.93% | 0.76% | 7.21% |

| StatCounter Global Stats[92] | Dec 2016 | 12.5% | 4.79% | 18% | 0.46% | 2.24% | 0.64% | 0.09% | 4.92% | 12.71% | 0.86% | 37.8% | 0.72% | 4.61% |

| StatCounter Global Stats[93] | Oct 2016 | 12.08% | 5.21% | 18.97% | 0.6% | 2.44% | 0.7% | 0.05% | 5.3% | 12.04% | 0.85% | 34.46% | 0.63% | 6.67% |

| StatCounter Global Stats[94] | May 2016 | 10.27% | 6.68% | 22.25% | 0.73% | 3.44% | 0.83% | 0.8% | 5.05% | 11.38% | 0.91% | 31.6% | 0.64% | 6.15% |

| StatCounter Global Stats[94] | Dec 2015 | 6.67% | 8.5% | 26.66% | 1.0% | 4.75% | 0.92% | 0.2% | 5.51% | 10.82% | 1.03% | 27.01% | 0.36% | 6.57% |

| Wikimedia[95] | Dec 2016 | 14.0% | 4.65% | 18.0% | 0.43% | 1.70% | 0.93% | 0.50% | 5.4% | 19.0% | 0.80% | 23.0% | 0.30% | 11.29% |

Desktop and laptop computers

[edit]

|

|

This section needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. |

Windows is still the dominant desktop OS, but the dominance varies by region and it has gradually lost market share to other desktop operating systems (not just to mobile) with the slide very noticeable in the US, where macOS usage has more than quadrupled from Jan. 2009 to Dec. 2020 to 30.62% (i.e. in Christmas month; and 34.72% in April 2020 in the middle of COVID-19, and iOS was more popular overall that year;[97] globally Windows lost to Android that year,[98] as for the two years prior), with Windows down to 61.136% and ChromeOS at 5.46%, plus traditional Linux at 1.73%.[99]

There is little openly published information on the device shipments of desktop and laptop computers. Gartner publishes estimates, but the way the estimates are calculated is not openly published. Another source of market share of various operating systems is StatCounter[100] basing its estimate on web use (although this may not be very accurate). Also, sales may overstate usage. Most computers are sold with a pre-installed operating system, with some users replacing that OS with a different one due to personal preference, or installing another OS alongside it and using both. Conversely, sales underestimate usage by not counting unauthorized copies. For example, in 2009, approximately 80% of software sold in China consisted of illegitimate copies.[101] In 2007, the statistics from an automated update of IE7 for registered Windows computers differed with the observed web browser share, leading one writer to estimate that 25–35% of all Windows XP installations were unlicensed.[102]

The usage share of Microsoft’s (then latest operating system version) Windows 10 has slowly increased since July/August 2016, reaching around 27.15% (of all Windows versions, not all desktop or all operating systems) in December 2016. It eventually reached 79.79% on 5 October 2021, the same day on which its successor Windows 11 was released. In the United States, usage of Windows XP has dropped to 0.38% (of all Windows versions), and its global average to 0.59%, while in Africa it is still at 2.71%, and in Armenia it is more than 70%, as of 2017.[103]

StatCounter web usage data of desktop or laptop operating systems varies significantly by country. For example, in 2017, macOS usage in North America was at 16.82%[104] (17.52% in the US[105]) whereas in Asia it was only 4.4%.[106] As of July 2023, macOS usage has increased to 30.81% in North America[107] (31.77% in the US)[108] and to 9.64% in Asia.[109]

Since mid-2020, the world uses smartphones more than desktop (including laptop) computers.[110][111][112] For global statistics it’s every day of the week. It has also happened for all individual continents[113][114][115] (at least for some weeks, and also for the United States where the smartphone share reached 54.26% in July 2022,[116][117][118][119] and also that high in 2021). The proportions do vary widely by region (more so than by the day), e.g. in Africa the smartphone share is highest at 72%, in Asia at 69% and in South America at 60%, in Europe is 49% while desktop is slightly lower, and in the United States it’s at 43% and desktop at 54% (previously at 50%). On some continents, e.g. North America and the US, smartphone use may only go over 50% on weekends, since smartphones usage increases on weekends,[120][121][122][123] while the smartphone share has gone up to 54% for a single day (Thanksgiving), and on average over 50% for full week.[124][125]

- Smartphones (58.01%)

- Desktops/Laptops (39.49%)

- Tablets (2.46%)

- Console (0.06%)

The 2023 Stack Overflow developer survey counts 87,222 survey responses. However, usage of a particular system as a desktop or as a server was not differentiated in the survey responses. The operating system share among those identifying as professional developers was:[126]

- Windows: 46.91%

- macOS: 33%

- Ubuntu: 26.69%

- BSD: 0.59%

Microsoft data on Windows usage

In June 2016, Microsoft claimed Windows 10 had half the market share of all Windows installations in the US and UK, as quoted by BetaNews:

Microsoft’s Windows trends page [shows] Windows 10 hit 50 percent in the US (51 percent in the UK, 39 percent globally), while … Windows 7 was on 38 percent (36 percent in the UK, 46 percent globally).

A big reason for the difference in numbers comes down to how they are recorded. … actual OS usage (based on web browsing), while Microsoft records the number of devices Windows 10 is installed on. … Microsoft also only records Windows 7, Windows 8, Windows 8.1 and Windows 10, while NetMarketShare includes both XP and Vista.— BetaNews[127]

Desktop computer games

[edit]

The digital video game distribution platform Steam publishes a monthly «Hardware & Software Survey», with the statistics below:

| Month | Microsoft Windows | Mac OS | Linux | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| December 2023[128] | 96.40% | 1.63% | 1.97% | |

| December 2022[129] | 96.15% | 2.48% | 1.38% | |

| December 2021 | 96.19% | 2.70% | 1.11% | |

| December 2020[129] | 96.41% | 2.82% | 0.78% | |

| December 2019[130] | 96.89% | 2.47% | 0.67% | |

| January 2019[131] | 95.92% | 3.27% | 0.82% | |

| January 2018[132] | 97.76% | 1.84% | 0.41% | |

| January 2017[133] | 95.79% | 3.31% | 0.80%† | |

| January 2016[134] | 95.39% | 3.55% | 0.95% | |

| January 2015[135] | 95.48% | 3.32% | 1.09% | |

| January 2014[136] | 94.93% | 3.47% | 0.86% | 0.74% |

^† These figures, as reported by Steam, do not include SteamOS statistics.[137]

Smartphones OS by usage

[edit]

By Q1 2018, mobile operating systems on smartphones included Google’s dominant Android (and variants) and Apple’s iOS which combined had an almost 100% market share.[138]

Smartphone penetration vs. desktop use differs substantially by country. Some countries, like Russia, still have smartphone use as low as 22.35% (as a fraction of all web use),[139] but in most western countries, smartphone use is close to 50% of all web use. This doesn’t mean that only half of the population has a smartphone, could mean almost all have, just that other platforms have about equal use. Smartphone usage share in developing countries is much higher – in Bangladesh, for example, Android smartphones had up to 84% and currently 70% share,[82] and in Mali smartphones had over 90% (up to 95%) share for almost two years.[140][141] (A section below has more information on regional trends on the move to smartphones.)

There is a clear correlation between the GDP per capita of a country and that country’s respective smartphone OS market share, with users in the richest countries being much more likely to choose Apple’s iPhone, with Google’s Android being predominant elsewhere.[142][143][144]

Global mobile OS web usage[c]

| Source | Method | Quarter/month | Android (including forks) |

iOS | Windows (all versions) |

BlackBerry (all versions) |

Symbian | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statista[145] | based on page views per month worldwide | 2022 Q4 | 71.1% | 28.3% | — | — | — | 0.6% |

| StatCounter Global Stats[146] | Browsing (page view) | 2021, Oct | 71.09% | 28.21% | 0.01% | — | — | 0.69% |

| StatCounter Global Stats[147] | Browsing (page view) | 2020, Oct | 72.93% | 26.53% | 0.03% | — | — | 0.51% |

| StatCounter Global Stats | Browsing (page view) | 2019, Sep | 76.24% | 22.48% | 0.17% | 0.02% | 0.02% | 1.07% |

| StatCounter Global Stats[148] | Browsing (page view) | 2015, Mar | 61.94% | 22.64% | 2.27% | NA | 6.00% | 7.09% |

| StatCounter Global Stats[148] | Browsing (page view) | 2014, Aug | 54.87% | 23.57% | 2.36% | 1.59% | 9.73% | 7.87% |

| StatCounter Global Stats[148] | Browsing (page view) | 2014, Feb | 47.57% | 22.97% | 2.22% | 2.62% | 14.86% | 6.08% |

| Wikimedia (includes tablets)[d] | Browsing (page view) | 2013, Mar | 25.93% | 66.53% | 1.85% | 2.02% | 3.03% | 1.12% |

United States mobile OS web usage

| Source | Method | Quarter/month | Android (including forks) |

iOS | Windows (all versions) |

BlackBerry (all versions) |

Symbian | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| comScore[149] (US only) | US subscribers | 2017, Jan | 52.0% | 43.9% | 1.5% | 0.5% | — | — |

| comScore[150] (US only) | US subscribers | 2016, Jan | 52.8% | 43.6% | 2.7% | 0.8% | — | — |

| comScore[151] (US only) | US subscribers | 2015, Jan | 53.2% | 41.3% | 3.6% | 1.8% | 0.1% | N/A |

| comScore[152] (US only) | US subscribers | 2014, Jan | 51.7% | 41.6% | 3.2% | 3.1% | 0.2% | N/A |

| comScore[153] (US only) | US subscribers | 2012, Feb | 50.1% | 30.2% | 3.9% | 13.4% | 1.5% | — |

| comScore[154] (US only) | US subscribers | 2010, Dec | 28.7% | 25.0% | 8.4% | 31.6% | — | 3.7% |

Tablet computers OS by usage

[edit]

|

|

This section needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. |

Tablet computers, or simply tablets, became a significant OS market share category starting with Apple’s iPad. In Q1 2018, iOS had 65.03% market share and Android had 34.58% market share.[155] Windows tablets may not get classified as such by some analysts, and thus barely register; e.g. 2-in-1 PCs may get classified as «desktops», not tablets.

Since 2016, in South America (and Cuba[156] in North America), Android tablets have gained majority,[157] and in Asia in 2017 Android was slightly more popular than the iPad, which was at 49.05% usage share in October 2015.[158][159][160] In Africa, Android tablets are much more popular while elsewhere the iPad has a safe margin.

As of March 2015, Android has made steady gains to becoming the most popular tablet operating system:[161] that is the trend in many countries, having already gained the majority in large countries (India at 63.25%,[162] and in Indonesia at 62.22%[163]) and in the African continent with Android at 62.22% (first to gain Android majority in late 2014),[164] with steady gains from 20.98% in August 2012[165] (Egypt at 62.37%,[166] Zimbabwe at 62.04%[166]), and South America at 51.09% in July 2015.[167] (Peru at 52.96%[168]). Asia is at 46%.[169] In Nepal, Android gained majority lead in November 2014 but lost it down to 41.35% with iOS at 56.51%.[170] In Taiwan, as of October 2016, Android after having gained a confident majority, has been on a losing streak.[171] China is a major exception to Android gaining market share in Asia (there Android phablets are much more popular than Android tablets, while similar devices get classified as smartphones) where the iPad/iOS is at 82.84% in March 2015.[172]

Global tablet web usage

| Source | Month | iOS/iPadOS | Android | Windows | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| StatCounter[173] | Aug 2023 | 54.68% | 45.11% | 0.02% | 0.07% |

| StatCounter[174] | Oct 2020 | 58.86% | 41.02% | 0.08% | 0.04% |

| StatCounter[175] | Dec 2019 | 63.11% | 36.65% | 0.15% | 0.09% |

| StatCounter[176] | Jul 2018 | 65.03% | 34.58% | 0.21% | 0.18% |

| StatCounter[177] | Jul 2015 | 65.51% | 31.36% | 0.78% | 2.93% |

| StatCounter[178] | Feb 2015 | 66.47% | 29.6% | 1.16% | 2.73% |

| StatCounter[179] | Oct 2014 | 71.67% | 25.62% | 0.08% | 2.63% |

|

|

This section needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. |

According to StatCounter web use statistics (a proxy for all use), smartphones are more popular than desktop computers globally (and Android in particular more popular than Windows). Including tablets with mobiles/smartphones, as they also run so-called mobile operating systems, even in the United States (and most countries) are mobiles including tablets more popular than other (older originally made for desktops) operating systems (such as Windows and macOS). Windows in the US (at 33.42%) has only 8% head-start (2.55-percentage points) over iOS only; with Android, that mobile operating system and iOS have 52.14% majority.[180] Alternatively, Apple, with iOS plus their non-mobile macOS (9.33%) has 20% more share (6.7-percentage points more) than Microsoft’s Windows in the country where both companies were built.

Although desktop computers are still popular in many countries (while overall down to 44.9% in the first quarter of 2017[181]), smartphones are more popular even in many developed countries. A few countries on all continents are desktop-minority with Android more popular than Windows; many, e.g. Poland in Europe, and about half of the countries in South America, and many in North America, e.g. Guatemala, Honduras, Haiti; up to most countries in Asia and Africa[182] with smartphone-majority because of Android, Poland and Turkey in Europe highest with 57.68% and 62.33%, respectively. In Ireland, smartphone use at 45.55% outnumbers desktop use and mobile as a whole gains majority when including the tablet share at 9.12%.[183][184] Spain was also slightly desktop-minority. As of July 2019, Sweden had been desktop-minority for eight weeks in a row.[185]

The range of measured mobile web use varies a lot by country, and a StatCounter press release recognizes «India amongst world leaders in use of mobile to surf the internet»[186] (of the big countries) where the share is around (or over) 80%[187] and desktop is at 19.56%, with Russia trailing with 17.8% mobile use (and desktop the rest).

Smartphones (discounting tablets), first gained majority in December 2016 (desktop-majority was lost the month before),[where?] and it wasn’t a Christmas-time fluke, as while close to majority after smartphone majority happened again in March 2017.[188][clarification needed]

In the week of 7–13 November 2016, smartphones alone (without tablets) overtook desktop for the first time, albeit for a short period.[189] Examples of mobile-majority countries include Paraguay in South America, Poland in Europe and Turkey and most of Asia and Africa. Some of the world is still desktop-majority, with for example the United States at 54.89% (but not on all days).[190] However, in some territories of the United States, such as Puerto Rico,[191] desktop is significantly under majority, with Windows just under 25%, overtaken by Android.

On 22 October 2016 (and subsequent weekends), mobile showed majority.[192] Since 27 October, the desktop hasn’t had a majority, including on weekdays. Smartphones alone have shown majority since 23 December to the end of the year, with the share topping at 58.22% on Christmas Day.[193] To the «mobile»-majority share of smartphones, tablets could be added giving a 63.22% majority. While an unusually high top, a similar high also occurred on Monday 17 April 2017, with the smartphone share slightly lower and tablet share slightly higher, combining to 62.88%.

Formerly, according to a StatCounter press release, the world has turned desktop-minority;[194] as of October 2016, at about 49% desktop use for that month, but mobile wasn’t ranked higher, tablet share had to be added to it to exceed desktop share.

For the Christmas season (i.e. temporarily, while desktop-minority remains and smartphone-majority on weekends[195][196]), the last two weeks in December 2016, Australia (and Oceania in general)[197] was desktop-minority for the first time for an extended period, i.e. every day from 23 December.[198]

In South America, smartphones alone took majority from desktops on Christmas Day,[196] but for a full-week-average, desktop is still at least at 58%.[199]

The UK desktop-minority dropped down to 44.02% on Christmas Day and for the eight days to the end of the year.[200] Ireland joined some other European countries with smartphone-majority, for three days after Christmas, topping that day at 55.39%.[201][202]

In the US, desktop-minority happened for three days on and around Christmas (while a longer four-day stretch happened in November, and happens frequently on weekends).[203]

According to StatCounter web use statistics (a proxy for all use), in the week from 7–13 November 2016, «mobile» (meaning smartphones) alone (without tablets) overtook desktop, for the first time, with them highest ranked at 52.13% (on 27 November 2016)[204] or up to 49.02% for a full week.[205][206] Mobile-majority applies to countries such as Paraguay in South America, Poland in Europe and Turkey; and the continents Asia and Africa. Large regions of the rest of the world are still desktop-majority, while on some days, the United States,[207] (and North America as a whole)[208] isn’t; the US is desktop-minority up to four days in a row,[209] and up to a five-day average.[210] Other examples, of desktop-minority on some days, include the UK,[208] Ireland,[211] Australia[212] (and Oceania as a whole); in fact, at least one country on every continent[213][214][215] has turned desktop-minority (for at least a month). On 22 October 2016 (and subsequent weekends), mobile has shown majority.[216]

Previously, according to a StatCounter press release, the world has turned desktop-minority;[217] as of October 2016, at about 49% desktop use for that month,[218][219] with desktop-minority stretching up to an 18-weeks/4-months period from 28 June to 31 October 2016,[220][221] while whole of July, August or September 2016, showed desktop-majority (and many other long sub-periods in the long stretch showed desktop-minority; similarly only Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays are desktop-minority). The biggest continents, Asia and Africa, have shown vast mobile-majority for long time (any day of the week), as well as several individual countries elsewhere have also turned mobile-majority: Poland, Albania (and Turkey)[222] in Europe and Paraguay and Bolivia[223] in South America.[224]

According to StatCounter’s web use statistics, Saturday 28 May 2016, was the day when smartphones («mobile» at StatCounter, that now counts tablets separately) became a most used platform, ranking first, at 47.27%, above desktops.[225][226] The next day, desktops slightly outnumbered «mobile» (unless counting tablets: some analysts count tablets with smartphones or separately while others with desktops – even when most tablets are iPad or Android, not Windows devices).[227]

Since Sunday 27 March 2016, the first day the world dipped to desktop-minority,[228] it has happened almost every week, and by week of 11–17 July 2016, the world was desktop-minority,[229] followed by the next week, and thereon also for a three-week period.[230] The trend is still stronger on weekends, with e.g. 17 July 2016 showed desktop at 44.67%, «mobile» at 49.5% plus tablets at 5.7%.[231] Recent weekly data shows a downward trend for desktops.[232][233]

According to StatCounter web use statistics (a proxy for overall use), on weekends desktops worldwide lose about 5 percent points, e.g. down to 51.46% on 15 August 2015, with the loss in (relative) web use going to mobile (and also a minuscule increase for tablets),[234] mostly because Windows 7, ranked 1st on workdays, declines in web use, with it shifting to Android and lesser degree to iOS.[235]

Two continents have already crossed over to mobile-majority (because of Android), based on StatCounters web use statistics. In June 2015, Asia became the first continent where mobile overtook desktop[236] (followed by Africa in August;[237] while Nigeria had mobile majority in October 2011,[238][239] because of Symbian – that later had 51% share, then Series 40 dominating, followed by Android as dominating operating system[240]) and as far back as October 2014, they had reported this trend on a large scale in a press release: «Mobile usage has already overtaken desktop in several countries including India, South Africa and Saudi Arabia».[241] In India, desktop went from majority, in July 2012, down to 32%.[242] In Bangladesh desktop went from majority, in May 2013, down to 17%, with Android alone now accounting for majority web use.[243] Only a few African countries were still desktop-majority[244] and many have a large mobile majority including Ethiopia and Kenya, where mobile usage is over 72%.[245]

The popularity of mobile use worldwide has been driven by the huge popularity increase of Android in Asian countries, where Android is the highest ranked operating system statistically in virtually every south-east Asian country,[246] while it also ranks most popular in almost every African country. Poland has been desktop-minority since April 2015,[247] because of Android being vastly more popular there,[248] and other European countries, such as Albania (and Turkey), have also crossed over. The South America continent is somewhat far from losing desktop-majority, but Paraguay had lost it as of March 2015.[249] Android and mobile browsing in general has also become hugely popular in all other continents where desktop has a large desktop base and the trend to mobile is not as clear as a fraction of the total web use.

While some analysts count tablets with desktops (as some of them run Windows), others count them with mobile phones (as the vast majority of tablets run so-called mobile operating systems, such as Android or iOS on the iPad). iPad has a clear lead globally, but has clearly lost the majority to Android in South America,[250] and a number of Eastern European countries such as Poland; lost virtually all African countries and has lost the majority twice in Asia, but gained the majority back (while many individual countries, e.g. India and most of the middle East have clear Android majority on tablets).[251] Android on tablets is thus second most popular after the iPad.[252]

In March 2015, for the first time in the US the number of mobile-only adult internet users exceeded the number of desktop-only internet users with 11.6% of the digital population only using mobile compared to 10.6% only using desktop; this also means the majority, 78%, use both desktop and mobile to access the internet.[253] A few smaller countries in North America, such as Haiti (because of Android) have gone mobile majority (mobile went to up to 72.35%, and is at 64.43% in February 2016).[254]

The region with the largest Android usage[67] also has the largest mobile revenue.[255]

Mobile app revenue (US$bn)

| 2020[256] | |

|---|---|

| Asia Pacific | $85.3B |

| North and South America | $74.5B |

| Europe, Middle East, and Africa | $29.1B |

Public servers on the Internet

[edit]

Internet based servers’ market share can be measured with statistical surveys of publicly accessible servers, such as web servers, mail servers[257] or DNS servers on the Internet: the operating systems powering such servers are found by inspecting raw response messages. This method gives insight only into market share of operating systems that are publicly accessible on the Internet.

There will be differences in the result depending on how the sample is done and observations weighted. Usually the surveys are not based on a random sample of all IP addresses, domain names, hosts or organisations, but on servers found by some other method.[citation needed] Additionally, many domains and IP addresses may be served by one host and some domains may be served by several hosts or by one host with several IP addresses.

| Source | Date | Unix, Unix-like | Microsoft Windows | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| W3Techs | 29 March 2025 | 88.8% | 11.4% | [258] |

| W3Techs | 14 July 2022 | 80.1% | 20.1% | [259][260] |

| Security Space | Feb 2014 | <79.3% | >20.7% | [261][262] |

|

- Note

- Revenue comparisons often include «operating system software, other bundled software»[264] and are not appropriate for usage comparison as the Linux operating system costs nothing (including «other bundled software»), except if optionally using commercial distributions such as Red Hat Enterprise Linux (in that case, cost of software for all software bundled with hardware has to be known for all operating systems involved, and subtracted). In cases where no-cost Linux is used, such comparisons underestimate Linux server popularity and overestimate other proprietary operating systems such as Unix and Windows.

Mainframes are larger and more powerful than most servers, but not supercomputers. They are used to process large sets of data, for example enterprise resource planning or credit card transactions.

The most common operating system for mainframes is IBM’s z/OS.[265][citation needed] Operating systems for IBM Z generation hardware include IBM’s proprietary z/OS,[266] Linux on IBM Z, z/TPF, z/VSE and z/VM.

Gartner reported on 23 December 2008 that Linux on System z was used on approximately 28% of the «customer z base» and that they expected this to increase to over 50% in the following five years.[267] Of Linux on IBM Z, Red Hat and Micro Focus compete to sell RHEL and SLES respectively:

- Prior to 2006, Novell claimed a market share of 85% or more for SUSE Linux Enterprise Server.

- Red Hat has since claimed 18.4% in 2007 and 37% in 2008.[268]

- Gartner reported at the end of 2008 that Novell’s SUSE Linux Enterprise Server had an 80% share of mainframe Linux.[267][dead link]

Like today’s trend of mobile devices from personal computers,[253] in 1984 for the first time estimated sales of desktop computers ($11.6 billion) exceeded mainframe computers ($11.4 billion). IBM received the vast majority of mainframe revenue.[269]

From 1991 to 1996, AT&T Corporation briefly owned NCR, one of the major original mainframe producers. During the same period, companies found that servers based on microcomputer designs could be deployed at a fraction of the acquisition price and offer local users much greater control over their own systems given the IT policies and practices at that time. Terminals used for interacting with mainframe systems were gradually replaced by personal computers. Consequently, demand plummeted and new mainframe installations were restricted mainly to financial services and government. In the early 1990s, there was a rough consensus among industry analysts that the mainframe was a dying market as mainframe platforms were increasingly replaced by personal computer networks.[270]

In 2012, NASA powered down its last mainframe, an IBM System z9.[271] However, IBM’s successor to the z9, the z10, led a New York Times reporter to state four years earlier that «mainframe technology—hardware, software and services—remains a large and lucrative business for IBM, and mainframes are still the back-office engines behind the world’s financial markets and much of global commerce».[272] As of 2010, while mainframe technology represented less than 3% of IBM’s revenues, it «continue[d] to play an outsized role in Big Blue’s results».[273]

The TOP500 project lists and ranks the 500 fastest supercomputers for which benchmark results are submitted. Since the early 1990s, the field of supercomputers has been dominated by Unix or Unix-like operating systems, and starting in 2017, every top 500 fastest supercomputer uses Linux as its supercomputer operating system.

The last supercomputer to rank #1 while using an operating system other than Linux was ASCI White, which ran AIX. It held the title from November 2000 to November 2001,[274] and was decommissioned in 2006. Then in June 2017, two AIX computers held rank 493 and 494,[275] the last non-Linux systems before they dropped off the list.

Historically all kinds of Unix operating systems dominated, and in the end ultimately Linux remains.

| Category | Source | Date | Linux | UNIX and Unix-like (not incl. Linux) | Windows | In‑house | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Desktop, laptop | StatCounter Global Stats[277] | June 2023 | Linux kernel family 7.23%: ChromeOS 4.15% (in the US up to 8.0%) plus traditional «Linux» 3.08% | 21.38% (macOS) | 68.15% (all versions) | 3.24% | |

| Embedded[e] | EE Times[278] | Mar 2019 | 38.42% (embedded Linux, Ubuntu, Android, other) | 2.82% (QNX, LynxOS) | 10.73% (Windows 10, Windows Embedded Compact) | 10.73% | 37.30% |

| Mainframe | Gartner[268] | Dec 2008 | 28% (SLES, RHEL) | 72% (z/OS)[f] | |||

| Server (web) | W3Techs[279] | Sep 2021 | Likely 77.4% (39.8% confirmed)[g] (Ubuntu, CentOS, Debian, Gentoo, RHEL, …)[280] | Less than 1% is confirmed to be UNIX or Unix-like and non-Linux. The top operating systems in order are: 0.3% BSD (97.8% of which is FreeBSD),[281] <0.1% Darwin,[282] <0.1% HP-UX,[283] <0.1% Solaris,[284] and <0.1% Minix.[285][g] | 22.7% (Windows Server 2019, WS2016, WS2012) Microsoft’s own webserver runs 6.6% of websites.[286] |

||

| Smartphone, tablet | StatCounter Global Stats[287] | Apr 2020 | 70.80% (Android, KaiOS) | 28.79% (iOS) | 0.07% | 0.34% | |

| Supercomputer | TOP500[288] | Nov 2019 | 100% (Custom) | ||||

| Supercomputer | TOP500[288] | Nov 2024 | 100% (Custom) |

- Comparison of operating systems

- List of operating systems

- Timeline of operating systems

- Usage share of web browsers

- Mobile OS market share

- ^ «Shipments refer to sell-in», that is, wholesale.

- ^ The ‘Others’ column is obtained by summing all percentage data and subtracting from 100%.

- ^ Table is only showing mobile OS market share – not the overall market share.

- ^ Wikimedia Foundation statistics consider tablets as part of the mobile OS market share.

- ^ Embedded is a vast category, which has subcategories that include automotive, avionics, health, medical equipment, consumer electronics, intelligent homes, and telecommunications. The aggregated information above may be very different for each subcategory taken separately.

- ^ z/OS’s UNIX environment coexists with its native environment, which dates back to OS/360.

- ^ a b «UNIX and Unix-like (including Linux)» represents 77.4% of the total web server/website market share however 48.2% of that market share does not show «more specifically» which operating system.

- ^ «Operating System Market Share Worldwide». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 9 March 2025.

- ^ «Mobile Operating System Market Share Worldwide». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 9 March 2025.

- ^ «Now more than ever, ChromeOS is Linux with Google’s desktop environment». About Chromebooks. 1 August 2023. Retrieved 25 September 2024.

- ^ «Desktop Operating System Market Share Worldwide». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 9 March 2025.

- ^ «Tablet Operating System Market Share Worldwide». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 9 March 2025.

- ^ «Server Operating System Market Volume». Fortune Business Insights. Retrieved 15 November 2024.

- ^ «Desktop Operating System Market Share South America». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ «Desktop Operating System Market Share Asia». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ «Desktop Operating System Market Share United States Of America». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ «Desktop Operating System Market Share North America». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ Vaughan-Nichols, Steven (6 November 2017). «MINIX: Intel’s hidden in-chip operating system». ZDNET. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ a b «Windows comes up third in OS clash two years early». 1 April 2016. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- ^ «Gartner Forecasts Worldwide Device Shipments to Decline 14% in 2020 Due to Coronavirus Impact». Gartner. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ^ «Gartner Says Worldwide Device Shipments Will Increase 2.1 Percent in 2018». 29 January 2018. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- ^ «Gartner: Windows OS device shipments will falter in 2017». 10 January 2017. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- ^ «Gartner Says Tablet Sales Continue to Be Slow in 2015». 5 January 2015. Archived from the original on 7 January 2015. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ^ «Gartner Says Worldwide Traditional PC, Tablet, Ultramobile and Mobile Phone Shipments to Grow 4.2 Percent in 2014». 7 July 2014. Archived from the original on 11 July 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ^ «Gartner Says Worldwide PC, Tablet and Mobile Phone Shipments to Grow 4.5 Percent in 2013 as Lower-Priced Devices Drive Growth». 21 October 2013. Archived from the original on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ^ «Gartner Says Worldwide End-User Spending on Devices Will Grow 2 Percent in 2017, While Unit Shipments Remain Flat». Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ^ Thurrott, Paul (27 January 2016). «Apple’s active installed base is now over 1 billion strong». Thurrott.com. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

there are three big personal computing platforms. And only one of them is actually declining. We’ll see how Windows 10 fares over the long term, but even if Microsoft hits the 1 billion figure in 1-2 years as promised, it will by then still be the smallest of those three platforms.

- ^ «Gartner Says Worldwide PC Shipments Declined 8.3 Percent in Fourth Quarter of 2015: Holiday Sales Provided Little Cheer to PC Vendors in 2015» (Press release). 12 January 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- ^ Fuscaldo, Donna (18 July 2016). «Microsoft Backs Away From Windows 10 Goal (MSFT)». investopedia.com. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- ^ Foley, Mary Jo. «Microsoft: Windows 10 now on 400 million devices». ZDNet.

- ^ Foley, Mary Jo. «Microsoft says Windows 10 is now on more than 800 million devices». ZDNet. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ «Gartner Says Worldwide PC Shipments Grew 10.7% in Fourth Quarter of 2020 and 4.8% for the Year». Gartner. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ^ «Global PC shipments pass 340 million in 2021 and 2022 is set to be even stronger». Catalyst. 12 January 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2023.

- ^ «Gartner Says Worldwide PC Shipments Declined 28.5% in Fourth Quarter of 2022 and 16.2% for the Year». Gartner. Retrieved 29 December 2023.

- ^ «Tablet Users to Surpass 1 Billion Worldwide in 2015 — eMarketer». emarketer.com. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- ^ «Tablets have banner 2015». 1 January 2016.

- ^ «IDC: Tablet Shipments Decline For Fifth Straight Quarter — Androidheadlines.com». androidheadlines.com. 1 February 2016. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- ^ Eric Smith (29 July 2022). «Strategy Analytics: Android Tablet Market Share Falls Below 50% for First Time in 10 Years». Strategy Analytics. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ^ «Global tablet shipments by OS 2010-2020». Statista. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ^ Eric Smith (23 November 2015). «Tablets: Windows fast becoming a premium OS, says Strategy Analytics». Strategy Analytics. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ^ a b Lunden, Ingrid (3 March 2014). «Gartner: 195M Tablets Sold In 2013, Android Grabs Top Spot From iPad With 62% Share». Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- ^ «Ultramobiles». Gartner, Inc. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ^ «Are there Really More Mobile Phone Owners than Toothbrush Owners?». www.linkedin.com. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ^ Turner, Ash (10 July 2018). «1 Billion More Phones Than People In The World! BankMyCell». BankMyCell. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ^ «Android is now used by 1.4 billion people». The Verge. 29 September 2015.

- ^ «Google I/O website: Keynote». Archived from the original on 18 June 2015. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ^ Protalinski, Emil (17 May 2017). «Android passes 2 billion monthly active devices». VentureBeat. Retrieved 17 May 2017.

- ^ Ng, Alfred (17 May 2017). «Google’s Android now powers more than 2 billion devices». CNET. CBS Interactive. Retrieved 17 May 2017.

- ^ Parrack, Dave (18 August 2016). «Android Is Killing iOS, Uber Launches Self-Driving Cars… [Tech News Digest]». MUO. Retrieved 18 April 2025.

- ^ «Gartner Says Five of Top 10 Worldwide Mobile Phone Vendors Increased Sales in Second Quarter of 2016: Global Sales of Smartphones Grew 4.3 Percent Year on Year» (Press release). Gartner. 19 August 2016.

- ^ Patrick, Seitz (3 November 2016). «Apple iPhone Grabs 104% Of Smartphone Industry Profit In Q3». Investor’s Business Daily.

- ^ Gadgets Now Bureau, «World’s 5 biggest smartphone companies», Gadgets Now, 1 Aug 2018, 02.51 PM IST

- ^ Kirton, David (26 November 2024). «Huawei launches Mate 70 smartphone as new US chip curbs loom». Reuters. Retrieved 9 April 2025.

- ^ Enrico, Jose (12 October 2024). «HarmonyOS Next Could Be the Next iOS, Android OS Replacement: What’s the Difference?». Tech Times. Retrieved 9 April 2025.

- ^ Baloch, Huzefa (22 October 2024). «Huawei launches HarmonyOS NEXT as a complete Android replacement». Notebookcheck. Retrieved 9 April 2025.

- ^ «Global Smartphone Sales Share by Operating System». www.counterpointresearch.com. Retrieved 29 March 2025.

- ^ «Gartner Says Worldwide Sales of Smartphones Returned to Growth in First Quarter of 2018». 28 May 2018. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- ^ «GGartner Says Worldwide Sales of Smartphones Recorded First Ever Decline During the Fourth Quarter of 2017» (Press release). 22 February 2018. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- ^ «Gartner Says Worldwide Sales of Smartphones Grew 9 Percent in First Quarter of 2017». Retrieved 2 February 2018.

- ^ «GGartner Says Worldwide Sales of Smartphones Recorded First Ever Decline During the Fourth Quarter of 2017» (Press release). 22 February 2018. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- ^ «Gartner Says Worldwide Sales of Smartphones Grew 7 Percent in the Fourth Quarter of 2016». Retrieved 2 February 2018.

- ^ «Gartner Says Chinese Smartphone Vendors Were Only Vendors in the Global Top Five to Increase Sales in the Third Quarter of 2016» (Press release). Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- ^ «Gartner Says Five of Top 10 Worldwide Mobile Phone Vendors Increased Sales in the Second Quarter of 2016» (Press release). Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- ^ «Gartner Says Worldwide Smartphone Sales Grew 3.9 Percent in the First Quarter of 2016» (Press release). Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- ^ «Gartner Says Worldwide Smartphone Sales Grew 9.7 Percent in the Fourth Quarter of 2015» (Press release). 18 February 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- ^ «Gartner Says Worldwide Smartphone Sales Recorded Slowest Growth Rate Since 2013» (Press release). 20 August 2015. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- ^ «Gartner Says Worldwide Smartphone Sales Grew 9.7 Percent in Fourth Quarter of 2015» (Press release). 18 February 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- ^ «Android Captures Record 81 Percent Share of Global Smartphone Shipments in Q3 2013». Archived from the original on 1 November 2013. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ^ «Gartner Says Worldwide Smartphone Sales Recorded Slowest Growth Rate Since 2013» (Press release). 20 August 2015. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- ^ «Worldwide Smartphone Sales to End Users by Operating System in 2Q13» (Press release).

- ^ «Worldwide Smartphone Sales to End Users by Operating System in 1Q13» (Press release).

- ^ «Android and iOS Combine for 92.3% of All Smartphone Operating System Shipments in the First Quarter While Windows Phone Leapfrogs BlackBerry, According to IDC». www.businesswire.com. 16 May 2013.

- ^ «Operating System Market Share Worldwide». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 18 November 2024.

- ^ a b «Android overtakes Windows for first time: «Milestone in technology history and end of an era» as Microsoft no longer owns dominant OS» (Press release).

- ^ «StatCounter Global Stats — Browser, OS, Search Engine including Mobile Usage Share». statcounter.com. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- ^ «Operating System Market Share South America». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ «Operating System Market Share Africa». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ «Operating System Market Share Guam». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- ^ «Operating System Market Share Guam». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

- ^ «Operating System Market Share Guam». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- ^ «Operating System Market Share Falkland Islands (malvinas): Q3 2018 — Q2 2019». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

- ^ «Operating System Market Share Falkland Islands (malvinas)». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

- ^ «Operating System Market Share Sweden». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

- ^ «Operating System Market Share Madagascar». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- ^ «Browser Version Market Share Madagascar». StatCounter Global Stats.

- ^ «Browser Market Share Madagascar». StatCounter Global Stats.

- ^ «StatCounter Global Stats — Browser, OS, Search Engine including Mobile Usage Share». statcounter.com. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- ^ «Top 8 Operating Systems in Asia from July 2014 to September 2019». statcounter.com.

- ^ a b «Operating System Market Share Bangladesh». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- ^ «Top 8 Operating Systems in Africa from July 2014 to Apr 2016». statcounter.com.

- ^ «StatCounter Global Stats — Browser, OS, Search Engine including Mobile Usage Share». statcounter.com. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- ^ «Global stats». W3 Counter.

- ^ «StatCounter Global Stats — Browser, OS, Search Engine including Mobile Usage Share». statcounter.com. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- ^ «W3Counter: Global Web Stats — February 2025». www.w3counter.com. Retrieved 29 March 2025.

- ^ «W3Counter: Global Web Stats — October 2022». www.w3counter.com. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ «W3Counter: Global Web Stats — October 2020». www.w3counter.com. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ^ a b «Global stats». W3 Counter.

- ^ «Global stats». W3 Counter.

- ^ a b «StatCounter Stats through Dec 2016». www.statcounter.com. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ^ «Worldwide user OS families in Jul 2016».

- ^ a b «Worldwide user OS families in Dec 2015».

- ^ «Wikimedia Traffic Analysis Report — Operating Systems, 28Nov2016-1Jan2017».

- ^ «Desktop Operating System Market Share Worldwide». StatCounter Global Stats.

- ^ «Operating System Market Share United States Of America». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^ «Operating System Market Share Worldwide». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^ «Desktop Operating System Market Share United States Of America». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^ https://gs.statcounter.com/#desktop-os-ww-monthly-201508-201508-bar StatCounter

- ^ «Software Pirates in China Beat Microsoft to the Punch». The New York Times. 19 October 2009.

- ^ «Around 25–35% of Windows XP systems are pirated (calculations included)». Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ «Desktop Windows Version Market Share Armenia». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- ^ «StatCounter Global Stats — Browser, OS, Search Engine including Mobile Usage Share». statcounter.com. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- ^ «StatCounter Global Stats — Browser, OS, Search Engine including Mobile Usage Share». statcounter.com. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- ^ «Top 7 Desktop OSs in Asia on May 2016». StatCounter. May 2016. Retrieved 9 April 2016.

- ^ «Desktop Operating System Market Share North America». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

- ^ «Desktop Operating System Market Share United States Of America». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

- ^ «Desktop Operating System Market Share Asia». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

- ^ «Desktop vs Mobile vs Tablet vs Console Market Share Worldwide». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- ^ «Desktop vs Mobile vs Tablet vs Console Market Share Worldwide». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ^ «Desktop vs Mobile vs Tablet vs Console Market Share Worldwide». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ «Desktop vs Mobile vs Tablet vs Console Market Share Oceania». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- ^ «Desktop vs Mobile vs Tablet vs Console Market Share Europe». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- ^ «Desktop vs Mobile vs Tablet vs Console Market Share North America». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- ^ «Desktop vs Mobile vs Tablet vs Console Market Share United States Of America». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ «Desktop vs Mobile vs Tablet vs Console Market Share North America». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ «Desktop vs Mobile vs Tablet vs Console Market Share United States Of America». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- ^ «Desktop vs Mobile vs Tablet vs Console Market Share United States Of America». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- ^ «Desktop vs Mobile vs Tablet vs Console Market Share United States Of America». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

- ^ «Desktop vs Mobile vs Tablet vs Console Market Share United States Of America». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

- ^ «Desktop vs Mobile vs Tablet vs Console Market Share United States Of America». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

- ^ «Desktop vs Mobile vs Tablet vs Console Market Share Worldwide». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- ^ «Desktop vs Mobile vs Tablet vs Console Market Share United States Of America». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ^ «Desktop vs Mobile vs Tablet vs Console Market Share United States Of America». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ^ «Stack Overflow 2023 Developer Survey, Operating System». Stack Overflow. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

- ^ «Windows 10 has over 50 percent market share, according to Microsoft — wait, what?». BetaNews. 29 August 2016.

- ^ «Steam Hardware & Software Survey: December 2023». 2 January 2024. Archived from the original on 2 January 2024. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ a b Steam Hardware & Software Survey: December 2022, archived from the original on 4 January 2023, retrieved 31 January 2023

- ^ Steam Hardware & Software Survey: December 2019, archived from the original on 2 January 2020

- ^ Steam Hardware & Software Survey: January 2019, archived from the original on 11 February 2019

- ^ Steam Hardware & Software Survey: December 2018, archived from the original on 12 February 2018

- ^ Steam Hardware & Software Survey, archived from the original on 12 February 2017

- ^ Steam Hardware & Software Survey, archived from the original on 10 February 2016

- ^ Steam Hardware & Software Survey, archived from the original on 16 February 2015

- ^ Steam Hardware & Software Survey, archived from the original on 15 February 2014

- ^ «Linux gaming is much healthier than Steam’s Hardware Survey implies». pcworld.com. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- ^ «Gartner Says Worldwide Sales of Smartphones Returned to Growth in First Quarter of 2018». Gartner, Inc. Gartner. 29 May 2018. Archived from the original on 13 June 2018. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- ^ «Desktop vs Mobile vs Tablet vs Console Market Share Russian Federation | StatCounter Global Stats». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- ^ «Desktop vs Mobile vs Tablet vs Console Market Share Mali | StatCounter Global Stats». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- ^ «Operating System Market Share Mali». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- ^ Bates, Adam. «InsightPortal | Higher GDP per capita corresponds with more Apple devices, stats suggest». www.insightportal.io. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- ^ «Google Mobile App Marketing Insights: Asia» (PDF). storage.googleapis.com.

- ^ «Mobile Operating System Market Share India». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- ^ «Mobile operating systems’ market share worldwide from 1st quarter 2009 to 4th quarter 2022». Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ «Mobile Operating System Market Share Worldwide». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- ^ «Mobile Operating System Market Share Worldwide». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ^ a b c «StatCounter Global Stats — Browser, OS, Search Engine including Mobile Usage Share». StatCounter Global Stats.

- ^ «Comscore Reports April 2017 U.S. Smartphone Subscriber Market Share». comScore, Inc. 8 June 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- ^ «comScore Reports January 2016 U.S. Smartphone Subscriber Market Share». comScore, Inc. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- ^ «comScore Reports January 2015 U.S. Smartphone Subscriber Market Share». comScore. 4 March 2015. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- ^ «comScore Reports January 2014 U.S. Smartphone Subscriber Market Share — comScore, Inc». comScore. 7 March 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- ^ «Comscore Reports February 2012 U.S. Mobile Subscriber Market Share: Android Captures Majority Share of U.S. Smartphone Market». comScore, Inc. 3 April 2012. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- ^ «comScore Reports December 2010 U.S. Mobile Subscriber Market Share: Number of Smartphone Users Up 60 Percent Versus Year Agoe». comScore, Inc. 7 February 2011. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- ^ «Tablet Operating System Market Share Worldwide — July 2018». StatCounter. 29 May 2018. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- ^ «StatCounter Global Stats — Browser, OS, Search Engine including Mobile Usage Share». statcounter.com. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- ^ «StatCounter Global Stats — Browser, OS, Search Engine including Mobile Usage Share». statcounter.com. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ^ «StatCounter Global Stats — Browser, OS, Search Engine including Mobile Usage Share». statcounter.com. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ^ «StatCounter Global Stats — Browser, OS, Search Engine including Mobile Usage Share». statcounter.com. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- ^ «StatCounter Global Stats — Browser, OS, Search Engine including Mobile Usage Share». statcounter.com. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- ^ «StatCounter Global Stats — Browser, OS, Search Engine including Mobile Usage Share». statcounter.com.

- ^ «StatCounter Global Stats — Browser, OS, Search Engine including Mobile Usage Share». statcounter.com.

- ^ «StatCounter Global Stats — Browser, OS, Search Engine including Mobile Usage Share». statcounter.com.

- ^ «StatCounter Global Stats — Browser, OS, Search Engine including Mobile Usage Share». statcounter.com.

- ^ «StatCounter Global Stats — Browser, OS, Search Engine including Mobile Usage Share». statcounter.com.

- ^ a b «StatCounter Global Stats — Browser, OS, Search Engine including Mobile Usage Share». statcounter.com.

- ^ «Top 7 Tablet OSes in South America from Aug 2012 to Aug 2015». statcounter.com.

- ^ «StatCounter Global Stats — Browser, OS, Search Engine including Mobile Usage Share». statcounter.com.

- ^ «Top 7 Tablet OSes in South America from Aug 2012 to Sep 2015». statcounter.com.

- ^ «StatCounter Global Stats — Browser, OS, Search Engine including Mobile Usage Share». statcounter.com.

- ^ «StatCounter Global Stats — Browser, OS, Search Engine including Mobile Usage Share». statcounter.com.

- ^ «StatCounter Global Stats — Browser, OS, Search Engine including Mobile Usage Share». statcounter.com.

- ^ «Tablet Operating System Market Share Worldwide». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 11 September 2023.

- ^ «Tablet Operating System Market Share Worldwide». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ^ «Tablet Operating System Market Share Worldwide». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ^ «Tablet Operating System Market Share Worldwide». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ^ Global Stats Top 7 Tablet OSs from Jan to Aug 2015. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- ^ Global Stats Top 7 Tablet OSs from Feb 2015. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ^ Global Stats Top 7 Tablet OSs from Oct 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- ^ «Operating System Market Share United States Of America». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- ^ «Desktop vs mobile vs tablet vs console market share Worldwide — StatCounter Global Stats». StatCounter Global Stats.

- ^ «Operating System Market Share Worldwide | StatCounter Global Stats». StatCounter Global Stats. Retrieved 10 April 2018.