Для преобразования объекта пути (pathlib.Path(), pathlib.PurePath() и их подклассов) в строку, используйте функцию str():

Преобразование объекта пути в строку:

Для того ,что бы преобразовать объект пути в строку, просто передайте его в функцию str().

>>> import pathlib >>> p = pathlib.Path('myfile.txt') >>> p # PosixPath('myfile.txt') >>> str(p) # 'myfile.txt' >>> p = pathlib.PurePath('myfile.txt') >>> p # PurePosixPath('myfile.txt') >>> str(p) # 'myfile.txt'

When working with file paths in Python 3, it’s important to understand how to properly write Windows paths. Windows uses a different syntax for file paths compared to Unix-based systems, and Python provides various string literals to handle these differences. In this guide, we will explore the different ways to write Windows paths in Python 3 using string literals.

Using Single Backslashes

In Windows, file paths are typically represented using backslashes (\) as the directory separator. However, in Python strings, the backslash is used as an escape character. To represent a backslash in a Windows path, we need to use a double backslash (\\) or a raw string literal.

path = "C:\\Users\\Username\\Documents\\file.txt"

In the example above, we use double backslashes to represent each backslash in the Windows path. This ensures that the backslashes are interpreted correctly as directory separators.

An alternative approach is to use a raw string literal, denoted by the ‘r’ prefix. With a raw string literal, backslashes are treated as literal characters and not escape characters.

path = r"C:\Users\Username\Documents\file.txt"

Both approaches are valid and achieve the same result. Choose the one that suits your preference or coding style.

Using Forward Slashes

While Windows primarily uses backslashes as directory separators, Python also supports forward slashes (/) as an alternative. This is because forward slashes are the standard directory separators in Unix-based systems, and Python aims to be cross-platform.

path = "C:/Users/Username/Documents/file.txt"

In the example above, we use forward slashes to represent the directory separators in the Windows path. Python automatically converts the forward slashes to backslashes when interacting with the underlying operating system.

Using forward slashes can make your code more portable and easier to read, especially if you are working on a project that needs to run on both Windows and Unix-based systems.

Using the pathlib Module

Python 3 introduced the pathlib module, which provides an object-oriented approach to working with file paths. The Path class in the pathlib module allows you to create and manipulate file paths in a platform-independent manner.

from pathlib import Path

path = Path("C:/Users/Username/Documents/file.txt")

In the example above, we create a Path object representing the Windows path. The Path class automatically handles the conversion of forward slashes to backslashes when necessary.

The pathlib module provides a wide range of methods and properties to manipulate file paths, such as joinpath() to concatenate paths and exists() to check if a path exists. It’s a powerful tool for working with file paths in a platform-independent way.

Writing Windows paths in Python 3 requires understanding the syntax differences between Windows and Unix-based systems. By using double backslashes, raw string literals, or forward slashes, you can accurately represent Windows paths in Python. Additionally, the pathlib module provides an object-oriented approach to working with file paths, making it easier to handle platform-specific differences. With these techniques, you can confidently work with Windows paths in your Python projects.

Example 1: Creating a Windows path using string literals

# Import the os module import os # Create a Windows path using string literals path = "C:\\Users\\John\\Documents\\file.txt" # Print the path print(path)

This example demonstrates how to create a Windows path using string literals in Python. The backslashes in the path are escaped using an additional backslash. The resulting path is then printed to the console.

Example 2: Joining Windows paths using the os module

# Import the os module import os # Create two Windows paths using string literals path1 = "C:\\Users\\John\\Documents" path2 = "file.txt" # Join the paths using the os module joined_path = os.path.join(path1, path2) # Print the joined path print(joined_path)

In this example, two Windows paths are created using string literals. The os.path.join() function is then used to join the paths together, taking care of the correct path separator for the operating system. The resulting joined path is printed to the console.

Example 3: Checking if a path is absolute using the os module

# Import the os module import os # Create a Windows path using string literals path = "C:\\Users\\John\\Documents\\file.txt" # Check if the path is absolute is_absolute = os.path.isabs(path) # Print the result print(is_absolute)

This example demonstrates how to check if a Windows path is absolute using string literals and the os module. The os.path.isabs() function is used to determine if the path is absolute or not. The result is then printed to the console.

Reference Links:

- Python 3 Documentation: os.path

- GeeksforGeeks: os.path.join() in Python

- GeeksforGeeks: os.path.isabs() in Python

Conclusion:

In Python 3, writing Windows paths using string literals can be done by escaping backslashes or using raw string literals. The os module provides useful functions for manipulating and working with Windows paths, such as joining paths and checking if a path is absolute. By understanding these concepts and utilizing the os module, developers can effectively handle Windows paths in their Python programs.

Watch Now This tutorial has a related video course created by the Real Python team. Watch it together with the written tutorial to deepen your understanding: Using Python’s pathlib Module

Python’s pathlib module helps streamline your work with file and directory paths. Instead of relying on traditional string-based path handling, you can use the Path object, which provides a cross-platform way to read, write, move, and delete files.

pathlib also brings together functionality previously spread across other libraries like os, glob, and shutil, making file operations more straightforward. Plus, it includes built-in methods for reading and writing text or binary files, ensuring a clean and Pythonic approach to handling file tasks.

By the end of this tutorial, you’ll understand that:

pathlibprovides an object-oriented interface for managing file and directory paths in Python.- You can instantiate

Pathobjects using class methods like.cwd(),.home(), or by passing strings toPath. pathliballows you to read, write, move, and delete files efficiently using methods.- To get a list of file paths in a directory, you can use

.iterdir(),.glob(), or.rglob(). - You can use

pathlibto check if a path corresponds to a file by calling the.is_file()method on aPathobject.

You’ll also explore a bunch of code examples in this tutorial, which you can use for your everyday file operations. For example, you’ll dive into counting files, finding the most recently modified file in a directory, and creating unique filenames.

It’s great that pathlib offers so many methods and properties, but they can be hard to remember on the fly. That’s where a cheat sheet can come in handy. To get yours, click the link below:

The Problem With Representing Paths as Strings

With Python’s pathlib, you can save yourself some headaches. Its flexible Path class paves the way for intuitive semantics. Before you have a closer look at the class, take a moment to see how Python developers had to deal with paths before pathlib was around.

Traditionally, Python has represented file paths using regular text strings. However, since paths are more than plain strings, important functionality was spread all around the standard library, including in libraries like os, glob, and shutil.

As an example, the following code block moves files into a subfolder:

You need three import statements in order to move all the text files to an archive directory.

Python’s pathlib provides a Path class that works the same way on different operating systems.

Instead of importing different modules such as glob, os, and shutil, you can perform the same tasks by using pathlib alone:

Just as in the first example, this code finds all the text files in the current directory and moves them to an archive/ subdirectory.

However, with pathlib, you accomplish these tasks with fewer import statements and more straightforward syntax, which you’ll explore in depth in the upcoming sections.

Path Instantiation With Python’s pathlib

One motivation behind pathlib is to represent the file system with dedicated objects instead of strings. Fittingly, the official documentation of pathlib is called pathlib — Object-oriented filesystem paths.

The object-oriented approach is already quite visible when you contrast the pathlib syntax with the old os.path way of doing things. It gets even more obvious when you note that the heart of pathlib is the Path class:

If you’ve never used this module before or just aren’t sure which class is right for your task,

Pathis most likely what you need. (Source)

In fact, Path is so frequently used that you usually import it directly:

Because you’ll mainly be working with the Path class of pathlib, this way of importing Path saves you a few keystrokes in your code. This way, you can work with Path directly, rather than importing pathlib as a module and referring to pathlib.Path.

There are a few different ways of instantiating a Path object. In this section, you’ll explore how to create paths by using class methods, passing in strings, or joining path components.

Using Path Methods

Once you’ve imported Path, you can make use of existing methods to get the current working directory or your user’s home directory.

The current working directory is the directory in the file system that the current process is operating in. You’ll need to programmatically determine the current working directory if, for example, you want to create or open a file in the same directory as the script that’s being executed.

Additionally, it’s useful to know your user’s home directory when working with files. Using the home directory as a starting point, you can specify paths that’ll work on different machines, independent of any specific usernames.

To get your current working directory, you can use .cwd():

- Windows

- Linux

- macOS

When you instantiate pathlib.Path, you get either a WindowsPath or a PosixPath object.

The kind of object will depend on which operating system you’re using.

On Windows, .cwd() returns a WindowsPath. On Linux and macOS, you get a PosixPath.

Despite the differences under the hood, these objects provide identical interfaces for you to work with.

It’s possible to ask for a WindowsPath or a PosixPath explicitly, but you’ll only be limiting your code to that system without gaining any benefits. A concrete path like this won’t work on a different system:

But what if you want to manipulate Unix paths on a Windows machine, or vice versa? In that case, you can directly instantiate PureWindowsPath or PurePosixPath on any system.

When you make a path like this, you create a PurePath object under the hood. You can use such an object if you need a representation of a path without access to the underlying file system.

Generally, it’s a good idea to use Path. With Path, you instantiate a concrete path for the platform that you’re using while also keeping your code platform-independent. Concrete paths allow you to do system calls on path objects, but pure paths only allow you to manipulate paths without accessing the operating system.

Working with platform-independent paths means that you can write a script on Windows that uses Path.cwd(), and it’ll work correctly when you run the file on macOS or Linux.

The same is true for .home():

- Windows

- Linux

- macOS

With Path.cwd() and Path.home(), you can conveniently get a starting point for your Python scripts.

In cases where you need to spell paths out or reference a subdirectory structure, you can instantiate Path with a string.

Passing in a String

Instead of starting in your user’s home directory or your current working directory, you can point to a directory or file directly by passing its string representation into Path:

- Windows

- Linux

- macOS

This process creates a Path object. Instead of having to deal with a string, you can now work with the flexibility that pathlib offers.

On Windows, the path separator is a backslash (\). However, in many contexts, the backslash is also used as an escape character to represent non-printable characters. To avoid problems, use raw string literals to represent Windows paths:

A string with an r in front of it is a raw string literal. In raw string literals, the \ represents a literal backslash. In a normal string, you’d need to use two backslashes (\\) to indicate that you want to use the backslash literally and not as an escape character.

You may have already noticed that although you enter paths on Windows with backslashes, pathlib represents them with the forward slash (/) as the path separator. This representation is named POSIX style.

POSIX stands for Portable Operating System Interface, which is a standard for maintaining the compability between operating systems. The standard covers much more than path representation. You can learn more about it in Open Group Base Specifications Issue 7.

Still, when you convert a path back to a string, it’ll use the native form—for example, with backslashes on Windows:

In general, you should try to use Path objects as much as possible in your code to take advantage of their benefits, but converting them to strings can be necessary in certain contexts. Some libraries and APIs still expect you to pass file paths as strings, so you may need to convert a Path object to a string before passing it to certain functions.

Joining Paths

A third way to construct a path is to join the parts of the path using the special forward slash operator (/), which is possibly the most unusual part of the pathlib library. You may have already raised your eyebrows about it in the example at the beginning of this tutorial:

The forward slash operator can join several paths or a mix of paths and strings as long as you include one Path object.

You use a forward slash regardless of your platform’s actual path separator.

If you don’t like the special slash notation, then you can do the same operation with the .joinpath() method:

This notation is closer to os.path.join(), which you may have used in the past. It can feel more familiar than a forward slash if you’re used to backslashed paths.

After you’ve instantiated Path, you probably want to do something with your path. For example, maybe you’re aiming to perform file operations or pick parts from the path. That’s what you’ll do next.

File System Operations With Paths

You can perform a bunch of handy operations on your file system using pathlib.

In this section, you’ll get a broad overview of some of the most common ones. But before you start performing file operations, have a look at the parts of a path first.

Picking Out Components of a Path

A file or directory path consists of different parts. When you use pathlib, these parts are conveniently available as properties. Basic examples include:

.name: The filename without any directory.stem: The filename without the file extension.suffix: The file extension.anchor: The part of the path before the directories.parent: The directory containing the file, or the parent directory if the path is a directory

Here, you can observe these properties in action:

- Windows

- Linux

- macOS

Note that .parent returns a new Path object, whereas the other properties return strings. This means, for instance, that you can chain .parent in the last example or even combine it with the slash operator to create completely new paths:

That’s quite a few properties to keep straight. If you want a handy reference for these Path properties, then you can download the Real Python pathlib cheat sheet by clicking the link below:

Reading and Writing Files

Consider that you want to print all the items on a shopping list that you wrote down in a Markdown file. The content of shopping_list.md looks like this:

Traditionally, the way to read or write a file in Python has been to use the built-in open() function.

With pathlib, you can use open() directly on Path objects.

So, a first draft of your script that finds all the items in shopping_list.md and prints them may look like this:

Python

read_shopping_list.py

In fact, Path.open() is calling the built-in open() function behind the scenes. That’s why you can use parameters like mode and encoding with Path.open().

On top of that, pathlib offers some convenient methods to read and write files:

.read_text()opens the path in text mode and returns the contents as a string..read_bytes()opens the path in binary mode and returns the contents as a byte string..write_text()opens the path and writes string data to it..write_bytes()opens the path in binary mode and writes data to it.

Each of these methods handles the opening and closing of the file. Therefore, you can update read_shopping_list.py using .read_text():

Python

read_shopping_list.py

You can also specify paths directly as filenames, in which case they’re interpreted relative to the current working directory. So you can condense the example above even more:

Python

read_shopping_list.py

If you want to create a plain shopping list that only contains the groceries, then you can use .write_text() in a similar fashion:

Python

write_plain_shoppinglist.py

When using .write_text(), Python overwrites any existing files on the same path without giving you any notice. That means you could erase all your hard work with a single keystroke!

As always, when you write files with Python, you should be cautious of what your code is doing. The same is true when you’re renaming files.

Renaming Files

When you want to rename files, you can use .with_stem(), .with_suffix(), or .with_name(). They return the original path but with the filename, the file extension, or both replaced.

If you want to change a file’s extension, then you can use .with_suffix() in combination with .replace():

Using .with_suffix() returns a new path. To actually rename the file, you use .replace(). This moves txt_path to md_path and renames it when saving.

If you want to change the complete filename, including the extension, then you can use .with_name():

The code above renames hello.txt to goodbye.md.

If you want to rename the filename only, keeping the suffix as it is, then you can use .with_stem(). You’ll explore this method in the next section.

Copying Files

Surprisingly, Path doesn’t have a method to copy files. But with the knowledge that you’ve gained about pathlib so far, you can create the same functionality with a few lines of code:

You’re using .with_stem() to create the new filename without changing the extension.

The actual copying takes place in the highlighted line, where you use .read_bytes() to read the content of source and then write this content to destination using .write_bytes().

While it’s tempting to use pathlib for everything path related, you may also consider using shutil for copying files. It’s a great alternative that also knows how to work with Path objects.

Moving and Deleting Files

Through pathlib, you also have access to basic file system–level operations like moving, updating, and even deleting files. For the most part, these methods don’t give a warning or wait for confirmation before getting rid of information or files. So, be careful when using these methods.

To move a file, you can use .replace(). Note that if the destination already exists, then .replace() will overwrite it. To avoid possibly overwriting the destination path, you can test whether the destination exists before replacing:

However, this does leave the door open for a possible race condition. Another process may add a file at the destination path between the execution of the if statement and the .replace() method. If that’s a concern, then a safer way is to open the destination path for exclusive creation then explicitly copy the source data and delete the source file afterward:

If destination already exists, then the code above catches a FileExistsError and prints a warning. To perform a move, you need to delete source with .unlink() after the copy is done. Using else ensures that the source file isn’t deleted if the copying fails.

Creating Empty Files

To create an empty file with pathlib, you can use .touch().

This method is intended to update a file’s modification time, but you can use its side effect to create a new file:

In the example above, you instantiate a Path object and create the file using .touch(). You use .exists() both to verify that the file didn’t exist before and then to check that it was successfully created.

If you use .touch() again, then it updates the file’s modification time.

If you don’t want to modify files accidentally, then you can use the exist_ok parameter and set it to False:

When you use .touch() on a file path that doesn’t exist, you create a file without any content.

Creating an empty file with Path.touch() can be useful when you want to reserve a filename for later use, but you don’t have any content to write to it yet. For example, you may want to create an empty file to ensure that a certain filename is available, even if you don’t have content to write to it at the moment.

Python pathlib Examples

In this section, you’ll see some examples of how to use pathlib to deal with everyday challenges that you’re facing as a Python developer.

You can use these examples as starting points for your own code or save them as code snippets for later reference.

Counting Files

There are a few different ways to get a list of all the files in a directory with Python. With pathlib, you can conveniently use the .iterdir() method, which iterates over all the files in the given directory. In the following example, you combine .iterdir() with the collections.Counter class to count how many files of each file type are in the current directory:

You can create more flexible file listings with the methods .glob() and .rglob(). For example, Path.cwd().glob("*.txt") returns all the files with a .txt suffix in the current directory. In the following, you only count file extensions starting with p:

If you want to recursively find all the files in both the directory and its subdirectories, then you can use .rglob(). This method also offers a cool way to display a directory tree, which is the next example.

Displaying a Directory Tree

In this example, you define a function named tree(), which will print a visual tree representing the file hierarchy, rooted at a given directory. This is useful when, for example, you want to peek into the subdirectories of a project.

To traverse the subdirectories as well, you use the .rglob() method:

Python

display_dir_tree.py

Note that you need to know how far away from the root directory a file is located. To do this, you first use .relative_to() to represent a path relative to the root directory. Then, you use the .parts property to count the number of directories in the representation. When run, this function creates a visual tree like the following:

If you want to push this code to the next level, then you can try building a directory tree generator for the command line.

Finding the Most Recently Modified File

The .iterdir(), .glob(), and .rglob() methods are great fits for generator expressions and list comprehensions. To find the most recently modified file in a directory, you can use the .stat() method to get information about the underlying files. For instance, .stat().st_mtime gives the time of last modification of a file:

The timestamp returned from a property like .stat().st_mtime represents seconds since January 1, 1970, also known as the epoch. If you’d prefer a different format, then you can use time.localtime or time.ctime to convert the timestamp to something more usable. If this example has sparked your curiosity, then you may want learn more about how to get and use the current time in Python.

Creating a Unique Filename

In the last example, you’ll construct a unique numbered filename based on a template string.

This can be handy when you don’t want to overwrite an existing file if it already exists:

In unique_path(), you specify a pattern for the filename, with room for a counter. Then, you check the existence of the file path created by joining a directory and the filename, including a value for the counter. If it already exists, then you increase the counter and try again.

Now you can use the script above to get unique filenames:

If the directory already contains the files test001.txt and test002.txt, then the above code will set path to test003.txt.

Conclusion

Python’s pathlib module provides a modern and Pythonic way of working with file paths, making code more readable and maintainable.

With pathlib, you can represent file paths with dedicated Path objects instead of plain strings.

In this tutorial, you’ve learned how to:

- Work with file and directory paths in Python

- Instantiate a

Pathobject in different ways - Use

pathlibto read and write files - Carefully copy, move, and delete files

- Manipulate paths and the underlying file system

- Pick out components of a path

The pathlib module makes dealing with file paths convenient by providing helpful methods and properties.

Peculiarities of the different systems are hidden by the Path object, which makes your code more consistent across operating systems.

If you want to get an overview PDF of the handy methods and properties that pathlib offers, then you can click the link below:

Frequently Asked Questions

Now that you have some experience with Python’s pathlib module, you can use the questions and answers below to check your understanding and recap what you’ve learned.

These FAQs are related to the most important concepts you’ve covered in this tutorial. Click the Show/Hide toggle beside each question to reveal the answer.

The pathlib module provides a more intuitive and readable way to handle file paths with its object-oriented approach, methods, and attributes, reducing the need to import multiple libraries and making your code more platform-independent.

You can instantiate a Path object by importing Path from pathlib and then using Path() with a string representing the file or directory path. You can also use class methods like Path.cwd() for the current working directory or Path.home() for the user’s home directory.

You can check if a path is a file by using the .is_file() method on a Path object. This method returns True if the path points to a file and False otherwise.

You can join paths using the forward slash operator (/) or the .joinpath() method to combine path components into a single Path object.

You can read a file using pathlib by creating a Path object for the file and then calling the .read_text() method to get the file’s contents as a string. Alternatively, use .open() with a with statement to read the file using traditional file handling techniques.

You can use the .touch() method of a Path object to create an empty file with pathlib.

You can use the .read_text() and .write_text() methods of a pathlib.Path object for reading and writing text files, and .read_bytes() and .write_bytes() for binary files. These methods handle file opening and closing for you.

You can create a unique filename by constructing a path with a counter in a loop, checking for the existence of the file using .exists(), and incrementing the counter until you find a filename that doesn’t exist.

Watch Now This tutorial has a related video course created by the Real Python team. Watch it together with the written tutorial to deepen your understanding: Using Python’s pathlib Module

When working with file paths in Python, it is important to properly write the path in the code to avoid any issues. In particular, when dealing with Windows paths, special attention must be given due to the backslash (\) acting as an escape character in Python string literals. This article will explain the best practices for writing Windows paths in Python string literals, along with examples to illustrate the solutions.

Understanding the Issue

The problem arises when trying to write a Windows path directly in a Python string literal. For example, let’s say we want to refer to the path C:\meshes\as. If we write it as «C:\meshes\as», we will encounter problems. This is because the backslash (\) is being treated as an escape character, leading to unexpected behavior.

One possible solution to this issue is to use raw strings by prefixing the string literal with the letter ‘r’. This tells Python to treat the string as a raw string, ignoring any escape characters. So, instead of «C:\meshes\as», we can write r»C:\meshes\as». This ensures that the path is interpreted correctly and avoids any escape character conflicts.

path = r"C:\meshes\as"

print(path)

# Output: C:\meshes\as

Alternate Escaping

Another way to solve this problem is by using double backslashes (\\) to escape the backslash character. This is because one backslash is treated as an escape character, but two backslashes are interpreted as a single backslash. So, instead of «C:\meshes\as», we can write «C:\\meshes\\as». This method can be used even without raw strings.

path = "C:\\meshes\\as"

print(path)

# Output: C:\meshes\as

Using os.path Module

Python’s os.path module provides a platform-independent way to handle file paths. It automatically adapts to the current operating system and handles the differences in path formats. Instead of manually writing the paths as discussed before, it is recommended to use the os.path functions to manipulate and construct file paths.

For example, to join two directory paths, you can use the os.path.join() function. This function takes care of the platform-specific separator and avoids any manual path string manipulation.

import os

directory1 = "C:\\meshes"

directory2 = "as"

path = os.path.join(directory1, directory2)

print(path)

# Output: C:\meshes\as

The os.path module also provides various other functions to perform operations on file paths, such as os.path.dirname() to get the directory name from a path, os.path.abspath() to get the absolute path, and many more. It is recommended to use these functions to ensure correct and portable file path handling in Python programs.

Conclusion

When writing Windows paths in Python string literals, it is important to consider how the backslash (\) is treated as an escape character. To avoid any issues, you can use raw strings by prefixing the string with the letter ‘r’ (e.g., r»C:\meshes\as»), or use double backslashes (\\) to explicitly escape the backslash character (e.g., «C:\\meshes\\as»). Alternatively, you can use the os.path module from Python’s standard library to handle file paths in a platform-independent manner. By following these best practices, you can ensure that your Python code correctly deals with Windows paths.

When I started learning Python, there was one thing I always had trouble with: dealing with directories and file paths!

I remember the struggle to manipulate paths as strings using the os module. I was constantly looking up error messages related to improper path manipulation.

The os module never felt intuitive and ergonomic to me, but my luck changed when pathlib landed in Python 3.4. It was a breath of fresh air, much easier to use, and felt more Pythonic to me.

The only problem was: finding examples on how to use it was hard; the documentation only covered a few use cases. And yes, Python’s docs are good, but for newcomers, examples are a must.

Even though the docs are much better now, they don’t showcase the module in a problem-solving fashion. That’s why I decided to create this cookbook.

This article is a brain dump of everything I know about pathlib. It’s meant to be a reference rather than a linear guide. Feel free to jump around to sections that are more relevant to you.

In this guide, we’ll go over dozens of use cases such as:

- how to create (touch) an empty file

- how to convert a path to string

- getting the home directory

- creating new directories, doing it recursively, and dealing with issues when they

- getting the current working directory

- get the file extension from a filename

- get the parent directory of a file or script

- read and write text or binary files

- how to delete files

- how create nested directories

- how to list all files and folders in a directory

- how to list all subdirectories recursively

- how to remove a directory along with its contents

I hope you enjoy!

Table of contents

- What is

pathlibin Python? - The anatomy of a

pathlib.Path - How to convert a path to string

- How to join a path by adding parts or other paths

- Working with directories using

pathlib- How to get the current working directory (cwd) with

pathlib - How to get the home directory with

pathlib - How to expand the initial path component with

Path.expanduser() - How to list all files and directories

- Using

isdirto list only the directories - Getting a list of all subdirectories in the current directory recursively

- How to recursively iterate through all files

- How to change directories with Python pathlib

- How to delete directories with

pathlib - How to remove a directory along with its contents with

pathlib

- How to get the current working directory (cwd) with

- Working with files using

pathlib- How to touch a file and create parent directories

- How to get the filename from path

- How to get the file extension from a filename using

pathlib - How to open a file for reading with

pathlib - How to read text files with

pathlib - How to read JSON files from path with

pathlib - How to write a text file with

pathlib - How to copy files with

pathlib - How to delete a file with

pathlib - How to delete all files in a directory with

pathlib - How to rename a file using

pathlib - How to get the parent directory of a file with

pathlib

- Conclusion

What is pathlib in Python?

pathlib is a Python module created to make it easier to work with paths in a file system. This module debuted in Python 3.4 and was proposed by the PEP 428.

Prior to Python 3.4, the os module from the standard library was the go to module to handle paths. os provides several functions that manipulate paths represented as plain Python strings. For example, to join two paths using os, one can use theos.path.join function.

>>> import os

>>> os.path.join('/home/user', 'projects')

'/home/user/projects'

>>> os.path.expanduser('~')

'C:\\Users\\Miguel'

>>> home = os.path.expanduser('~')

>>> os.path.join(home, 'projects')

'C:\\Users\\Miguel\\projects'

Representing paths as strings encourages inexperienced Python developers to perform common path operations using string method. For example, joining paths with + instead of using os.path.join(), which can lead to subtle bugs and make the code hard to reuse across multiple platforms.

Moreover, if you want the path operations to be platform agnostic, you will need multiple calls to various os functions such as os.path.dirname(), os.path.basename(), and others.

In an attempt to fix these issues, Python 3.4 incorporated the pathlib module. It provides a high-level abstraction that works well under POSIX systems, such as Linux as well as Windows. It abstracts way the path’s representation and provides the operations as methods.

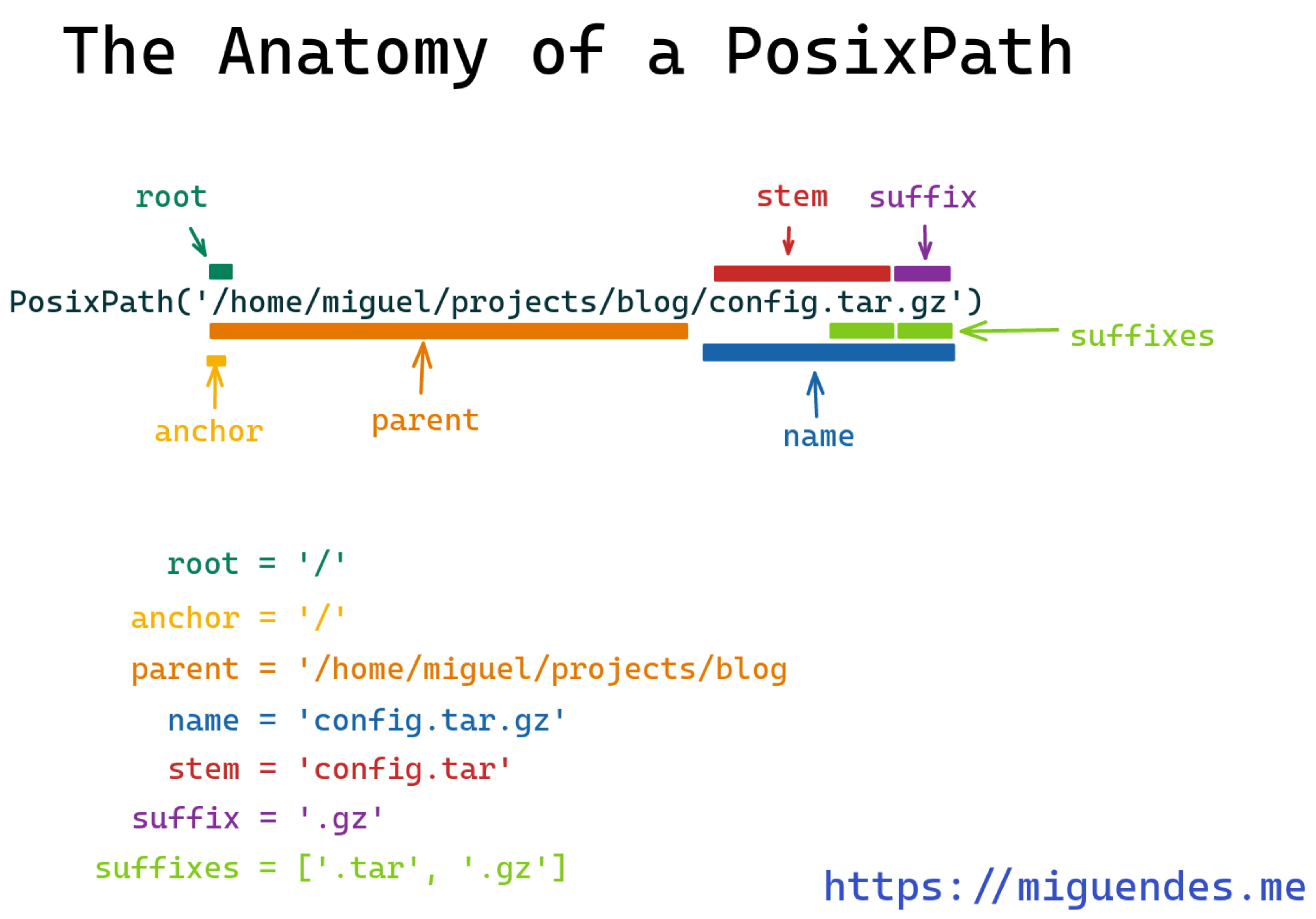

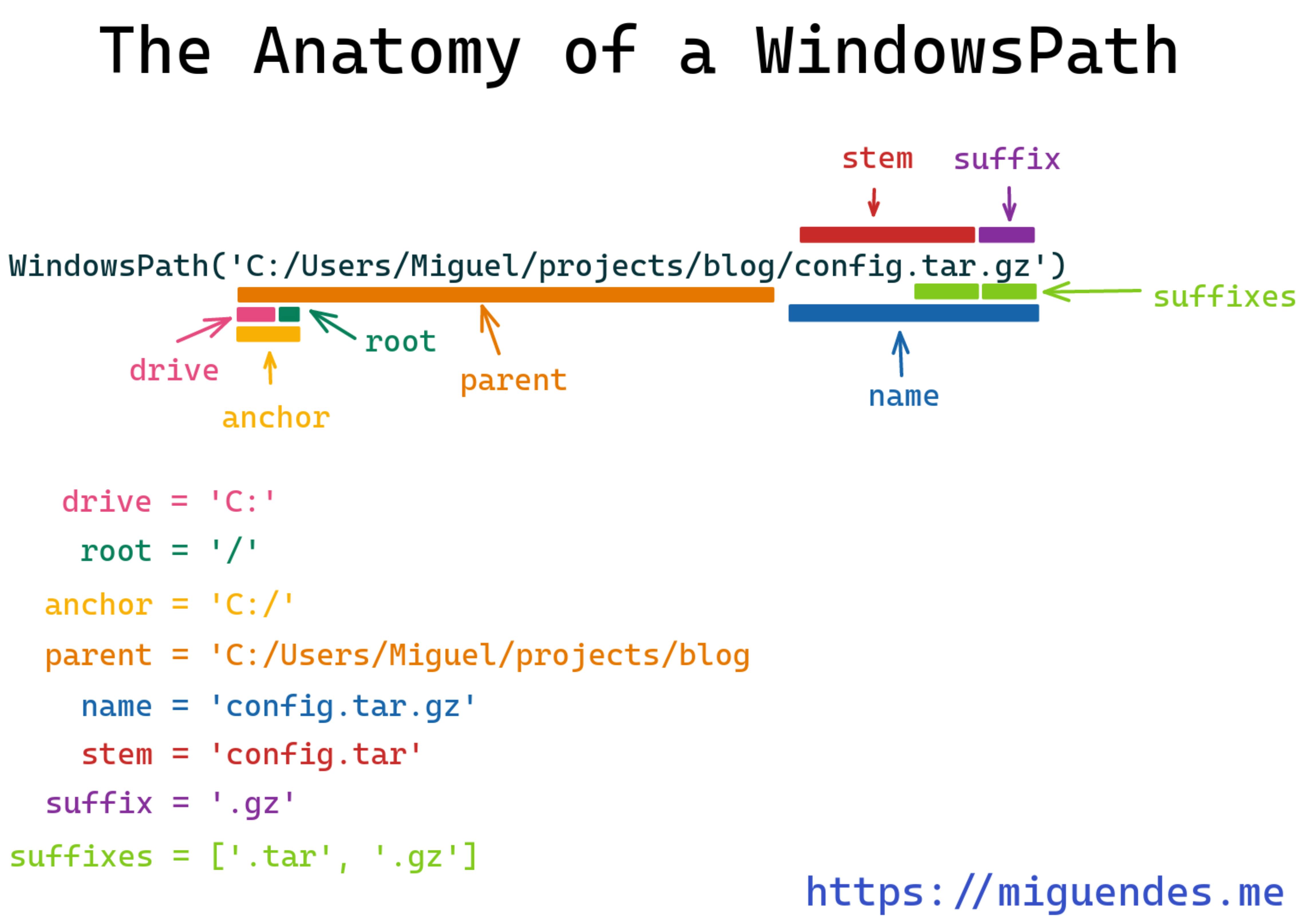

The anatomy of a pathlib.Path

To make it easier to understand the basics components of a Path, in this section we’ll their basic components.

>>> from pathlib import Path

>>> path = Path('/home/miguel/projects/blog/config.tar.gz')

>>> path.drive

'/'

>>> path.root

'/'

>>> path.anchor

'/'

>>> path.parent

PosixPath('/home/miguel/projects/blog')

>>> path.name

'config.tar.gz'

>>> path.stem

'config.tar'

>>> path.suffix

'.gz'

>>> path.suffixes

['.tar', '.gz']

>>> from pathlib import Path

>>> path = Path(r'C:/Users/Miguel/projects/blog/config.tar.gz')

>>> path.drive

'C:'

>>> path.root

'/'

>>> path.anchor

'C:/'

>>> path.parent

WindowsPath('C:/Users/Miguel/projects/blog')

>>> path.name

'config.tar.gz'

>>> path.stem

'config.tar'

>>> path.suffix

'.gz'

>>> path.suffixes

['.tar', '.gz']

How to convert a path to string

pathlib implements the magic __str__ method, and we can use it convert a path to string. Having this method implemented means you can get its string representation by passing it to the str constructor, like in the example below.

>>> from pathlib import Path

>>> path = Path('/home/miguel/projects/tutorial')

>>> str(path)

'/home/miguel/projects/tutorial'

>>> repr(path)

"PosixPath('/home/miguel/projects/blog/config.tar.gz')"

The example above illustrates a PosixPath, but you can also convert a WindowsPath to string using the same mechanism.

>>> from pathlib import Path

>>> path = Path(r'C:/Users/Miguel/projects/blog/config.tar.gz')

# when we convert a WindowsPath to string, Python adds backslashes

>>> str(path)

'C:\\Users\\Miguel\\projects\\blog\\config.tar.gz'

# whereas repr returns the path with forward slashes as it is represented on Windows

>>> repr(path)

"WindowsPath('C:/Users/Miguel/projects/blog/config.tar.gz')"

How to join a path by adding parts or other paths

One of the things I like the most about pathlib is how easy it is to join two or more paths, or parts. There are three main ways you can do that:

- you can pass all the individual parts of a path to the constructor

- use the

.joinpathmethod - use the

/operator

>>> from pathlib import Path

# pass all the parts to the constructor

>>> Path('.', 'projects', 'python', 'source')

PosixPath('projects/python/source')

# Using the / operator to join another path object

>>> Path('.', 'projects', 'python') / Path('source')

PosixPath('projects/python/source')

# Using the / operator to join another a string

>>> Path('.', 'projects', 'python') / 'source'

PosixPath('projects/python/source')

# Using the joinpath method

>>> Path('.', 'projects', 'python').joinpath('source')

PosixPath('projects/python/source')

On Windows, Path returns a WindowsPath instead, but it works the same way as in Linux.

>>> Path('.', 'projects', 'python', 'source')

WindowsPath('projects/python/source')

>>> Path('.', 'projects', 'python') / Path('source')

WindowsPath('projects/python/source')

>>> Path('.', 'projects', 'python') / 'source'

WindowsPath('projects/python/source')

>>> Path('.', 'projects', 'python').joinpath('source')

WindowsPath('projects/python/source')

Working with directories using pathlib

In this section, we’ll see how we can traverse, or walk, through directories with pathlib. And when it comes to navigating folders, there many things we can do, such as:

- getting the current working directory

- getting the home directory

- expanding the home directory

- creating new directories, doing it recursively, and dealing with issues when they already exist

- how create nested directories

- listing all files and folders in a directory

- listing only folders in a directory

- listing only the files in a directory

- getting the number of files in a directory

- listing all subdirectories recursively

- listing all files in a directory and subdirectories recursively

- recursively listing all files with a given extension or pattern

- changing current working directories

- removing an empty directory

- removing a directory along with its contents

How to get the current working directory (cwd) with pathlib

The pathlib module provides a classmethod Path.cwd() to get the current working directory in Python. It returns a PosixPath instance on Linux, or other Unix systems such as macOS or OpenBSD. Under the hood, Path.cwd() is just a wrapper for the classic os.getcwd().

>>> from pathlib import Path

>>> Path.cwd()

PosixPath('/home/miguel/Desktop/pathlib')

On Windows, it returns a WindowsPath.

>>> from pathlib import Path

>>> Path.cwd()

>>> WindowsPath('C:/Users/Miguel/pathlib')

You can also print it by converting it to string using a f-string, for example.

>>> from pathlib import Path

>>> print(f'This is the current directory: {Path.cwd()}')

This is the current directory: /home/miguel/Desktop/pathlib

PS: If you

How to get the home directory with pathlib

When pathlib arrived in Python 3.4, a Path had no method for navigating to the home directory. This changed on Python 3.5, with the inclusion of the Path.home() method.

In Python 3.4, one has to use os.path.expanduser, which is awkward and unintuitive.

# In python 3.4

>>> import pathlib, os

>>> pathlib.Path(os.path.expanduser("~"))

PosixPath('/home/miguel')

From Python 3.5 onwards, you just call Path.home().

# In Python 3.5+

>>> import pathlib

>>> pathlib.Path.home()

PosixPath('/home/miguel')

Path.home() also works well on Windows.

>>> import pathlib

>>> pathlib.Path.home()

WindowsPath('C:/Users/Miguel')

How to expand the initial path component with Path.expanduser()

In Unix systems, the home directory can be expanded using ~ ( tilde symbol). For example, this allows us to represent full paths like this: /home/miguel/Desktop as just: ~/Desktop/.

>>> from pathlib import Path

>>> path = Path('~/Desktop/')

>>> path.expanduser()

PosixPath('/home/miguel/Desktop')

Despite being more popular on Unix systems, this representation also works on Windows.

>>> path = Path('~/projects')

>>> path.expanduser()

WindowsPath('C:/Users/Miguel/projects')

>>> path.expanduser().exists()

True

What’s the opposite of

os.path.expanduser()?

Unfortunately, the pathlib module doesn’t have any method to do the inverse operation. If you want to condense the expanded path back to its shorter version, you need to get the path relative to your home directory using Path.relative_to, and place the ~ in front of it.

>>> from pathlib import Path

>>> path = Path('~/Desktop/')

>>> expanded_path = path.expanduser()

>>> expanded_path

PosixPath('/home/miguel/Desktop')

>>> '~' / expanded_path.relative_to(Path.home())

PosixPath('~/Desktop')

Creating directories with pathlib

A directory is nothing more than a location for storing files and other directories, also called folders. pathlib.Path comes with a method to create new directories named Path.mkdir().

This method takes three arguments:

mode: Used to determine the file mode and access flagsparents: Similar to themkdir -pcommand in Unix systems. Default toFalsewhich means it raises errors if there’s the parent is missing, or if the directory is already created. When it’sTrue,pathlib.mkdircreates the missing parent directories.exist_ok: Defaults toFalseand raisesFileExistsErrorif the directory being created already exists. When you set it toTrue,pathlibignores the error if the last part of the path is not an existing non-directory file.

>>> from pathlib import Path

# lists all files and directories in the current folder

>>> list(Path.cwd().iterdir())

[PosixPath('/home/miguel/path/not_created_yet'),

PosixPath('/home/miguel/path/reports')]

# create a new path instance

>>> path = Path('new_directory')

# only the path instance has been created, but it doesn't exist on disk yet

>>> path.exists()

False

# create path on disk

>>> path.mkdir()

# now it exsists

>>> path.exists()

True

# indeed, it shows up

>>> list(Path.cwd().iterdir())

[PosixPath('/home/miguel/path/not_created_yet'),

PosixPath('/home/miguel/path/reports'),

PosixPath('/home/miguel/path/new_directory')]

Creating a directory that already exists

When you have a directory path and it already exists, Python raises FileExistsError if you call Path.mkdir() on it. In the previous section, we briefly mentioned that this happens because by default the exist_ok argument is set to False.

>>> from pathlib import Path

>>> list(Path.cwd().iterdir())

[PosixPath('/home/miguel/path/not_created_yet'),

PosixPath('/home/miguel/path/reports'),

PosixPath('/home/miguel/path/new_directory')]

>>> path = Path('new_directory')

>>> path.exists()

True

>>> path.mkdir()

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

FileExistsError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-25-4b7d1fa6f6eb> in <module>

----> 1 path.mkdir()

~/.pyenv/versions/3.9.4/lib/python3.9/pathlib.py in mkdir(self, mode, parents, exist_ok)

1311 try:

-> 1312 self._accessor.mkdir(self, mode)

1313 except FileNotFoundError:

1314 if not parents or self.parent == self:

FileExistsError: [Errno 17] File exists: 'new_directory'

To create a folder that already exists, you need to set exist_ok to True. This is useful if you don’t want to check using if‘s or deal with exceptions, for example. Another benefit is that is the directory is not empty, pathlib won’t override it.

>>> path = Path('new_directory')

>>> path.exists()

True

>>> path.mkdir(exist_ok=True)

>>> list(Path.cwd().iterdir())

[PosixPath('/home/miguel/path/not_created_yet'),

PosixPath('/home/miguel/path/reports'),

PosixPath('/home/miguel/path/new_directory')]

>>> (path / 'new_file.txt').touch()

>>> list(path.iterdir())

[PosixPath('new_directory/new_file.txt')]

>>> path.mkdir(exist_ok=True)

# the file is still there, pathlib didn't overwrote it

>>> list(path.iterdir())

[PosixPath('new_directory/new_file.txt')]

How to create parent directories recursively if not exists

Sometimes you might want to create not only a single directory but also a parent and a subdirectory in one go.

The good news is that Path.mkdir() can handle situations like this well thanks to its parents argument. When parents is set to True, pathlib.mkdir creates the missing parent directories; this behavior is similar to the mkdir -p command in Unix systems.

>>> from pathlib import Path

>>> path = Path('new_parent_dir/sub_dir')

>>> path.mkdir()

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

FileNotFoundError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-35-4b7d1fa6f6eb> in <module>

----> 1 path.mkdir()

~/.pyenv/versions/3.9.4/lib/python3.9/pathlib.py in mkdir(self, mode, parents, exist_ok)

1311 try:

-> 1312 self._accessor.mkdir(self, mode)

1313 except FileNotFoundError:

1314 if not parents or self.parent == self:

FileNotFoundError: [Errno 2] No such file or directory: 'new_parent_dir/sub_dir'

>>> path.mkdir(parents=True)

>>> path.exists()

True

>>> path.parent

PosixPath('new_parent_dir')

>>> path

PosixPath('new_parent_dir/sub_dir')

How to list all files and directories

There are many ways you can list files in a directory with Python’s pathlib. We’ll see each one in this section.

To list all files in a directory, including other directories, you can use the Path.iterdir() method. For performance reasons, it returns a generator that you can either use to iterate over it, or just convert to a list for convenience.

>>> from pathlib import Path

>>> path = Path('/home/miguel/projects/pathlib')

>>> list(path.iterdir())

[PosixPath('/home/miguel/projects/pathlib/script.py'),

PosixPath('/home/miguel/projects/pathlib/README.md'),

PosixPath('/home/miguel/projects/pathlib/tests'),

PosixPath('/home/miguel/projects/pathlib/src')]

Using isdir to list only the directories

We’ve seen that iterdir returns a list of Paths. To list only the directories in a folder, you can use the Path.is_dir() method. The example below will get all the folder names inside the directory.

⚠️ WARNING: This example only lists the immediate subdirectories in Python. In the next subsection, we’ll see how to list all subdirectories.

>>> from pathlib import Path

>>> path = Path('/home/miguel/projects/pathlib')

>>> [p for p in path.iterdir() if p.is_dir()]

[PosixPath('/home/miguel/projects/pathlib/tests'),

PosixPath('/home/miguel/projects/pathlib/src')]

Getting a list of all subdirectories in the current directory recursively

In this section, we’ll see how to navigate in directory and subdirectories. This time we’ll use another method from pathlib.Path named glob.

>>> from pathlib import Path

>>> path = Path('/home/miguel/projects/pathlib')

>>> [p for p in path.glob('**/*') if p.is_dir()]

[PosixPath('/home/miguel/projects/pathlib/tests'),

PosixPath('/home/miguel/projects/pathlib/src'),

PosixPath('/home/miguel/projects/pathlib/src/dir')]

As you see, Path.glob will also print the subdirectory src/dir.

Remembering to pass '**/ to glob() is a bit annoying, but there’s a way to simplify this by using Path.rglob().

>>> from pathlib import Path

>>> path = Path('/home/miguel/projects/pathlib')

>>> [p for p in path.rglob('*') if p.is_dir()]

[PosixPath('/home/miguel/projects/pathlib/tests'),

PosixPath('/home/miguel/projects/pathlib/src'),

PosixPath('/home/miguel/projects/pathlib/src/dir')]

How to list only the files with is_file

Just as pathlib provides a method to check if a path is a directory, it also provides one to check if a path is a file. This method is called Path.is_file(), and you can use to filter out the directories and print all file names in a folder.

>>> from pathlib import Path

>>> path = Path('/home/miguel/projects/pathlib')

>>> [p for p in path.iterdir() if p.is_file()]

[PosixPath('/home/miguel/projects/pathlib/script.py'),

PosixPath('/home/miguel/projects/pathlib/README.md')]

⚠️ WARNING: This example only lists the files inside the current directory. In the next subsection, we’ll see how to list all files inside the subdirectories as well.

Another nice use case is using Path.iterdir() to count the number of files inside a folder.

>>> from pathlib import Path

>>> path = Path('/home/miguel/projects/pathlib')

>>> len([p for p in path.iterdir() if p.is_file()])

2

How to recursively iterate through all files

In previous sections, we used Path.rglob() to list all directories recursively, we can do the same for files by filtering the paths using the Path.is_file() method.

>>> from pathlib import Path

>>> path = Path('/home/miguel/projects/pathlib')

>>> [p for p in path.rglob('*') if p.is_file()]

[PosixPath('/home/miguel/projects/pathlib/script.py'),

PosixPath('/home/miguel/projects/pathlib/README.md'),

PosixPath('/home/miguel/projects/pathlib/tests/test_script.py'),

PosixPath('/home/miguel/projects/pathlib/src/dir/walk.py')]

How to recursively list all files with a given extension or pattern

In the previous example, we list all files in a directory, but what if we want to filter by extension? For that, pathlib.Path has a method named match(), which returns True if matching is successful, and False otherwise.

In the example below, we list all .py files recursively.

>>> from pathlib import Path

>>> path = Path('/home/miguel/projects/pathlib')

>>> [p for p in path.rglob('*') if p.is_file() and p.match('*.py')]

[PosixPath('/home/miguel/projects/pathlib/script.py'),

PosixPath('/home/miguel/projects/pathlib/tests/test_script.py'),

PosixPath('/home/miguel/projects/pathlib/src/dir/walk.py')]

We can use the same trick for other kinds of files. For example, we might want to list all images in a directory or subdirectories.

>>> from pathlib import Path

>>> path = Path('/home/miguel/pictures')

>>> [p for p in path.rglob('*')

if p.match('*.jpeg') or p.match('*.jpg') or p.match('*.png')

]

[PosixPath('/home/miguel/pictures/dog.png'),

PosixPath('/home/miguel/pictures/london/sunshine.jpg'),

PosixPath('/home/miguel/pictures/london/building.jpeg')]

We can actually simplify it even further, we can use only Path.glob and Path.rglob to matching. (Thanks to u/laundmo and u/SquareRootsi for pointing out!)

>>> from pathlib import Path

>>> path = Path('/home/miguel/projects/pathlib')

>>> list(path.rglob('*.py'))

[PosixPath('/home/miguel/projects/pathlib/script.py'),

PosixPath('/home/miguel/projects/pathlib/tests/test_script.py'),

PosixPath('/home/miguel/projects/pathlib/src/dir/walk.py')]

>>> list(path.glob('*.py'))

[PosixPath('/home/miguel/projects/pathlib/script.py')]

>>> list(path.glob('**/*.py'))

[PosixPath('/home/miguel/projects/pathlib/script.py'),

PosixPath('/home/miguel/projects/pathlib/tests/test_script.py'),

PosixPath('/home/miguel/projects/pathlib/src/dir/walk.py')]

How to change directories with Python pathlib

Unfortunately, pathlib has no built-in method to change directories. However, it is possible to combine it with the os.chdir() function, and use it to change the current directory to a different one.

⚠️ WARNING: For versions prior to 3.6,

os.chdironly accepts paths as string.

>>> import pathlib

>>> pathlib.Path.cwd()

PosixPath('/home/miguel')

>>> target_dir = '/home'

>>> os.chdir(target_dir)

>>> pathlib.Path.cwd()

PosixPath('/home')

How to delete directories with pathlib

Deleting directories using pathlib depends on if the folder is empty or not. To delete an empty directory, we can use the Path.rmdir()method.

>>> from pathlib import Path

>>> path = Path('new_empty_dir')

>>> path.mkdir()

>>> path.exists()

True

>>> path.rmdir()

>>> path.exists()

False

If we put some file or other directory inside and try to delete, Path.rmdir() raises an error.

>>> from pathlib import Path

>>> path = Path('non_empty_dir')

>>> path.mkdir()

>>> (path / 'file.txt').touch()

>>> path

PosixPath('non_empty_dir')

>>> path.exists()

True

>>> path.rmdir()

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

OSError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-64-00bf20b27a59> in <module>

----> 1 path.rmdir()

~/.pyenv/versions/3.9.4/lib/python3.9/pathlib.py in rmdir(self)

1350 Remove this directory. The directory must be empty.

...

-> 1352 self._accessor.rmdir(self)

1353

1354 def lstat(self):

OSError: [Errno 39] Directory not empty: 'non_empty_dir'

Now, the question is: how to delete non-empty directories with pathlib?

This is what we’ll see next.

How to remove a directory along with its contents with pathlib

To delete a non-empty directory, we need to remove its contents, everything.

To do that with pathlib, we need to create a function that uses Path.iterdir() to walk or traverse the directory and:

- if the path is a file, we call

Path.unlink() - otherwise, we call the function recursively. When there are no more files, that is, when the folder is empty, just call

Path.rmdir()

Let’s use the following example of a non empty directory with nested folder and files in it.

$ tree /home/miguel/Desktop/blog/pathlib/sandbox/

/home/miguel/Desktop/blog/pathlib/sandbox/

├── article.txt

└── reports

├── another_nested

│ └── some_file.png

└── article.txt

2 directories, 3 files

To remove it we can use the following recursive function.

>>> from pathlib import Path

>>> def remove_all(root: Path):

for path in root.iterdir():

if path.is_file():

print(f'Deleting the file: {path}')

path.unlink()

else:

remove_all(path)

print(f'Deleting the empty dir: {root}')

root.rmdir()

Then, we invoke it for the root directory, inclusive.

>>> from pathlib import Path

>>> root = Path('/home/miguel/Desktop/blog/pathlib/sandbox')

>>> root

PosixPath('/home/miguel/Desktop/blog/pathlib/sandbox')

>>> root.exists()

True

>>> remove_all(root)

Deleting the file: /home/miguel/Desktop/blog/pathlib/sandbox/reports/another_nested/some_file.png

Deleting the empty dir: /home/miguel/Desktop/blog/pathlib/sandbox/reports/another_nested

Deleting the file: /home/miguel/Desktop/blog/pathlib/sandbox/reports/article.txt

Deleting the empty dir: /home/miguel/Desktop/blog/pathlib/sandbox/reports

Deleting the file: /home/miguel/Desktop/blog/pathlib/sandbox/article.txt

Deleting the empty dir: /home/miguel/Desktop/blog/pathlib/sandbox

>>> root

PosixPath('/home/miguel/Desktop/blog/pathlib/sandbox')

>>> root.exists()

False

I need to be honest, this solution works fine but it’s not the most appropriate one. pathlib is not suitable for these kind of operations.

As suggested by u/Rawing7 from reddit, a better approach is to use shutil.rmtree.

>>> from pathlib import Path

>>> import shutil

>>> root = Path('/home/miguel/Desktop/blog/pathlib/sandbox')

>>> root.exists()

True

>>> shutil.rmtree(root)

>>> root.exists()

False

Working with files

In this section, we’ll use pathlib to perform operations on a file, for example, we’ll see how we can:

- create new files

- copy existing files

- delete files with

pathlib - read and write files with

pathlib

Specifically, we’ll learn how to:

- create (touch) an empty file

- touch a file with timestamp

- touch a new file and create the parent directories if they don’t exist

- get the file name

- get the file extension from a filename

- open a file for reading

- read a text file

- read a JSON file

- read a binary file

- opening all the files in a folder

- write a text file

- write a JSON file

- write bytes data file

- copy an existing file to another directory

- delete a single file

- delete all files in a directory

- rename a file by changing its name, or by adding a new extension

- get the parent directory of a file or script

How to touch (create an empty) a file

pathlib provides a method to create an empty file named Path.touch(). This method is very handy when you need to create a placeholder file if it does not exist.

>>> from pathlib import Path

>>> Path('empty.txt').exists()

False

>>> Path('empty.txt').touch()

>>> Path('empty.txt').exists()

True

Touch a file with timestamp

To create a timestamped empty file, we first need to determine the timestamp format.

One way to do that is to use the time and datetime. First we define a date format, then we use the datetime module to create the datetime object. Then, we use the time.mktime to get back the timestamp.

Once we have the timestamp, we can just use f-strings to build the filename.

>>> import time, datetime

>>> s = '02/03/2021'

>>> d = datetime.datetime.strptime(s, "%d/%m/%Y")

>>> d

datetime.datetime(2021, 3, 2, 0, 0)

>>> d.timetuple()

time.struct_time(tm_year=2021, tm_mon=3, tm_mday=2, tm_hour=0, tm_min=0, tm_sec=0, tm_wday=1, tm_yday=61, tm_isdst=-1)

>>> time.mktime(d.timetuple())

1614643200.0

>>> int(time.mktime(d.timetuple()))

1614643200

>>> from pathlib import Path

>>> Path(f'empty_{int(time.mktime(d.timetuple()))}.txt').exists()

False

>>> Path(f'empty_{int(time.mktime(d.timetuple()))}.txt').touch()

>>> Path(f'empty_{int(time.mktime(d.timetuple()))}.txt').exists()

True

>>> str(Path(f'empty_{int(time.mktime(d.timetuple()))}.txt'))

'empty_1614643200.txt'

How to touch a file and create parent directories

Another common problem when creating empty files is to place them in a directory that doesn’t exist yet. The reason is that path.touch() only works if the directory exists. To illustrate that, let’s see an example.

>>> from pathlib import Path

>>> Path('path/not_created_yet/empty.txt')

PosixPath('path/not_created_yet/empty.txt')

>>> Path('path/not_created_yet/empty.txt').exists()

False

>>> Path('path/not_created_yet/empty.txt').touch()

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

FileNotFoundError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-24-177d43b041e9> in <module>

----> 1 Path('path/not_created_yet/empty.txt').touch()

~/.pyenv/versions/3.9.4/lib/python3.9/pathlib.py in touch(self, mode, exist_ok)

1302 if not exist_ok:

1303 flags |= os.O_EXCL

-> 1304 fd = self._raw_open(flags, mode)

1305 os.close(fd)

1306

~/.pyenv/versions/3.9.4/lib/python3.9/pathlib.py in _raw_open(self, flags, mode)

1114 as os.open() does.

...

-> 1116 return self._accessor.open(self, flags, mode)

1117

1118 # Public API

FileNotFoundError: [Errno 2] No such file or directory: 'path/not_created_yet/empty.txt'

If the target directory does not exist, pathlib raises FileNotFoundError. To fix that we need to create the directory first, the simplest way, as described in the «creating directories» section, is to use the Path.mkdir(parents=True, exist_ok=True). This method creates an empty directory including all parent directories.

>>> from pathlib import Path

>>> Path('path/not_created_yet/empty.txt').exists()

False

# let's create the empty folder first

>>> folder = Path('path/not_created_yet/')

# it doesn't exist yet

>>> folder.exists()

False

# create it

>>> folder.mkdir(parents=True, exist_ok=True)

>>> folder.exists()

True

# the folder exists, but we still need to create the empty file

>>> Path('path/not_created_yet/empty.txt').exists()

False

# create it as usual using pathlib touch

>>> Path('path/not_created_yet/empty.txt').touch()

# verify it exists

>>> Path('path/not_created_yet/empty.txt').exists()

True

How to get the filename from path

A Path comes with not only method but also properties. One of them is the Path.name, which as the name implies, returns the filename of the path. This property ignores the parent directories, and return only the file name including the extension.

>>> from pathlib import Path

>>> picture = Path('/home/miguel/Desktop/profile.png')

>>> picture.name

'profile.png'

How to get the filename without the extension

Sometimes, you might need to retrieve the file name without the extension. A natural way of doing this would be splitting the string on the dot. However, pathlib.Path comes with another helper property named Path.stem, which returns the final component of the path, without the extension.

>>> from pathlib import Path

>>> picture = Path('/home/miguel/Desktop/profile.png')

>>> picture.stem

'profile'

How to get the file extension from a filename using pathlib

If the Path.stem property returns the filename excluding the extension, how can we do the opposite? How to retrieve only the extension?

We can do that using the Path.suffix property.

>>> from pathlib import Path

>>> picture = Path('/home/miguel/Desktop/profile.png')

>>> picture.suffix

'.png'

Some files, such as .tar.gz has two parts as extension, and Path.suffix will return only the last part. To get the whole extension, you need the property Path.suffixes.

This property returns a list of all suffixes for that path. We can then use it to join the list into a single string.

>>> backup = Path('/home/miguel/Desktop/photos.tar.gz')

>>> backup.suffix

'.gz'

>>> backup.suffixes

['.tar', '.gz']

>>> ''.join(backup.suffixes)

'.tar.gz'

How to open a file for reading with pathlib

Another great feature from pathlib is the ability to open a file pointed to by the path. The behavior is similar to the built-in open() function. In fact, it accepts pretty much the same parameters.

>>> from pathlib import Path

>>> p = Path('/home/miguel/Desktop/blog/pathlib/recipe.txt')

# open the file

>>> f = p.open()

# read it

>>> lines = f.readlines()

>>> print(lines)

['1. Boil water. \n', '2. Warm up teapot. ...\n', '3. Put tea into teapot and add hot water.\n', '4. Cover teapot and steep tea for 5 minutes.\n', '5. Strain tea solids and pour hot tea into tea cups.\n']

# then make sure to close the file descriptor

>>> f.close()

# or use a context manager, and read the file in one go

>>> with p.open() as f:

lines = f.readlines()

>>> print(lines)

['1. Boil water. \n', '2. Warm up teapot. ...\n', '3. Put tea into teapot and add hot water.\n', '4. Cover teapot and steep tea for 5 minutes.\n', '5. Strain tea solids and pour hot tea into tea cups.\n']

# you can also read the whole content as string

>>> with p.open() as f:

content = f.read()

>>> print(content)

1. Boil water.

2. Warm up teapot. ...

3. Put tea into teapot and add hot water.

4. Cover teapot and steep tea for 5 minutes.

5. Strain tea solids and pour hot tea into tea cups.

How to read text files with pathlib

In the previous section, we used the Path.open() method and file.read() function to read the contents of the text file as a string. Even though it works just fine, you still need to close the file or using the with keyword to close it automatically.

pathlib comes with a .read_text() method that does that for you, which is much more convenient.

>>> from pathlib import Path

# just call '.read_text()', no need to close the file

>>> content = p.read_text()

>>> print(content)

1. Boil water.

2. Warm up teapot. ...

3. Put tea into teapot and add hot water.

4. Cover teapot and steep tea for 5 minutes.

5. Strain tea solids and pour hot tea into tea cups.

The file is opened and then closed. The optional parameters have the same meaning as in open(). pathlib docs

How to read JSON files from path with pathlib

A JSON file a nothing more than a text file structured according to the JSON specification. To read a JSON, we can open the path for reading—as we do for text files—and use json.loads() function from the the json module.

>>> import json

>>> from pathlib import Path

>>> response = Path('./jsons/response.json')

>>> with response.open() as f:

resp = json.load(f)

>>> resp

{'name': 'remi', 'age': 28}

How to read binary files with pathlib

At this point, if you know how to read a text file, then you reading binary files will be easy. We can do this two ways:

- with the

Path.open()method passing the flagsrb - with the

Path.read_bytes()method

Let’s start with the first method.

>>> from pathlib import Path

>>> picture = Path('/home/miguel/Desktop/profile.png')

# open the file

>>> f = picture.open()

# read it

>>> image_bytes = f.read()

>>> print(image_bytes)

b'\x89PNG\r\n\x1a\n\x00\x00\x00\rIHDR\x00\x00\x01R\x00\x00\x01p\x08\x02\x00\x00\x00e\xd3d\x85\x00\x00\x00\x03sBIT\x08\x08\x08\xdb\xe1O\xe0\x00\x00\x00\x10tEXtSoftware\x00Shutterc\x82\xd0\t\x00\x00 \x00IDATx\xda\xd4\xbdkw\x1cY\x92\x1ch\xe6~#2\x13\xe0\xa3\xaa\xbbg

... [OMITTED] ....

0e\xe5\x88\xfc\x7fa\x1a\xc2p\x17\xf0N\xad\x00\x00\x00\x00IEND\xaeB`\x82'

# then make sure to close the file descriptor

>>> f.close()

# or use a context manager, and read the file in one go

>>> with p.open('rb') as f:

image_bytes = f.read()

>>> print(image_bytes)

b'\x89PNG\r\n\x1a\n\x00\x00\x00\rIHDR\x00\x00\x01R\x00\x00\x01p\x08\x02\x00\x00\x00e\xd3d\x85\x00\x00\x00\x03sBIT\x08\x08\x08\xdb\xe1O\xe0\x00\x00\x00\x10tEXtSoftware\x00Shutterc\x82\xd0\t\x00\x00 \x00IDATx\xda\xd4\xbdkw\x1cY\x92\x1ch\xe6~#2\x13\xe0\xa3\xaa\xbbg

... [OMITTED] ....

0e\xe5\x88\xfc\x7fa\x1a\xc2p\x17\xf0N\xad\x00\x00\x00\x00IEND\xaeB`\x82'

And just like Path.read_text(), pathlib comes with a .read_bytes() method that can open and close the file for you.

>>> from pathlib import Path

# just call '.read_bytes()', no need to close the file

>>> picture = Path('/home/miguel/Desktop/profile.png')

>>> picture.read_bytes()

b'\x89PNG\r\n\x1a\n\x00\x00\x00\rIHDR\x00\x00\x01R\x00\x00\x01p\x08\x02\x00\x00\x00e\xd3d\x85\x00\x00\x00\x03sBIT\x08\x08\x08\xdb\xe1O\xe0\x00\x00\x00\x10tEXtSoftware\x00Shutterc\x82\xd0\t\x00\x00 \x00IDATx\xda\xd4\xbdkw\x1cY\x92\x1ch\xe6~#2\x13\xe0\xa3\xaa\xbbg

... [OMITTED] ....

0e\xe5\x88\xfc\x7fa\x1a\xc2p\x17\xf0N\xad\x00\x00\x00\x00IEND\xaeB`\x82'

How to open all files in a directory in Python

Let’s image you need a Python script to search all files in a directory and open them all. Maybe you want to filter by extension, or you want to do it recursively. If you’ve been following this guide from the beginning, you now know how to use the Path.iterdir() method.

To open all files in a directory, we can combine Path.iterdir() with Path.is_file().

>>> import pathlib

>>> for i in range(2):

print(i)

# we can use iterdir to traverse all paths in a directory

>>> for path in pathlib.Path("my_images").iterdir():

# if the path is a file, then we open it

if path.is_file():

with path.open(path, "rb") as f:

image_bytes = f.read()

load_image_from_bytes(image_bytes)

If you need to do it recursively, we can use Path.rglob() instead of Path.iterdir().

>>> import pathlib

# we can use rglob to walk nested directories

>>> for path in pathlib.Path("my_images").rglob('*'):

# if the path is a file, then we open it

if path.is_file():

with path.open(path, "rb") as f:

image_bytes = f.read()

load_image_from_bytes(image_bytes)

How to write a text file with pathlib

In previous sections, we saw how to read text files using Path.read_text().

To write a text file to disk, pathlib comes with a Path.write_text(). The benefits of using this method is that it writes the data and close the file for you, and the optional parameters have the same meaning as in open().

⚠️ WARNING: If you open an existing file,

Path.write_text()will overwrite it.

>>> import pathlib

>>> file_path = pathlib.Path('/home/miguel/Desktop/blog/recipe.txt')

>>> recipe_txt = '''

1. Boil water.

2. Warm up teapot. ...

3. Put tea into teapot and add hot water.

4. Cover teapot and steep tea for 5 minutes.

5. Strain tea solids and pour hot tea into tea cups.

'''

>>> file_path.exists()

False

>>> file_path.write_text(recipe_txt)

180

>>> content = file_path.read_text()

>>> print(content)

1. Boil water.

2. Warm up teapot. ...

3. Put tea into teapot and add hot water.

4. Cover teapot and steep tea for 5 minutes.

5. Strain tea solids and pour hot tea into tea cups.

How to write JSON files to path with pathlib

Python represents JSON objects as plain dictionaries, to write them to a file as JSON using pathlib, we need to combine the json.dump function and Path.open(), the same way we did to read a JSON from disk.

>>> import json

>>> import pathlib

>>> resp = {'name': 'remi', 'age': 28}

>>> response = pathlib.Path('./response.json')

>>> response.exists()

False

>>> with response.open('w') as f:

json.dump(resp, f)

>>> response.read_text()

'{"name": "remi", "age": 28}'

How to write bytes data to a file

To write bytes to a file, we can use either Path.open() method passing the flags wb or Path.write_bytes() method.

>>> from pathlib import Path

>>> image_path_1 = Path('./profile.png')

>>> image_bytes = b'\x89PNG\r\n\x1a\n\x00\x00\x00\rIHDR\x00 [OMITTED] \x00I

END\xaeB`\x82'

>>> with image_path_1.open('wb') as f:

f.write(image_bytes)

>>> image_path_1.read_bytes()

b'\x89PNG\r\n\x1a\n\x00\x00\x00\rIHDR\x00 [OMITTED] \x00IEND\xaeB`\x82'

>>> image_path_2 = Path('./profile_2.png')

>>> image_path_2.exists()

False

>>> image_path_2.write_bytes(image_bytes)

37

>>> image_path_2.read_bytes()

b'\x89PNG\r\n\x1a\n\x00\x00\x00\rIHDR\x00 [OMITTED] \x00IEND\xaeB`\x82'

How to copy files with pathlib

pathlib cannot copy files. However, if we have a file represented by a path that doesn’t mean we can’t copy it. There are two different ways of doing that:

- using the

shutilmodule - using the

Path.read_bytes()andPath.write_bytes()methods

For the first alternative, we use the shutil.copyfile(src, dst) function and pass the source and destination path.

>>> import pathlib, shutil

>>> src = Path('/home/miguel/Desktop/blog/pathlib/sandbox/article.txt')

>>> src.exists()

True

>>> dst = Path('/home/miguel/Desktop/blog/pathlib/sandbox/reports/article.txt')

>>> dst.exists()

>>> False

>>> shutil.copyfile(src, dst)

PosixPath('/home/miguel/Desktop/blog/pathlib/sandbox/reports/article.txt')

>>> dst.exists()

True

>>> dst.read_text()

'This is \n\nan \n\ninteresting article.\n'

>>> dst.read_text() == src.read_text()

True

⚠️ WARNING:

shutilprior to Python 3.6 cannot handlePathinstances. You need to convert the path to string first.

The second method involves copying the whole file, then writing it to another destination.

>>> import pathlib, shutil

>>> src = Path('/home/miguel/Desktop/blog/pathlib/sandbox/article.txt')

>>> src.exists()

True

>>> dst = Path('/home/miguel/Desktop/blog/pathlib/sandbox/reports/article.txt')

>>> dst.exists()

False

>>> dst.write_bytes(src.read_bytes())

36

>>> dst.exists()

True

>>> dst.read_text()

'This is \n\nan \n\ninteresting article.\n'

>>> dst.read_text() == src.read_text()

True

⚠️ WARNING: This method will overwrite the destination path. If that’s a concern, it’s advisable either to check if the file exists first, or to open the file in writing mode using the

xflag. This flag will open the file exclusive creation, thus failing withFileExistsErrorif the file already exists.

Another downside of this approach is that it loads the file to memory. If the file is big, prefer shutil.copyfileobj. It supports buffering and can read the file in chunks, thus avoiding uncontrolled memory consumption.

>>> import pathlib, shutil

>>> src = Path('/home/miguel/Desktop/blog/pathlib/sandbox/article.txt')

>>> dst = Path('/home/miguel/Desktop/blog/pathlib/sandbox/reports/article.txt')

>>> if not dst.exists():

dst.write_bytes(src.read_bytes())

else:

print('File already exists, aborting...')

File already exists, aborting...

>>> with dst.open('xb') as f:

f.write(src.read_bytes())

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

FileExistsError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-25-1974c5808b1a> in <module>

----> 1 with dst.open('xb') as f:

2 f.write(src.read_bytes())

3

How to delete a file with pathlib

You can remove a file or symbolic link with the Path.unlink() method.

>>> from pathlib import Path

>>> Path('path/reports/report.csv').touch()

>>> path = Path('path/reports/report.csv')

>>> path.exists()

True

>>> path.unlink()

>>> path.exists()

False

As of Python 3.8, this method takes one argument named missing_ok. By default, missing_ok is set to False, which means it will raise an FileNotFoundError error if the file doesn’t exist.

>>> path = Path('path/reports/report.csv')

>>> path.exists()

False

>>> path.unlink()

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

FileNotFoundError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-6-8eea53121d7f> in <module>

----> 1 path.unlink()

~/.pyenv/versions/3.9.4/lib/python3.9/pathlib.py in unlink(self, missing_ok)

1342 try:

-> 1343 self._accessor.unlink(self)

1344 except FileNotFoundError:

1345 if not missing_ok:

FileNotFoundError: [Errno 2] No such file or directory: 'path/reports/report.csv'

# when missing_ok is True, no error is raised