Уровень сложностиСредний

Время на прочтение19 мин

Количество просмотров56K

Всем привет!

Мы — команда исследователей‑аналитиков киберугроз в компании R‑Vision. Одной из наших задач является исследование возможных альтернативных и дополнительных источников событий для более точного детектирования атак.

И сегодня мы рассмотрим тему мониторинга RPC (Remote Procedure Call, удаленный вызов процедур), а также разберем возможные варианты логирования Microsoft Remote Procedure Call (MS‑RPC), связанного с актуальными и популярными на сегодняшний день атаками.

Но преждем чем приступить, предлагаем ознакомиться с базовой работой RPC и с тем, на каких механизмах она основывается. В дальнейшем это поможет нам понять, какую информацию необходимо собирать и отслеживать при детектировании атак с использованием удаленного вызова процедур.

Что такое RPC?

Remote Procedure Call или «удаленный вызов процедур» представляет собой технологию межпроцессного взаимодействия IPC. Она позволяет программам вызывать функции и процедуры удаленно таким образом, как‑будто они представлены локально. В среде Windows используется проприетарный протокол от Microsoft — MS‑RPC, который является производным от технологии DCE/RPC (Distributed Computing Environment/ Remote Procedure Calls). Для упрощения понимания мы будем называть MS‑RPC просто RPC.

Службы RPC используются во множестве процессов в операционных системах Windows. Например, с их помощью можно удалённо изменять значения в реестре, создавать новые задачи и сервисы. На вызовах RPC построена значимая часть работы Active Directory: функции аутентификации в домене, репликация данных и многие другие вещи — список грандиозно большой.

В виду того, что RPC используется в Windows практически во всех процессах, по понятным причинам она является предметом особого интереса для атакующих. В тоже время RPC фигурирует в большом количестве популярных и опасных атак. К ним относится PetitPotam, с чьей помощью можно произвести атаку типа Relay на машинный аккаунт контроллера домена. Еще одна атака — DCSync, позволяющая скомпрометировать всех пользователей в домене при наличии учетной записи с высокими привилегиями. Кроме того, в арсенале атакующих есть еще и фреймворк Impacket, который может задействовать RPC для отправки вредоносных команд на удаленный сервер.

Все это говорит нам о важности понимания механизмов работы RPC, а также о необходимости её мониторинга.

Механизмы работы RPC

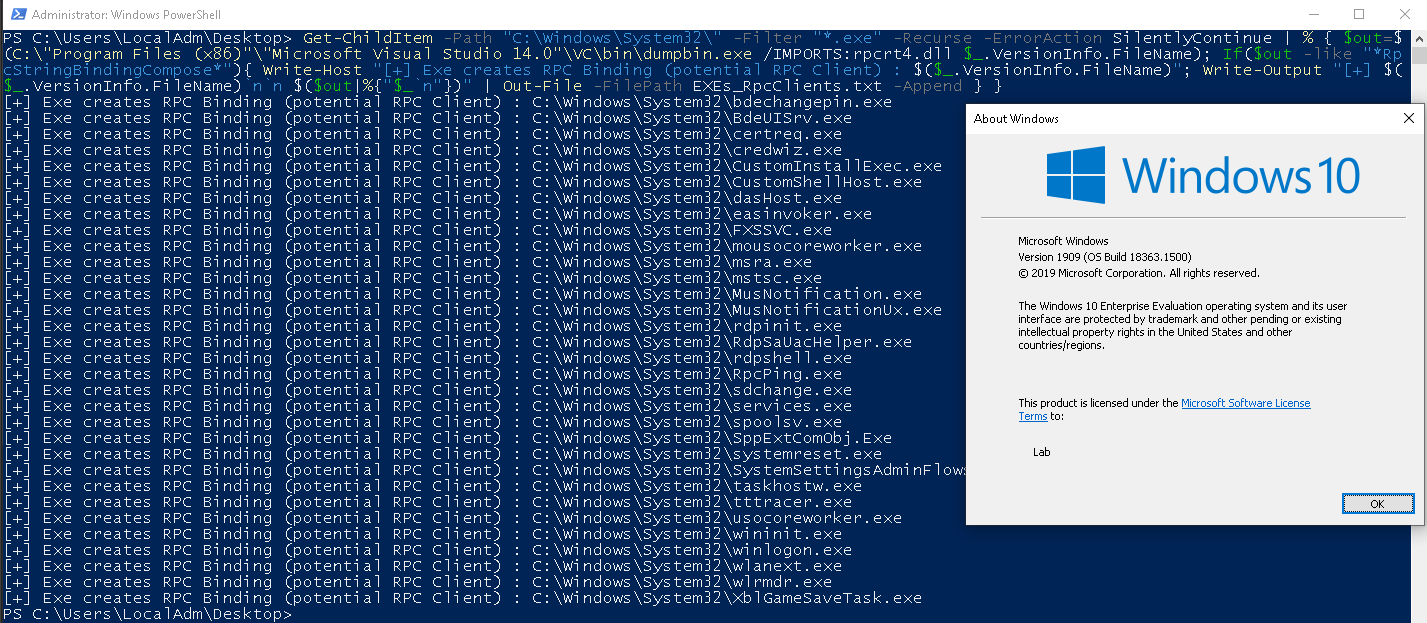

Изучение механизмов работы RPC мы начнем с краткого разбора сетевого трафика, поскольку протокол RPC в первую очередь является сетевым. На рисунке 1 мы видим подключение к удалённой машине: оно начинается с Bind запроса (выделен красным), после которого фигурирует второй Bind запрос (выделен синим). Первый используется для подключения к службе Endpoint Mapper (EPM), про него мы поговорим дальше. Второй инициирует подключение к самому RPC интерфейсу. После прохождения аутентификации устанавливается сессия, а уже дальше осуществляется вызов нужной функции и возвращение результата.

Эволюция, конечно, могла бы остановиться здесь, если бы для RPC применялись только протоколы TCP и UDP, но в Microsoft пошли немного дальше и применяют так называемую последовательность из протоколов. К ней мы вернемся позднее, а сейчас рассмотрим, что такое EPM.

Endpoint Mapper

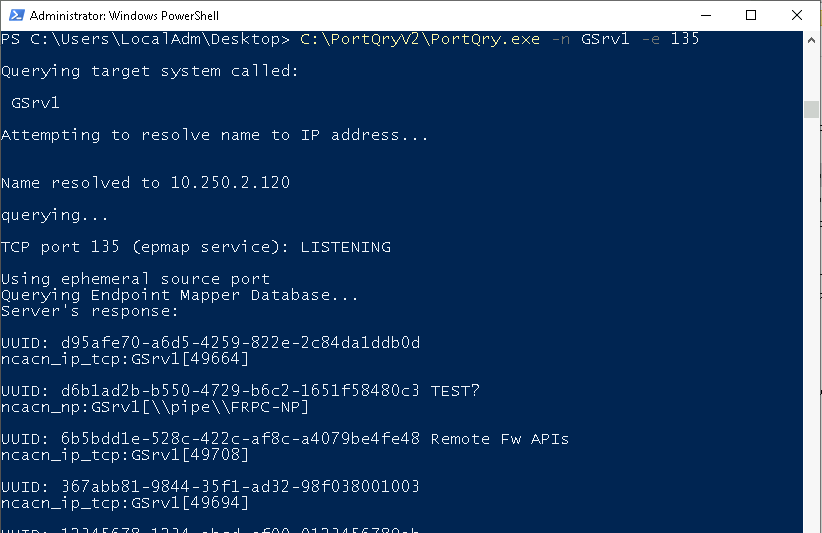

Одним из важных механизмов взаимодействия с RPC сервисами является служба Endpoint Mapper (EPM), расположенная на стороне сервера. Её главная задача помочь определить параметры дальнейшего подключения к нужному сервису для клиента. Сам EPM, как это ни странно, является таким же RPC сервисом, использующим для транспорта порты TCP/135 или TCP/593 (RPC over HTTP).

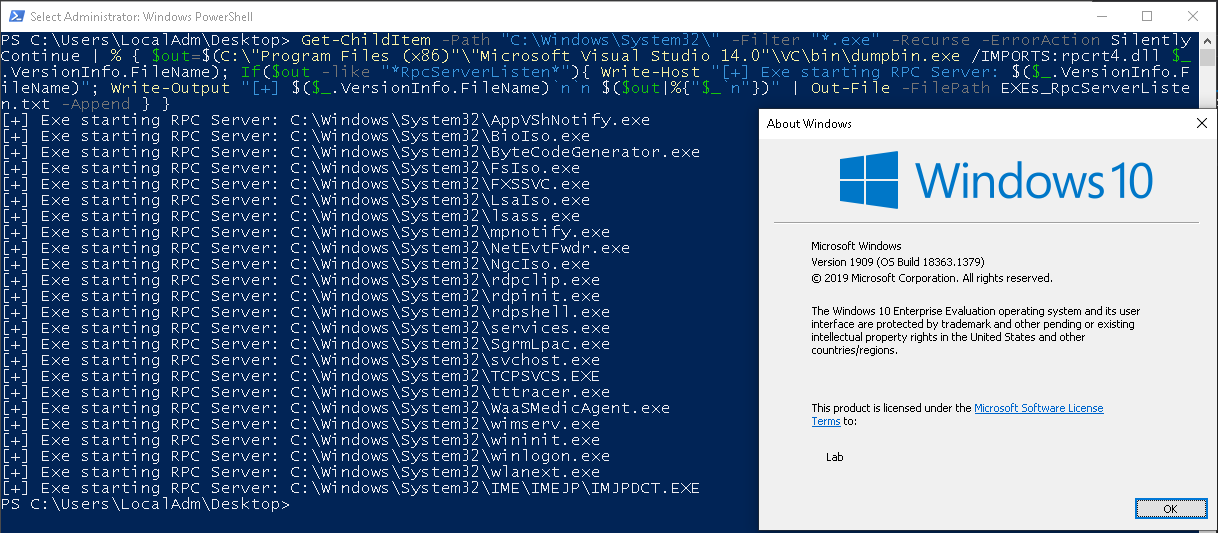

EPM‑cервис расположен на каждой Windows машине и содержит базу зарегистрированных RPC интерфейсов. За каждый из интерфейсов чаще всего отвечает свой исполняемый файл или динамически подгружаемая библиотека (DLL). Посмотреть список всех доступных интерфейсов можно с помощью утилиты rcpdump.py из упомянутого нами ранее фреймворка Impacket.

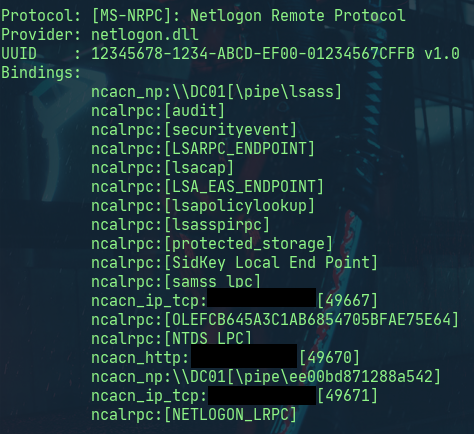

На рисунке 3 приведен пример вывода по одному из доступных интерфейсов.

Здесь мы можем увидеть:

-

Название интерфейса: Netlogon Remote Protocol;

-

Библиотеку провайдера, отвечающего за нужные нам функции: netlogon.dll;

-

Уникальный идентификатор интерфейса: UUID;

-

Список точек подключения к данному интерфейсу, которые записываются в формате:

"значение, отражающее последовательность протоколов":хост[порт]Отметим в приведенном выше интерфейсе два протокола:

-

ncalrpc — отражает локальное использование по протоколу LRPC;

-

ncacn_np — отражает подключение по именованному каналу Named Pipes (NPs). В связи с этим у него вместо порта указан путь.

Может возникнуть вполне резонный вопрос: всегда ли нужно обращаться к EPM? Нет, не всегда, так как существуют статические точки подключения, остающиеся неизменными. К ним, например, относится NPs \pipe\lsass.

Можно также посмотреть на RPC интерфейсы процессов не только снаружи, но и «изнутри». Они выглядят примерно так.

Что дальше?

После того как клиент определил куда он будет дальше подключаться, в процесс вступает сериализация данных. Если клиентом является Windows система, то эту работу будет выполнять компонент NDR (Network Data Representation). Он также отвечает за десериализацию данных со стороны RPC сервера. После чего данные попадают в качестве аргументов функции и другой информации для вызова этой самой функции в DLL библиотеку, ответственную за определённый RPC функционал. На финальном этапе функция выполняется, а её вывод передаётся обратно в RPC для отправки клиенту.

Протоколы в RPC

Разобравшись как работает RPC, подробнее изучим протоколы, которые активно эксплуатируются в интерфейсах RPC и, следовательно, доступны атакующему. И первым мы рассмотрим протокол Named Pipes (NPs).

Named Pipes

Данный протокол следует принципам передачи данных через чтение и запись: используя NPs можно записывать, а также сразу читать наименование и аргументы функций. Более того, это даже можно делать одновременно. NPs проще всего представлять в виде файлов: в Windows взаимодействие с ними происходит с помощью функций CreateFile, ReadFile, WriteFile, что в некоторой степени намекает нам на схожесть этих технологий. NPs выполняет роль интеграционного слоя между RPC и другими служебными компонентами.

Со стороны клиента NPs можно представить как точки подключения для выполнения какого‑то конкретного функционала. Например, точка подключения \pipe\svcctl направлена на управление службами на конечном устройстве. Однако Microsoft не всегда следует такому разделению. Так, при подключении к \pipe\lsass можно вызвать функции EFS сервиса, если передать корректный UUID при выполнении bind запроса.

На стороне сервера, на который происходит обращение, выполняется импорт библиотеки, отвечающий за EFS (C:\Windows\System32\efslsaext.dll) в процесс lsass. Стоит отметить, что у EFS существует свой собственный интерфейс \pipe\efsr.

Также EFS функционал может быть вызван с помощью других точек, например через samr или lsarpc, за каждым из которых стоит процесс lsass. Это в свою очередь наталкивает на мысль о некоторой «универсальности» процессов — интерфейсов, так как каждый процесс может импортировать нужную библиотеку и существует возможность вызывать функции любых других сервисов.

Перейдем к следующему протоколу — SMB.

SMB

Если отойти немного от протокола RPC и посмотреть на NPs отдельно, мы обнаружим, что NPs может вполне заменить RPC, так как первый исполняет функции удаленно даже без второго. Для этих целей он использует протокол SMB (Server Message Block). При этом фактически SMB нужен только для доступа к служебной директории IPC$, аббревиатура которой расшифровывается как Interprocess Communication. Через эту «папку» можно читать, записывать, но только NPs, что вполне в духе SMB, и вызывать таким образом удаленные функции.

LRPC

До этого мы говорили про протоколы, которые используются в удаленным вызове, но есть и локальный вариант RPC — протокол LRPC, у которого существует две трактовки: Local RPC или Lightweight RPC. Этот протокол предназначен только для локальных вызовов. Конечно, при использовании подключений по NPs или RPC на адрес localhost эффект будет тот же. Более того, некоторые программы так и делают, но для локальных вызовов LRPC работает куда быстрее и он удобнее в использовании. В выводе rpcdump.py мы его видели «зашифрованным» под ncalrpc. При этом LRPC работает поверх ALPC — еще одного протокола, о котором будет сказано чуть позже.

Но сначала про LPC.

LPC

LPC (Local Procedure Call) — также отвечает за механизм общения процессов в одной и той же системе. Данный протокол является недокументированным и используется (использовался) только внутри самой Microsoft. БОльшую часть информации об этом протоколе мы можем узнать исходя из работ реверс специалистов. Сторонний софт использует его не напрямую, а взаимодействует через документированный LRPC.

А теперь вернемся к ALPC.

ALPC

LPC — это все же устаревшая технология и в явном виде уже не используется. На смену ей пришел ALPC (Advanced Local Procedure Call), являющийся асинхронным и также недокументированным протоколом. Работает он по принципу клиент‑серверной модели. В качестве сервера выступает процесс, принимающий соединения на определённый порт. Порт для подключения открывается с помощью функции NtAlpcCreatePort. Любой процесс имеет возможность подключиться к этому порту в качестве клиента, используя функцию NtAlpcConnectPort. Один «процесс‑сервер» может взаимодействовать сразу с несколькими клиентами одновременно.

DCOM

Рассмотрим последний протокол, который фигурирует в RPC — DCOM, чья аббревиатура расшифровывается как Distributed COM. Фактически эта технология вызова COM‑интерфейсов удалённо. Тут нет больших отличий со стороны трафика, но есть различия в механизме вызова удаленных функций. DCOM не вызывает функции напрямую, а сначала инициализирует COM‑объект, функционал которого будет использовать. Концептуально это похоже на NPs с их разделением функционала на отдельные именованные каналы. Если рассматривать алгоритм общения клиента и сервера, то здесь не так много отличий от «чистого» RPC, но есть два исключения — вызов функций ISystemActivator и IDispatch.

Для вызова функции определённого COM объекта, такой объект сначала нужно вызвать, чтобы затем он «запустился»: загрузился в оперативную память и был доступен для работы. В локальном мире этим занимается COM интерфейс IUnknown. Он позволяет также узнать функции неизвестных COM интерфейсов для работы с ними.

При работе с DCOM ту же функцию выполняет ISystemActivator, позволяя обратиться к неизвестным DCOM интерфейсам, являющимися по сути теми же COM объектам, и работать с ними. ISystemActivator вызывается каждый раз при новом DCOM подключении.

Также IUnknown интерфейс дает возможность вызывать и другие функции COM объекта напрямую, фактически сводя всю работу с COM объектами до одной лишь функции IUnknown интерфейса. Тоже самое выполняет и интерфейс IDispatch для DCOM, позволяя выполнять любую функцию в мире DCOM через него. Поэтому, если мы взглянем на трафик, то увидим сначала вызов ISystemActivator, а потом только лишь обращения к IDispatch, вне зависимости от того какую DCOM функцию использует клиент.

Рассказывая про ALPC, мы упомянули, что эта технология используется только локально. Но это, конечно, не совсем правда, так как ALPC задействован чуть ли не во всех компонентах Windows. Поэтому, так или иначе, любое действие, в том числе и удалённое, будет прямо или косвенно применять ALPC. Это особенно интересно в контексте DCOM, потому что он напрямую использует ALPC на локальной машине, при этом будучи вызванным удалённым пользователем.

Схема вариантов RPC-подключений

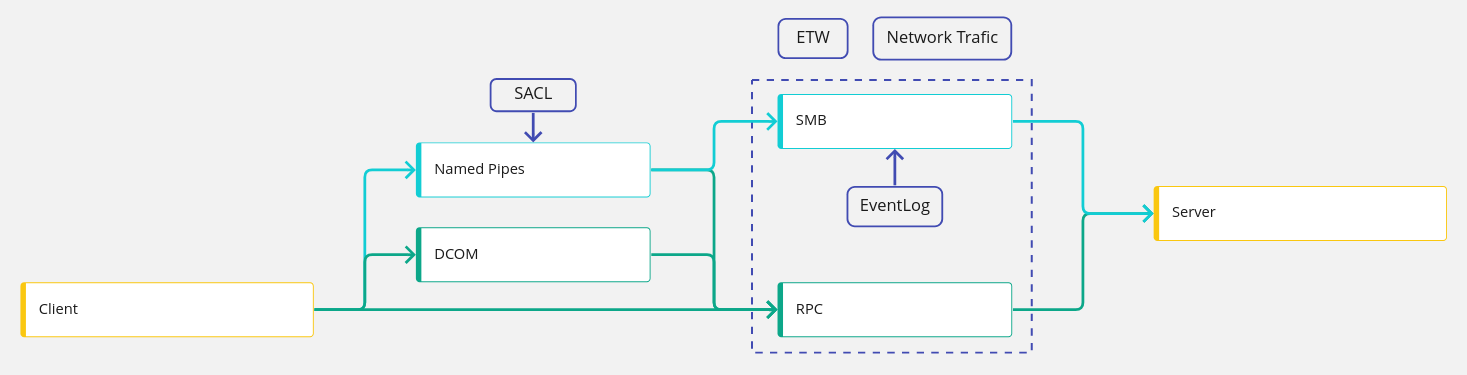

Подведем итог вышесказаного в виде схемы вариантов подключения к удалённой машине, отражающей возможные пути со стороны клиента, которые в том числе доступны и для атакующего. Как видим из рисунка 5, все не так просто.

Способы мониторинга

Разобравшись с вариантами RPC‑подключений, и, как следствие, с потенциально возможными действиями со стороны атакующего, рассмотрим, варианты мониторинга, которые нам может предоставить сама операционная система: ETW, журналы безопасности, SACL, RPC Filtering, RPC Firewall и сетевой трафик.

И начнем с технологии, на базе которой строится функционал для логирования событий в операционной системе Windows — Event Tracing for Windows (ETW).

Event Tracing for Windows

Event Tracing for Windows или сокращено ETW имеет множество, так называемых, провайдеров, которых в ОС более нескольких тысяч. Они позволяют отслеживать через события как отдельные технологии, так и конкретные процессы. Часть провайдеров формируют вполне понятные для обыденного пользователя события, другая же, бОльшая часть, используется исключительно только самой Microsoft для отладки.

ETW предоставляет возможность смотреть события вызовов RPC функций через стандартную оснастку Event Viewer. ETW провайдеры, связанные с RPC, представлены в таблице ниже.

Провайдеры, связанные с RPC

|

Название провайдера |

GUID |

|

Microsoft-Windows-RPC |

{6AD52B32-D609-4BE9-AE07-CE8DAE937E39} |

|

Microsoft-Windows-RPC-Events |

{F4AED7C7-A898-4627-B053-44A7CAA12FCD} |

|

Microsoft-Windows-RPC-FirewallManager |

{F997CD11-0FC9-4AB4-ACBA-BC742A4C0DD3} |

|

Microsoft-Windows-RPC-Proxy-LBS |

{272A979B-34B5-48EC-94F5-7225A59C85A0} |

|

Microsoft-Windows-RPCSS |

{D8975F88-7DDB-4ED0-91BF-3ADF48C48E0C} |

Саму настройку событий можно посмотреть здесь.

Настройка просмотра событий

Как ранее говорилось, мы можем увидеть события в оснастке Event Viewer. Для этого нам необходимо включить отображение события отладки (View Show → Analytic and Debug Log ), после чего появятся доступные к просмотру журналы событий, в том числе и RPC.

События, связанные с RPC будут доступны по пути Application and Services Logs → Microsoft → Windows → RPC, в журнале Debug.

Разбор событий

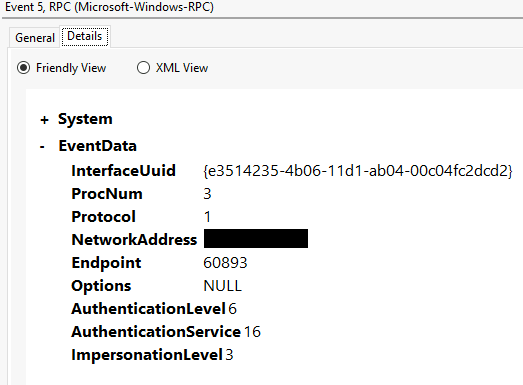

Теперь проведем разбор события на одном из примеров, показанных на рисунке 7.

В данном событии мы видим информацию об RPC запросе к именованному каналу \pipe\lsass по интерфейсу UUID 12 345 778–1234-abcd‑ef00–0 123 456 789ac и с номером процедуры (ProcNum / OpCode) — 34.

Переведем это событие с «машинного» языка: здесь мы фиксируем обращение к интерфейсу SAMR (Security Account Manager Remote). Атрибут Endpoint имеет значение \pipe\lsass, потому что SAMR интерфейс содержит в поле Named Pipe значение \pipe\lsass и конечное подключение производится к нему. Также виден протокол номер 2, что трактуется как NPs.

|

Поле |

«Сырое» значение |

Расшифровка |

|---|---|---|

|

InterfaceUuid |

2345778-1234-abcd-ef00-0123456789ac |

SAMR |

|

ProcNum |

34 |

SamrOpenUser |

|

Protocol |

2 |

Named Pipe |

Стоит отметить, что некоторые NPs, такие как srvsvc и wkssvc динамически меняют свои GUID номера и, как следствие, их нельзя идентифицировать по одному общеизвестному GUID, но это можно сделать через поле Endpoint, которое четко указывает на соответствующий интерфейс.

Рассмотрим другой пример: при выполнении атаки DCShadow, мы можем увидеть следующее событие в журнале (рисунок 9).

На этом рисунке можно увидеть подключение к интерфейсу DRSUAPI, который имеет GUID e3 514 235–4b06–11d1-ab04–00c04fc2dcd2, протокол (Protocol) 1 или его человеко‑читаемое имя ‑TCP, а также IP‑адрес, с которого было совершено подключение. Как и в предыдущем примере здесь отображен номер процедуры (ProcNum) — 3, который трактуется как репликация обновления из NC реплики.

Журнал безопасности

Политики аудита позволяют нам настроить сбор событий, которые относятся в Windows к событиям безопасности. Они фиксируют обращения к NPs через SMB и «папку» IPC$. Сразу отметим минус такого подхода: если, к примеру, клиент будет обращаться к NPs через RPC, а не IPC$, то в событиях мы этого не увидим.

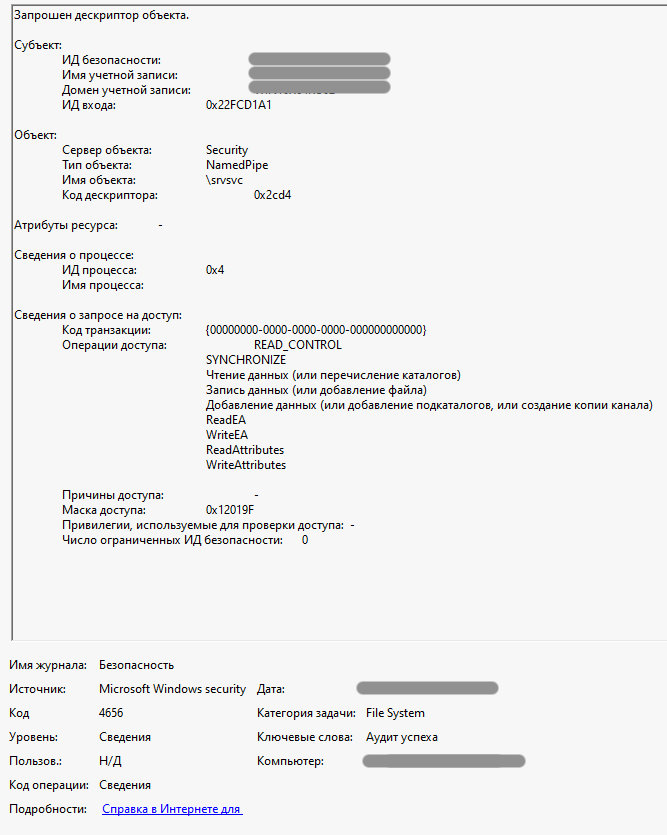

IPC$ — это системная папка общего доступа, с ее помощью мы можем логировать события подключения через политику Detailed File Share. Пример возможного события указан на рисунке 10 ниже.

События безопасности будут сформированы, если подключиться к NPs с именем srvsvc, как нам и показывает второй лог в разделе Сведение об общем ресурсе (Share Information) → Относительное имя конечного объекта (Relative Target Name). Как вы могли заметить, в данном событии не фиксируется номер процедуры (ProcNum), по которому можно было бы отследить что происходит.

System Access Control List

Для NPs также можно включить SACL (System Access Control List), чтобы фиксировать любые действия с ними. Пример события указан на рисунке 12.

Эти события практически идентичны тем, что мы получаем от политики аудита Detailed File Share. Поэтому гораздо проще включить политику, чем выставлять SACL повсеместно. Но включение SACL может помочь отслеживать подключение там, где оно происходит напрямую по RPC, при этом совершенно минуя SMB.

Выставлять SACL на NPs — не самая тривиальная задача, так как она не переживает перезагрузку машины и требует написания собственного кода, тем не менее является одним из вариантов проведения мониторинга.

Мы подготовили небольшой код, который может менять SACL на NPs.

Код C++ для выставления SACL

#include <aclapi.h>

#include <iostream>

BOOL SetPrivilege(

HANDLE hToken, // access token handle

LPCTSTR lpszPrivilege, // name of privilege to enable/disable

BOOL bEnablePrivilege // to enable or disable privilege

)

{

TOKEN_PRIVILEGES tp;

LUID luid;

if (!LookupPrivilegeValue(

NULL, // lookup privilege on local system

lpszPrivilege, // privilege to lookup

&luid)) // receives LUID of privilege

{

printf("LookupPrivilegeValue error: %u\n", GetLastError());

return FALSE;

}

tp.PrivilegeCount = 1;

tp.Privileges[0].Luid = luid;

if (bEnablePrivilege)

tp.Privileges[0].Attributes = SE_PRIVILEGE_ENABLED;

else

tp.Privileges[0].Attributes = 0;

// Enable the privilege or disable all privileges.

if (!AdjustTokenPrivileges(

hToken,

FALSE,

&tp,

sizeof(TOKEN_PRIVILEGES),

(PTOKEN_PRIVILEGES)NULL,

(PDWORD)NULL))

{

printf("AdjustTokenPrivileges error: %u\n", GetLastError());

return FALSE;

}

if (GetLastError() == ERROR_NOT_ALL_ASSIGNED)

{

printf("The token does not have the specified privilege. \n");

return FALSE;

}

return TRUE;

};

BOOL SetSecurityPrivilage(BOOL bEnablePrivilege) {

LPCTSTR lpszPrivilege = L"SeSecurityPrivilege";

HANDLE hToken;

// Open a handle to the access token for the calling process. That is this running program

if (!OpenProcessToken(GetCurrentProcess(), TOKEN_ADJUST_PRIVILEGES, &hToken)) {

printf("OpenProcessToken() error %u\n", GetLastError());

return FALSE;

}

// Call the user defined SetPrivilege() function to enable and set the needed privilege

if (!SetPrivilege(hToken, lpszPrivilege, bEnablePrivilege)) {

printf("Failed to adjust Privilege\n");

return FALSE;

}

return TRUE;

};

wchar_t *convertCharArrayToLPCWSTR(const char* charArray)

{

wchar_t* wString=new wchar_t[4096];

MultiByteToWideChar(CP_ACP, 0, charArray, -1, wString, 4096);

return wString;

}

int main(int argc, char* argv[])

{

LPCWSTR pipeName = NULL;

LPWCH groupName = NULL;

BOOL clrSACL = FALSE;

if (argc <= 1)

{

printf("%s\n", "Help page, do it like this:\nprog.exe -path \\\\.\\pipe\\lsass -name Everyone\nOr to clear the SACL use -clr\nIt sets both success and failure audit, by now it works only with pipes");

return 0;

}

// Argument parsing

for (int i = 0; i < argc; ++i)

{

if (strcmp(argv[i], "-path") == 0)

{

pipeName = convertCharArrayToLPCWSTR(argv[i + 1]);

}

if (strcmp(argv[i], "-name") == 0)

{

groupName = convertCharArrayToLPCWSTR(argv[i + 1]);

}

if (strcmp(argv[i], "-clr") == 0)

{

clrSACL = TRUE;

}

}

// Get Priv

if (!SetSecurityPrivilage(TRUE)) {

printf("Try to launch with Admin rights\n");

return 1;

}

// Open the pipe with ACCESS_SYSTEM_SECURITY, the only right which allows to edit SACL

HANDLE hPipe = CreateFile(pipeName, ACCESS_SYSTEM_SECURITY, 0, NULL, OPEN_EXISTING, NULL, NULL);

if (hPipe == INVALID_HANDLE_VALUE)

{

printf("%s\n%d\n", "Incorrect handle", GetLastError());

return 1;

}

// Just clear SACL and get out

if (clrSACL)

{

if (SetSecurityInfo(hPipe, SE_KERNEL_OBJECT, SACL_SECURITY_INFORMATION, NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL) != ERROR_SUCCESS)

{

printf("%s\n%d\n", "SetSecurityInfo", GetLastError());

return 1;

}

printf("%s\n", "[+] Successufully cleared SACL");

return 0;

}

PACL pOldSACL = NULL;

PSECURITY_DESCRIPTOR pPipeSD = NULL;

// Just need an already existing SACL to be able to edit it

if (GetSecurityInfo(hPipe, SE_KERNEL_OBJECT, SACL_SECURITY_INFORMATION, NULL, NULL, NULL, &pOldSACL, &pPipeSD) != ERROR_SUCCESS)

{

printf("%s\n%d\n", "GetSecurityInfo", GetLastError());

return 1;

}

// Init TRUSTEE, which is basically SACL stucture

TRUSTEE trusteeSACL[1];

trusteeSACL[0].TrusteeForm = TRUSTEE_IS_NAME;

trusteeSACL[0].TrusteeType = TRUSTEE_IS_GROUP;

trusteeSACL[0].ptstrName = groupName;

trusteeSACL[0].MultipleTrusteeOperation = NO_MULTIPLE_TRUSTEE;

trusteeSACL[0].pMultipleTrustee = NULL;

EXPLICIT_ACCESS explicit_access_listSACL[1];

ZeroMemory(&explicit_access_listSACL[0], sizeof(EXPLICIT_ACCESS));

// Here I buit SACL

explicit_access_listSACL[0].grfAccessMode = SET_AUDIT_SUCCESS;

// I wasn't able to made two right at the same time.

//explicit_access_listSACL[0].grfAccessMode = SET_AUDIT_FAILURE;

// If your change GENERIC_ALL, to something else, like ACCESS_SECURITY, then SACL will audit only handles with ACCESS_SECURITY rights.

explicit_access_listSACL[0].grfAccessPermissions = GENERIC_ALL;

explicit_access_listSACL[0].grfInheritance = NO_INHERITANCE;

explicit_access_listSACL[0].Trustee = trusteeSACL[0];

PACL pNewSACL = NULL;

PACL pNewSACLFal = NULL;

// This is not ideal, but I dont know how to unite SET_AUDIT_SUCCESS and SET_AUDIT_FAILURE and I dont want to waste much time on it.

if (SetEntriesInAcl(1, explicit_access_listSACL, pOldSACL, &pNewSACL) != ERROR_SUCCESS)

{

printf("%s\n%d\n", "SetEntriesInAcl", GetLastError());

return 1;

}

explicit_access_listSACL[0].grfAccessMode = SET_AUDIT_FAILURE;

if (SetEntriesInAcl(1, explicit_access_listSACL, pNewSACL, &pNewSACLFal) != ERROR_SUCCESS)

{

printf("%s\n%d\n", "SetEntriesInAcl", GetLastError());

return 1;

}

if (SetSecurityInfo(hPipe, SE_KERNEL_OBJECT, SACL_SECURITY_INFORMATION, NULL, NULL, NULL, pNewSACLFal) != ERROR_SUCCESS)

{

printf("%s\n%d\n", "SetSecurityInfo", GetLastError());

return 1;

}

printf("%s\n", "[+] Successufully set SACL");

LocalFree(pNewSACL);

LocalFree(pNewSACLFal);

LocalFree(pOldSACL);

CloseHandle(hPipe);

}Также для работы SACL должны быть включены следующие политики аудита:

Доступ к объектам | Object Access

--> Объект-задание (Успех и сбой) | Kernel Object Success and Failure (Success and Failure)

--> Работа с дескриптором (Успех и сбой) | Handle Manipulation Success and Failure () (Success and Failure)

// Дополнительная информация, не работает без Объект-заданиеRPC Filtering

Интересной альтернативой событиям, поставляемым через ETW провайдеры, может быть RPC Filtering. Решение устанавливается на конечное устройство и основано на возможностях межсетевого экрана самой ОС. Из плюсов — мы имеем возможность просмотра события в привычном нам Event Viewer. Но как и в случае с SACL, требуется предварительное выполнение настройки. Можно воспользоваться двумя способами:

-

Утилитой netsh.exe;

-

Использовать WinAPI.

В качестве примера возьмем RPC‑интерфейс, который связан с ранее упомянутой атакой PetitPotam — EFS.

rpc filter

add rule layer=um actiontype=permit audit=enable

add condition field=if_uuid matchtype=equal data=c681d488-d850-11d0-8c52-00c04fd90f7e

add filter

Установить правило можно с помощью утилиты netsh:

netsh -f rpcauditrule.txtПри выполнении обращения был получен следующий лог:

<REDACTED>

LogName=Security

EventCode=5712

EventType=0

ComputerName=<REDACTED>

SourceName=Microsoft Windows security auditing.

Type=Information

RecordNumber=39145598

Keywords=Audit Success

TaskCategory=RPC Events

OpCode=Info

Message=A Remote Procedure Call (RPC) was attempted.

Subject:

SID: S-1-5-7

Name: ANONYMOUS LOGON

Account Domain: NT AUTHORITY

LogonId: 0x95FDD924

Process Information:

PID: 716

Name: lsass.exe

Network Information:

Remote IP Address: 0.0.0.0

Remote Port: 0

RPC Attributes:

Interface UUID: {c681d488-d850-11d0-8c52-00c04fd90f7e}

Protocol Sequence: ncacn_np

Authentication Service: 0

Authentication Level: 0Этот метод является прекрасной альтернативой ETW. Он не только генерирует удобный лог, но и имеет бОльшую информативность (например, наличие поля Subject). Также у такого метода нет каких‑либо технических ограничений по сбору событий, это все тот же EventLog.

RPC Firewall

Коллеги из Zero Networks предлагают идти дальше. С помощью решения RPC‑firewall, которое устанавливается на конечное устройство, они рассматривают возможность не только мониторинга, но блокировки конкретных RPC методов, чего нельзя сделать через стандартный Windows Firewall. Дополнительным бонусом предлагается заметно улучшенный журнал событий, так как в нем будет присутствовать информация о номере процедуры (ProcNum/ OpNum).

Закончив с уровнем операционной системы, перейдем к сетевому.

Сетевой уровень

Сетевой трафик весьма информативен. При его мониторинге мы можем увидеть не только подключение к IPC$ ресурсу, но и сразу номер процедуры (ProcNum/ OpNum). Это очень полезно, так как у нас появляется вся нужная информация о клиенте, а именно:

-

Кто именно клиент (так как мы видим Bind подключение);

-

Куда клиент подключается;

-

Какие именно функции выполняет клиент;

-

Как на них реагирует сервер (Ошибка или Успех).

Интереснее всего это получать информацию о выполняемых клиентом функциях, поскольку такие данные могут предоставить только ETW, RPC Firewall и трафик.

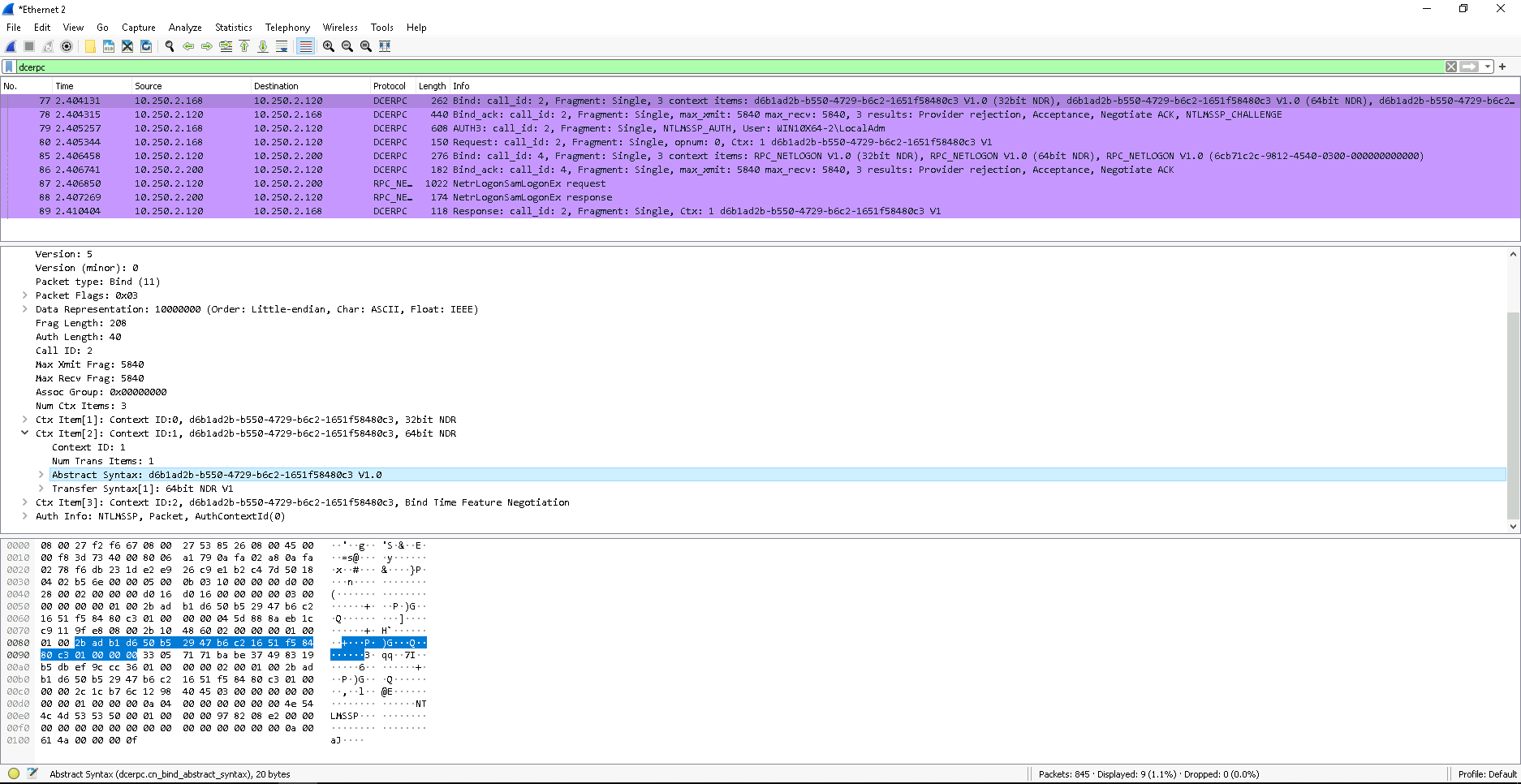

На рисунке 14 приведен пример NPs ориентированного подключения, где виден номер операции, в нашем случае это 64, в атрибуте SAMR → Operation.

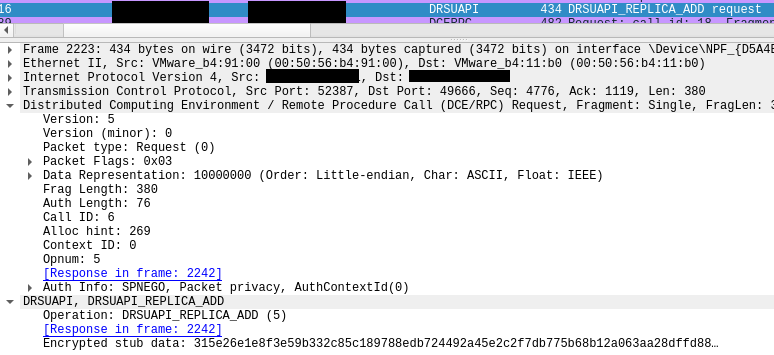

Таким же образом можно просматривать и поведение TCP‑ориентированных подключений. В примере была запущена репликация домен‑контроллера, где мы можем увидеть RPC запрос вместе с номером процедуры (в примере на рисунке 15 он равен 5) и интерфейсом подключения (в примере это DRSUAPI).

Шифрование

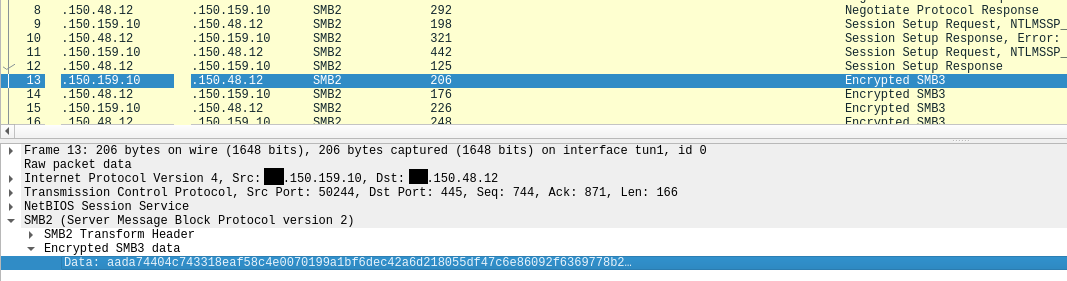

Тема шифрования RPC‑трафика до этого в статье не затрагивалась, тем не менее оно есть. Шифрование может добавить проблем при мониторинге трафика в сети, так как расшифровывать его сложно, да и никто не любит это делать.

Трафик можно разделить на 2 вида:

-

на инкапсулированный в TCP/ UDP/ HTTP и не предполагающий никакого шифрования кроме того, что реализовано в самом RPC протоколе;

-

на использование NPs через SMB протокол.

Посмотрим как это выглядит в Wireshark (рисунок 16). В RPC трафике видно NPs, к которому обращается клиент, а также вызываемую функцию, поскольку эти данные не зашифрованы, а зашифрованы только аргументы к функции. Напомним, что любая функция RPC имеет свой OpNum, статически закреплённый за каждой из них. Так функции можно точно идентифицировать.

С SMB так не получится. Если используется SMB версии 3, то весь трафик целиком будет зашифрован и ничего нельзя будет увидеть. SMB3 поддерживается всеми современными версиями Windows и злоумышленник без проблем может использовать его, чтобы скрыть свои действия.

Поэтому если есть необходимость мониторить RPC взаимодействие, то можно это сделать через протокол SMB, либо если нужно выбрать один источник для мониторинга всего и сразу, то трафик лучше не использовать.

Заключение

В этой статье мы разобрали механизмы работы RPC, протоколы его интерфейсов и основные способы мониторинга удаленного вызова функций. Определенно, при сравнении всех трёх подходов логирования для мониторинга фаворитом будет являться ETW. Но в частных случаях, когда, например, точно известно об ограниченных возможностях злоумышленника и его неспособности использовать TCP‑ориентированное подключение, существует вариант применения политик аудита. В случае, если можно провести мониторинг трафика, такой способ имеет шанс стать альтернативой ETW и другим средствам логирования. Но здесь важно помнить о возможности его шифрования, если атакующий использует SMB.

|

Метод логирования |

Информативность |

Простота настройки |

|---|---|---|

|

ETW |

+ |

+ |

|

Журналы безопасности |

+/- |

+ |

|

SACL |

+ |

— |

|

Сетевой трафик |

+ |

— |

Схема источников логов

Ниже представлена схема, показывающая возможности атакующего при подключении к сервису RPC и каким образом можно cобирать события по каждому из вариантов подключения.

Если у вас остались вопросы, пишите в комментариях. Надеемся, статья оказалась вам полезной!

Авторы:

— Черных Кирилл (@Ruucker), аналитик-исследователь киберугроз;

— Мавлютова Валерия (@Iceflipper), младший аналитик-исследователь киберугроз.

Penetration Testing as a service (PTaaS)

Tests security measures and simulates attacks to identify weaknesses.

MS-RPC (удаленный вызов процедуры Microsoft) протокол — это проприетарный протокол, разработанный корпорацией Майкрософт для обмена данными между программными приложениями, работающими на разных устройствах в сетевой среде.

MS-RPC на основе DCE/RPC. Часто работает с SMB, поэтому эти данные могут быть полезны при атаке на SMB.

Общие порты MS-RPC

Port 135: Это хорошо известный порт, используемый службой сопоставления конечных точек MS-RPC для обеспечения сопоставления с динамическими портами, используемыми другими службами.

Динамические порты: службы MS-RPC используют динамические порты, что означает, что порты выделяются службой endpoint mapper по мере необходимости. Диапазон динамических портов, используемых MS-RPC, составляет 49152 Для 65535.

Некоторые из распространенных служб MS-RPC и связанных с ними портов являются:

Служба удаленного вызова процедур (RPC): Порт 135

Распределенная файловая система (DFS): Порт 445

Служба диспетчера очереди печати: Порт 135, 139, 445

Активный каталог: Порт 389, 636 (для SSL)

Инструментарий управления Windows (WMI): Порт 135, динамические порты

Протокол удаленного рабочего стола (RDP): Порт 3389

Стандартные команды от неавторизованных

rpcclient 46.163.74.38 rpcclient 46.163.74.38

Разведывательная или нестандартная команда

rpcinfo -p 46.163.74.38 (Определить, какие RPC запущены)

nmap -sV <target> (rpcinfo called)

Нулевое сеансовое соединение

rpcclient -U “” 46.163.74.38 <enter without input>

Связь с перечислением

https://github.com/SecureAuthCorp/impacket/blob/master/examples/rpcdump.py (не проверено)

Enumerating RPC interfaces by using rpcdump – rpcdump 46.163.74.38 -v

nmap <target> –script=msrpc-enum

enum4linux.pl -а 46.163.74.38

или

rpcclient -U “” 46.163.74.38 –command=<command>

Commands: enumprivs, srvinfo, netshareenumall, netsharegetinfo <netname from netshareenumall>, netfileenum, netsessenum, netdiskenum, netconnenum, enumdomusers, enumdomgroups, enumdomains, enumtrust

https://github.com/p33kab00/dcerpc-pipe-scan

Инструменты для использования протокола MS-RPC

Ручные Инструменты:

-

RPCPing: Инструмент Microsoft, используемый для тестирования подключения к RPC и выявления проблем. Он отправляет RPC-пакет на целевой сервер и ожидает ответа.

-

PortQry: Еще один инструмент Microsoft, который можно использовать для проверки того, прослушивают ли определенные службы RPC определенный порт в целевой системе.

-

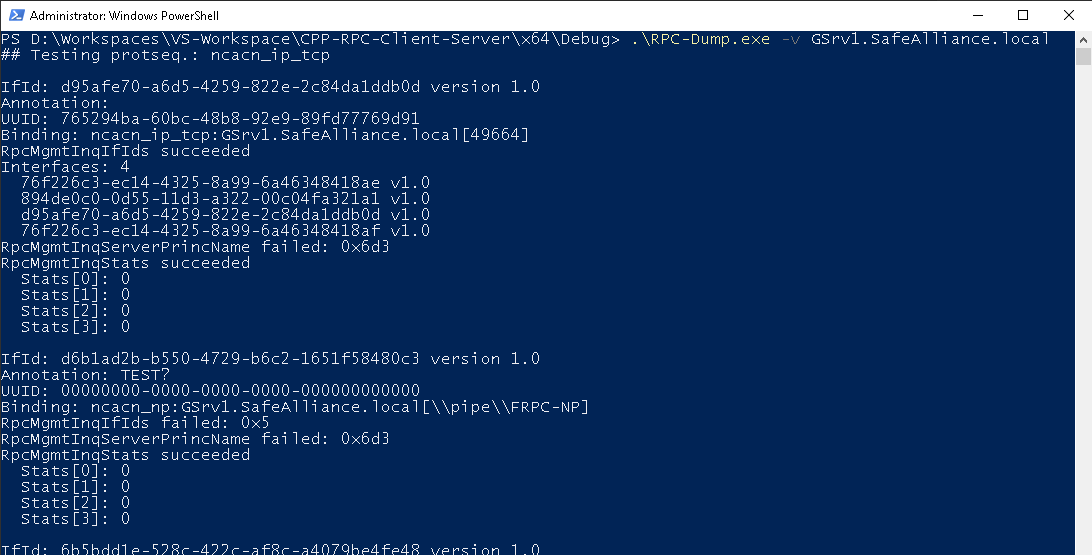

RPCDump: Инструмент, используемый для сбора и анализа сетевого трафика между RPC-клиентом и сервером. Это может помочь выявить проблемы с вызовами RPC и может быть использовано для устранения неполадок.

-

RPCCrack: Инструмент, используемый для взлома паролей для служб RPC. Он может быть использован для тестирования безопасности служб RPC путем попытки взлома паролей.

-

RPCEcho: Инструмент, который отправляет базовое RPC-сообщение на целевой сервер и проверяет наличие ответа. Его можно использовать для тестирования подключения к RPC и выявления проблем.

-

WinRPC Checker: Инструмент, используемый для проверки конфигурации служб RPC в целевой системе. Его можно использовать для проверки правильности настройки и защиты служб RPC.

-

Impacket: Библиотека Python, используемая для создания и отправки пакетов по сети. Его можно использовать для создания пользовательских пакетов RPC в целях тестирования.

-

Metasploit Framework: Популярный инструмент тестирования на проникновение, который включает в себя модули для тестирования RPC-сервисов. Его можно использовать для проверки на наличие уязвимостей и использования их в случае обнаружения.

Автоматизированные инструменты:

-

Nmap: Популярный инструмент сетевого сканирования, который включает в себя возможности сканирования RPC. Он может быть использован для идентификации служб RPC и связанных с ними портов в целевой системе.

-

OpenVAS: Инструмент сканирования уязвимостей с открытым исходным кодом, который включает модули для тестирования служб RPC. Он может быть использован для выявления уязвимостей в службах RPC и предоставления рекомендаций по устранению.

-

Qualys: Облачный инструмент сканирования уязвимостей, включающий модули для тестирования служб RPC. Он может быть использован для выявления уязвимостей в службах RPC и предоставления рекомендаций по устранению.

-

Nessus: Еще один популярный инструмент сканирования уязвимостей, который включает в себя модули для тестирования служб RPC. Он может быть использован для выявления уязвимостей в службах RPC и предоставления рекомендаций по устранению.

-

Retina CS: Инструмент сканирования уязвимостей, который включает модули для тестирования служб RPC. Он может быть использован для выявления уязвимостей в службах RPC и предоставления рекомендаций по устранению.

-

Rapid7: Инструмент управления уязвимостями, который включает модули для тестирования служб RPC. Он может быть использован для выявления уязвимостей в службах RPC и предоставления рекомендаций по устранению.

-

Burp Suite: Популярный инструмент тестирования веб-приложений, включающий модули для тестирования служб RPC. Его можно использовать для тестирования безопасности служб RPC, запущенных в веб-приложениях.

-

ZAP: Еще один популярный инструмент тестирования веб-приложений, который включает в себя модули для тестирования служб RPC. Его можно использовать для выявления уязвимостей в службах RPC, работающих в веб-приложениях.

-

Acunetix: Инструмент тестирования веб-приложений, включающий модули для тестирования служб RPC. Его можно использовать для выявления уязвимостей в службах RPC, работающих в веб-приложениях.

-

AppSpider: Инструмент тестирования веб-приложений, включающий модули для тестирования служб RPC. Его можно использовать для выявления уязвимостей в службах RPC, работающих в веб-приложениях.

-

Nexpose: Инструмент сканирования уязвимостей, который включает модули для тестирования служб RPC. Он может быть использован для выявления уязвимостей в службах RPC и предоставления рекомендаций по устранению.

-

Core Impact: Коммерческий инструмент тестирования на проникновение, который включает модули для тестирования служб RPC. Его можно использовать для проверки на наличие уязвимостей и использования их в случае обнаружения.

Все известные CVE для MS-RPC

• CVE-2017-10608: На любом устройстве серии Juniper Networks SRX с одним или несколькими включенными ALGS может произойти сбой flowd при обработке трафика с помощью ALGS Sun / MS-RPC. Эта уязвимость в компоненте служб Sun / MS-RPC ALG ОС Junos позволяет злоумышленнику вызывать повторный отказ в обслуживании цели. Повторяющийся трафик в кластере может привести к повторным сбоям триггера или полному отказу демона flowd, останавливающему трафик на всех узлах. Эта проблема затрагивает только трафик IPv6. Трафик IPv4 не затронут. Эта проблема не связана с трафиком на хост. Эта проблема не имеет никакого отношения к самим службам HA, только к службе ALG. Эта проблема не затрагивает никакие другие продукты или платформы Juniper Networks. Затронутыми версиями являются Juniper Networks Junos OS 12.1X46 до 12.1X46-D55 на SRX; 12.1X47 до 12.1X47-D45 на SRX; 12.3X48 до 12.3X48-D32, 12.3X48-D35 на SRX; 15.1X49 до 15.1X49-D60 на SRX.

• CVE-2007-4044: ** ОТКЛОНИТЬ ** Функциональность MS-RPC в smbd в Samba 3 на SUSE Linux до 20070720 не включает «один символ в обработке экранирования оболочки”. ПРИМЕЧАНИЕ: эта проблема первоначально характеризовалась как проблема с метасимволами оболочки из-за неполного исправления для CVE-2007-2447, которое было интерпретировано CVE как относящееся к безопасности. Однако SUSE и Red Hat оспорили проблему, заявив, что единственное влияние заключается в том, что скрипты не будут выполняться, если в их названии есть буква “c”, но даже этого ограничения может не существовать. Это не имеет последствий для безопасности, поэтому не должно быть включено в CVE.

• CVE-2007-2447: Функциональность MS-RPC в smbd в Samba с 3.0.0 по 3.0.25rc3 позволяет удаленным злоумышленникам выполнять произвольные команды с помощью метасимволов оболочки, включающих (1) функцию SamrChangePassword, когда включена опция smb.conf “сценарий сопоставления имени пользователя”, и позволяет удаленным аутентифицированным пользователям выполнять команды с помощью метасимволов оболочки, включающих другие функции MS-RPC в (2) удаленном принтере и (3) управлении общим файлом.

• CVE-2007-2446: Множественные переполнения буфера на основе кучи при анализе NDR в smbd в Samba с 3.0.0 по 3.0.25rc3 позволяют удаленным злоумышленникам выполнять произвольный код с помощью обработанных запросов MS-RPC, включающих (1) DFSEnum (netdfs_io_dfs_EnumInfo_d), (2) RFNPCNEX (smb_io_notify_option_type_data), (3) LsarAddPrivilegesToAccount (lsa_io_privilege_set), (4) NetSetFileSecurity (sec_io_acl), или (5) LsarLookupSids/LsarLookupSids2 (lsa_io_trans_names).

Полезная информация

– MS-RPC (удаленный вызов процедур Microsoft) — это протокол, используемый операционными системами Windows, позволяющий программам отправлять запросы и получать ответы от других программ по сети.

– MS-RPC использует архитектуру клиент-сервер, где клиентская программа отправляет запрос серверной программе, которая обрабатывает запрос и отправляет ответ обратно клиенту.

– MS-RPC поддерживает широкий спектр служб, включая общий доступ к файлам и принтерам, удаленный доступ к реестру и службы удаленного вызова процедур для различных служб Windows.

– MS-RPC по умолчанию использует порт 135, но также может использовать динамические порты выше 1024.

– MS-RPC использует уникальный идентификатор (UUID) для идентификации каждой службы, а преобразователь сетевых адресов (NAT) может сопоставить UUID с определенным номером порта.

– MS-RPC может быть уязвим для целого ряда атак, включая атаки типа «отказ в обслуживании» (DoS), переполнение буфера и атаки типа «человек посередине» (MITM).

– Некоторые распространенные инструменты для тестирования и использования уязвимостей MS-RPC включают Metasploit, rpcclient и Responder.

– Для устранения уязвимостей MS-RPC рекомендуется использовать брандмауэры для блокирования трафика на порту 135 и обеспечения того, чтобы все системы Windows обновлялись последними исправлениями безопасности.

– Системы Windows также могут быть настроены на использование ограниченного набора служб, которым разрешено использовать MS-RPC, что может помочь уменьшить поверхность атаки.

– Кроме того, администраторы могут использовать средства мониторинга сетевой безопасности для обнаружения и блокирования трафика MS-RPC, который не авторизован или указывает на атаку.

- Веб-уязвимости

- Процесс тестирования

- Отчеты

- Соответствие требованиям

- Протоколы

Книги для изучения удаленного вызова процедур Microsoft (MS-RPC)

“Руководство по программированию Microsoft RPC” автор: Марко Хаверкорн: Эта книга представляет собой исчерпывающее руководство по программированию на MS-RPC, включая то, как использовать API, как создавать распределенные приложения и как устранять распространенные проблемы.

“Ссылка на собственный API для Windows NT / 2000” автор Гэри Неббетт: Эта книга содержит подробную информацию о собственном API, который включает реализацию MS-RPC.

“Внутренняя отладка Windows” автор Тарик Соулами: В этой книге рассматриваются передовые методы отладки для Windows, включая отладку MS-RPC.

“Книга драйверов устройств Windows 2000: руководство для программистов” Арт Бейкер и Джерри Лозано: В этой книге представлен обзор драйверов устройств Windows 2000, в том числе о том, как использовать MS-RPC для обмена данными между драйверами.

“Внутренние компоненты Windows, часть 2 (6-е издание)” автор: Марк Руссинович, Дэвид Соломон и Алекс Ионеску: В этой книге рассказывается о внутренней работе Windows, включая MS-RPC.

“Сетевое программирование Windows” Ричард Блюм: В этой книге подробно рассматривается сетевое программирование Windows, включая MS-RPC.

“Внутренние компоненты файловой системы Windows NT” автор Раджив Нагар: В этой книге рассказывается о файловой системе Windows NT, в том числе о том, как MS-RPC используется для обмена данными между компонентами файловой системы.

“Системное программирование Windows, Четвертое издание” Джонсон М. Харт: Эта книга посвящена системному программированию Windows, включая MS-RPC.

“Windows Forensic Analysis Toolkit, четвертое издание: Расширенные методы анализа для Windows 8” автор Харлан Карви: В этой книге рассматриваются передовые методы криминалистического анализа Windows, в том числе как использовать MS-RPC для удаленных вызовов процедур во время расследований.

“Программирование безопасности Windows” Кит Браун: В этой книге рассказывается о программировании безопасности Windows, в том числе о том, как MS-RPC можно использовать для аутентификации и контроля доступа.

Список полезной нагрузки для удаленного вызова процедуры Microsoft (MS-RPC)

-

Служба удаленного вызова процедур (RPC): Полезная нагрузка для службы RPC может включать в себя такие параметры, как идентификатор интерфейса, идентификатор операции и данные, подлежащие передаче.

-

Распределенная файловая система (DFS): Полезная нагрузка для DFS включает информацию о файле или каталоге, к которому осуществляется доступ, такую как путь, дескриптор файла и права доступа.

-

Служба диспетчера очереди печати: Полезная нагрузка для службы диспетчера очереди печати включает данные о задании печати, такие как идентификатор задания, имя принтера и данные печати.

-

Активный Каталог: Полезная нагрузка для Active Directory может включать запросы на создание, изменение или удаление объектов, а также запросы на получение информации об объектах и их атрибутах.

-

Инструментарий управления Windows (WMI): Полезная нагрузка для WMI включает запросы и команды для извлечения или изменения системной информации, такой как конфигурация оборудования, производительность системы и журналы событий.

-

Протокол удаленного рабочего стола (RDP): Полезная нагрузка для RDP включает в себя такие данные, как ввод с клавиатуры и мыши, аудио- и видеопотоки и содержимое буфера обмена, которые передаются между клиентом и сервером во время сеансов удаленного рабочего стола.

Смягчение последствий

-

Постоянно обновляйте системы: убедитесь, что все системы, на которых работает MS-RPC, обновлены последними исправлениями безопасности от поставщика.

-

Внедрять правила брандмауэра: Используйте брандмауэры для блокирования трафика на порты, связанные с MS-RPC, и из них, которые не требуются для бизнес-целей.

-

Внедрите контроль доступа: Ограничьте доступ к службам MS-RPC только тем пользователям, которым это необходимо для выполнения их рабочих обязанностей.

-

Отключить ненужные службы: отключите все ненужные службы MS-RPC, запущенные в системах, чтобы уменьшить поверхность атаки.

-

Используйте сегментацию сети: сегментируйте сети, чтобы ограничить доступ служб MS-RPC только к тем системам, которые в них нуждаются.

-

Внедрите надежную аутентификацию: используйте надежные методы аутентификации, такие как многофакторная аутентификация, для предотвращения несанкционированного доступа к службам MS-RPC.

-

Мониторинг системных журналов: Регулярно просматривайте системные журналы на предмет любых признаков подозрительной активности, таких как неудачные попытки входа в систему или попытки несанкционированного доступа.

-

Используйте системы обнаружения вторжений: Используйте системы обнаружения вторжений для обнаружения любых попыток использования уязвимостей MS-RPC и оповещения о них.

-

Выполняйте регулярные оценки безопасности: Регулярно выполняйте оценки безопасности для выявления и устранения любых уязвимостей во внедрении MS-RPC.

Заключение

МС-RPC это широко используемый протокол для удаленных вызовов процедур в средах Microsoft Windows. Хотя он обеспечивает удобный способ взаимодействия программных приложений по сети, он также имеет историю уязвимостей, которыми могут воспользоваться злоумышленники. Чтобы уменьшить эти уязвимости, организации могут предпринять такие шаги, как постоянное обновление систем, внедрение средств контроля доступа, использование сегментации сети и выполнение регулярных оценок безопасности. Внедряя эти меры, организации могут снизить риск атак, нацеленных на MS-RPC, и помочь обеспечить безопасность своих систем и данных.

October 8, 2019 (Revised March 27, 2022)

In this article…

- What is the RPC Windows Service?

- Should I stop the RPC service?

- Why are all the options for the RPC service grayed out?

- Questions? Problems?

What is the RPC Windows Service?

The Remote Procedure Call (RPC) service supports communication between Windows applications.

Specifically, the service implements the RPC protocol — a low-level form of inter-process communication where a client process can make requests of a server process. Microsoft’s foundational COM and DCOM technologies are built on top of RPC.

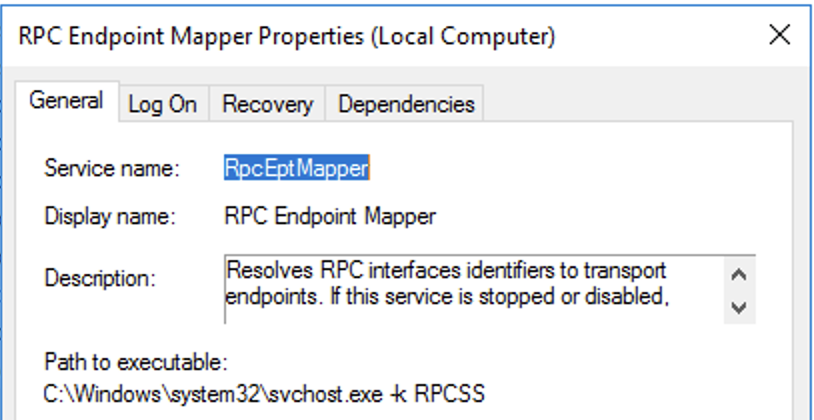

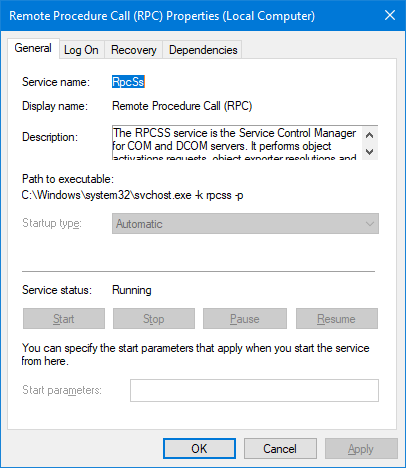

The service’s name is RpcSs and it runs inside the shared services host process, svchost.exe:

Should I stop the RPC service?

The answer is no — you should definitely not stop the service. It is far too important.

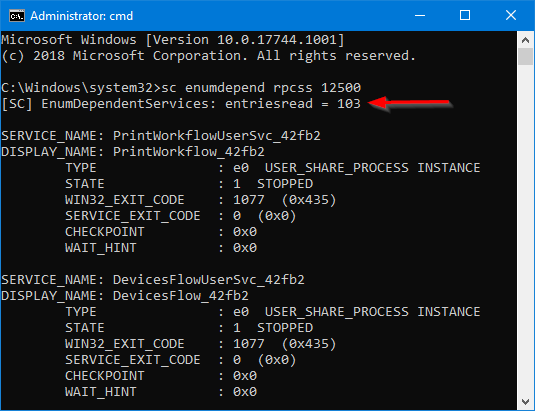

Indeed, if you examine the list of services that depend on the RPC service for smooth operation — by running the SC ENUMDEPEND command — you will notice that there are a whopping 103 services that need RpcSs on Windows Server 2019!

If the RPC service stops, those 103 would have to stop as well — surely crippling your computer.

In their guidance on disabling system services on Windows Server 2016, Microsoft “strongly recommends that you have the RPCSS service running”. However that is a huge understatement. The service is absolutely vital for Windows to run.

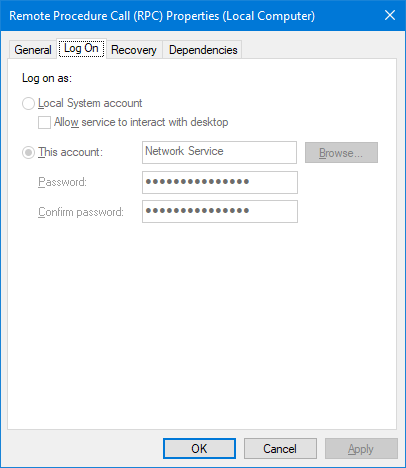

Why are all the options for the RPC service grayed out?

If you examine the service’s screenshot, you will notice that the Stop and Pause buttons are disabled — indicating that the service cannot be interrupted.

Furthermore, the account running the service cannot be changed on the Log On tab:

You can adjust the recovery settings but not much else.

By limiting changes, Microsoft is clearly shouting: Do not update the RPC service!

Questions? Problems?

If you would like to know more about the Windows RPC service, or you have a specific problem, please feel free to get in touch. We will do our best to help you!

You may also like…

What Is Remote Procedure Call on Windows: Complete Guide

In the ever-evolving landscape of computing, where software applications need to communicate effortlessly across networks, Remote Procedure Call (RPC) emerges as a critical technology. This guide will delve into what RPC is, particularly within the Windows operating system, outlining its architecture, mechanisms, uses, and best practices. Whether you are a developer, a system administrator, or an IT enthusiast, understanding RPC on Windows is pivotal for creating robust and efficient applications.

Understanding Remote Procedure Call (RPC)

Remote Procedure Call is a protocol that allows a program to execute a procedure on a different address space or machine as if it were being executed locally. While the underlying architecture of RPC can involve complex interprocess communication (IPC) systems, the essence lies in abstraction. RPC abstracts the intricacies of networking, enabling developers to call functions or procedures with parameters seamlessly, similar to local function calls.

RPC plays a pivotal role in a variety of distributed systems, enabling services to collaborate efficiently. When a program makes an RPC call, it sends a request to a remote server, which processes the call and returns the result back to the original requester. This model significantly simplifies distributed computing as it hides the complexity of the underlying communication.

A Brief History of RPC

The idea of RPC dates back to the 1980s when it was first introduced in the context of network programming. Initially, RPC was developed for systems utilizing the UNIX operating system but soon made its way to other platforms, including Windows. Microsoft incorporated RPC into its Windows architecture through Distributed Component Object Model (DCOM) and various other services, allowing for smoother integration of distributed applications.

The Architecture of RPC

At its core, the RPC architecture consists of several key components, which can be broken down into the following layers:

-

Client-Side Stub: This acts as a proxy for the client who wants to call a remote procedure. The client-side stub marshals the parameters into a message that can be transmitted over a network.

-

Server-Side Stub: This component is responsible for un-marshaling the message received from the client, extracting the parameters, and calling the appropriate service on the server.

-

Transport Layer: The transport layer handles the actual transmission of messages over the network using various protocols like TCP/IP, UDP, or named pipes.

-

Service Procedure: This is the actual function that will execute on the server side. After the parameters are received and un-marshaled by the server-side stub, it passes them to the service procedure.

-

Registry and Interface Definitions: In Windows, RPC also uses the Windows Registry to store interface details. These definitions describe the data structures and methods available for remote calls.

How Remote Procedure Call Works in Windows

When the client application initiates an RPC request, the process unfolds as follows:

-

Procedure Call: The client application invokes a function call that is intended to execute on a remote server.

-

Client Stub: The client-side stub marshals the parameters needed for the procedure into a network-compatible format and communicates with the transport layer to send the data to the server.

-

Transport Layer: Using the specified transport protocol, like TCP/IP, the marshaled data is sent over the network to the server’s address.

-

Server Stub: At the server end, the server-side stub receives the marshaled message. It unmarshals the data to extract the original parameters and calls the actual service procedure with those parameters.

-

Service Execution: The service processes the request and generates a response, which the server stub marshals back into a message format.

-

Response Back to Client: The message is sent back to the client through the transport layer, where the client-side stub unmarshals it, allowing the client to complete the function call with the returned result.

This seamless process, from initiating a call to receiving a response, highlights why RPC is favored in distributed systems, especially on Windows environments.

Common Uses of RPC on Windows

RPC is implemented in numerous applications and services within the Windows ecosystem. Some of the primary uses include:

-

Distributed Applications: Applications designed to run on multiple machines leverage RPC for communicating between client and server components.

-

Microsoft DCOM: The Distributed Component Object Model is one of the prominent applications of RPC in Windows, allowing for dynamic communication between Windows-based applications.

-

File and Print Sharing: RPC facilitates communication in services like file and print sharing where resources need to be accessed over a network.

-

Active Directory: RPC is crucial in maintaining communication between domain controllers and managing user accounts, authentication, and more in Active Directory.

-

Remote Management Tools: Admin tools for remote server management often use RPC to execute commands and retrieve data from remote systems.

Security Implications of RPC

While RPC enhances interoperability, it also introduces various security concerns. Key security considerations when implementing RPC on Windows include:

-

Authentication: Ensuring that only authorized users can initiate RPC calls is critical. Windows offers various authentication methods, including Kerberos and NTLM.

-

Encryption: RPC data can be interceptable, making it essential to encrypt communications to ensure confidentiality.

-

Access Control: Windows implements access control lists (ACLs) to define who can access the RPC services, limiting exposure to malicious actors.

-

Firewall Configuration: Properly configuring Windows Firewall to control inbound and outbound RPC traffic is crucial for securing the systems from unauthorized access.

-

Extinguishing Vulnerabilities: Developers should be aware of and rectify any potential vulnerabilities in their RPC interfaces, such as buffer overflow risks, ensuring robust error handling and parameter validation.

Best Practices for Implementing RPC on Windows

To optimize RPC usage and maximize security, consider the following best practices:

-

Use Windows RPC Libraries: Leverage the built-in RPC libraries provided by Windows, which are optimized for performance and security, rather than creating a custom implementation.

-

Maintain High-Level Abstraction: Keep your RPC architecture as high-level as possible to minimize complexity. Use suitable abstractions such as protocols or frameworks whenever feasible.

-

Regulate Network Access: Limit RPC traffic to necessary ports and IP addresses to reduce the attack surface, ensuring only trusted sources can access RPC services.

-

Monitor Logs and Traffic: Implement logging to track RPC calls. This helps identify unauthorized access attempts or unusual patterns that might indicate vulnerabilities or security breaches.

-

Regular Update and Patch Management: Regular updates of your operating system and applications can mitigate vulnerabilities associated with RPC. Keeping software up-to-date is crucial as many exploits rely on outdated systems.

-

Leverage Firewall Rules: Implement stringent firewall rules to manage communication, regulating which ports and IP addresses are permissible for RPC traffic.

-

Ensure Robust Error Handling: Implement powerful error handling and logging for RPC calls to mitigate crash risks or unexpected behavior in production environments.

-

Validate Input Parameters: Always validate and sanitize input parameters sent via RPC calls to prevent injection attacks such as buffer overflows or SQL injections.

-

Consider Using .NET Remoting: For applications developed in .NET, consider using the .NET Remoting framework, which simplifies many aspects of RPC while providing higher security.

-

Conduct Security Audits: Regularly perform security assessments and audits on your RPC interfaces to identify and remedy potential vulnerabilities.

Conclusion

Remote Procedure Call (RPC) is a powerful communication paradigm that plays a significant role in modern distributed systems. Particularly on the Windows platform, RPC provides developers and system administrators with the tools to create robust applications that can communicate effectively across different environments.

Understanding the architecture, working mechanisms, applications, and security implications of RPC is essential for anyone venturing into networked or distributed application development on Windows. By adhering to best practices and staying informed with proper protocols and security measures, organizations can harness the full potential of RPC while safeguarding their systems against potential vulnerabilities.

With its rich history and robust functionality, RPC remains a cornerstone of distributed computing, and its relevance in today’s technological landscape is more pronounced than ever. As systems continue to evolve, RPC will likely adapt and integrate with emerging technologies, ensuring its place as a fundamental component for efficient communication in distributed applications on Windows and beyond.

Contents:

- The Series

- Introduction

- History

- RPC Messaging

- RPC Protocol Sequence

- RPC Interfaces

- RPC Binding

- Anonymous & Authenticated Bindings

- Registration Flags

- Security Callbacks

- Authenticated Bindings

- Well-known vs Dynamic Endpoints

- RPC Communication Flow

- Sample Implementation

- Access Matrix

- Attack Surface

- Finding Interesting Targets

- RPC Servers

- RPC Clients

- Client Impersonation

- Server Non-Impersonation

- MITM Authenticated NTLM Connections

- MITM Authenticated GSS_NEGOTIATE Connections

- Finding Interesting Targets

- References

The Series

This is part 2 of my series: Offensive Windows IPC Internals.

If you missed part one and want to take a look, you’ll find it here: Offensive Windows IPC Internals 1: Named Pipes.

Part 2 was originally planned to be about LPC & ALPC, but as it turns out it’s quite time consuming to dig out all the undocumented bits and tricks about these technologies. Therefore i made the discussion to publish my knowledge about RPC first before turning my head towards ALPC once again.

The reason why i originally planed to publish LPC & ALPC before RPC is because RPC uses ALPC under the hood when used locally and even more: RPC is the intended solution for fast local inter process communication as RPC can be instructed to process local communication via a special ALPC protocol sequence (but you’ll find that out while reading on).

Anyhow, the lesson here is (i guess) that sometimes its better to pause on a thing and get your head cleared up and make progress with something else before you get lost in something that is just not ready to reveal its mysteries to you.

Get a coffee and a comfy chair and buckle up for RPC…

Introduction

Remote Procedure Calls (RPC) is a technology to enable data communication between a client and a server across process and machine boundaries (network communication). Therefore RPC is an Inter Process Communication (IPC) technology. Other technologies in this category are for example LPC, ALPC or Named Pipes.

As the name and this category implies RPC is used to make calls to remote servers to exchange/deliver data or to trigger a remote routine. The term “remote” in this case does not describe a requirement for the communication. An RPC server does not has to be on a remote machine, and in theory does not even has to be in a different process (although this would make sense).

In theory you could implement a RPC server & client in DLLs, load them into the same process and exchange messages, but you wouldn’t gain much as the messages would still be routed through other components outside of your process (such as the kernel, but more on this later) and you would try to make use of an “Inter” Process Communication technology for “Intra” Process Communication.

Moreover a RPC server does not need to be on a remote machine, but could as well be called from a local client.

Within this blog post you can join me in discovering the insides of RPC, how it works & operates and how to implement and attack RPC clients and servers.

This post is is made from an offensive view point and tries to cover the most relevant aspects the attack surface of RPC from an attackers perspective. A more defensive geared view on RPC can for example be found at https://ipc-research.readthedocs.io/en/latest/subpages/RPC.html by Jonathan Johnson

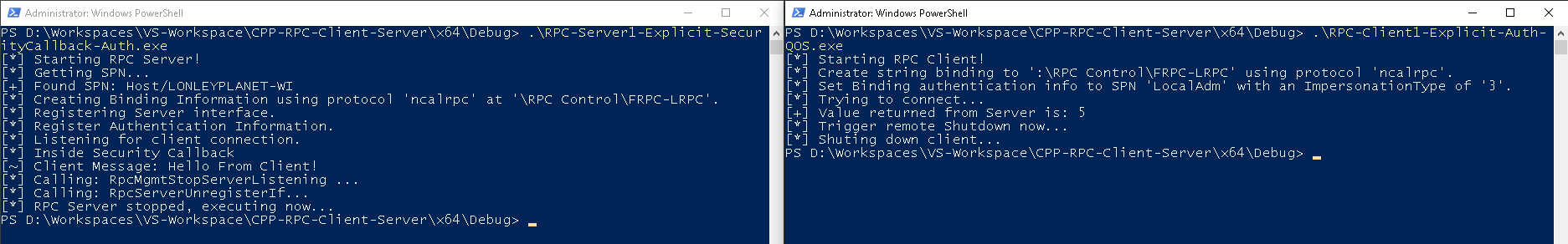

The below post will contain some references to code from my sample implementations, all of this code can be found here:

https://github.com/csandker/InterProcessCommunication-Samples/tree/master/RPC/CPP-RPC-Client-Server

History

Microsoft’s RPC implementation is based on the RPC implementation of the Distributed Computing Environment (DCE) standard developed by the Open Software Foundation (OSF) in 1993.

“One of the key companies that contributed [to the DCE implementation] was Apollo Computer, who brought in NCA – ‘Network Computing Architecture’ which became Network Computing System (NCS) and then a major part of DCE/RPC itself”

Source: https://kganugapati.wordpress.com/tag/msrpc/

Microsoft hired Paul Leach (in 1991), one of the founding Engineers of Apollo, which might be how RPC came into Windows.

Microsoft adjusted the DCE model to fit their programming scheme, based the communication of RPC on Named Pipes and brought their implementation to daylight in Windows 95.

Back in the days you could have wondered why they based the communication on Named Pipes, because Microsoft just came up with a new technology called Local Procedure Call (LPC) in 1994 and it sounds like it would have made sense to base a technology called Remote Procedure Call on something called Local Procedure call, right?… Well yes LPC would have been the logical choice (and I would guess they initially went with LPC), but LPC had a crucial flaw: It didn’t support (and still doesn’t) asynchronous calls (more on this when i finally finish my LPC/ALPC post…), which is why Microsoft based it on Named Pipes.

As we’ll see in a moment (section RPC Protocol Sequence) when implementing routines with RPC the developer needs to tell the RPC library what ‘protocol’ to use for transportation. The original DCE/RCP standard already had defined ‘ncacn_ip_tcp’ and ‘ncadg_ip_udp’ for TCP and UDP connections. Microsoft added ‘ncacn_np’ for their implementation based on Named Pipes (transported through the SMB protocol).

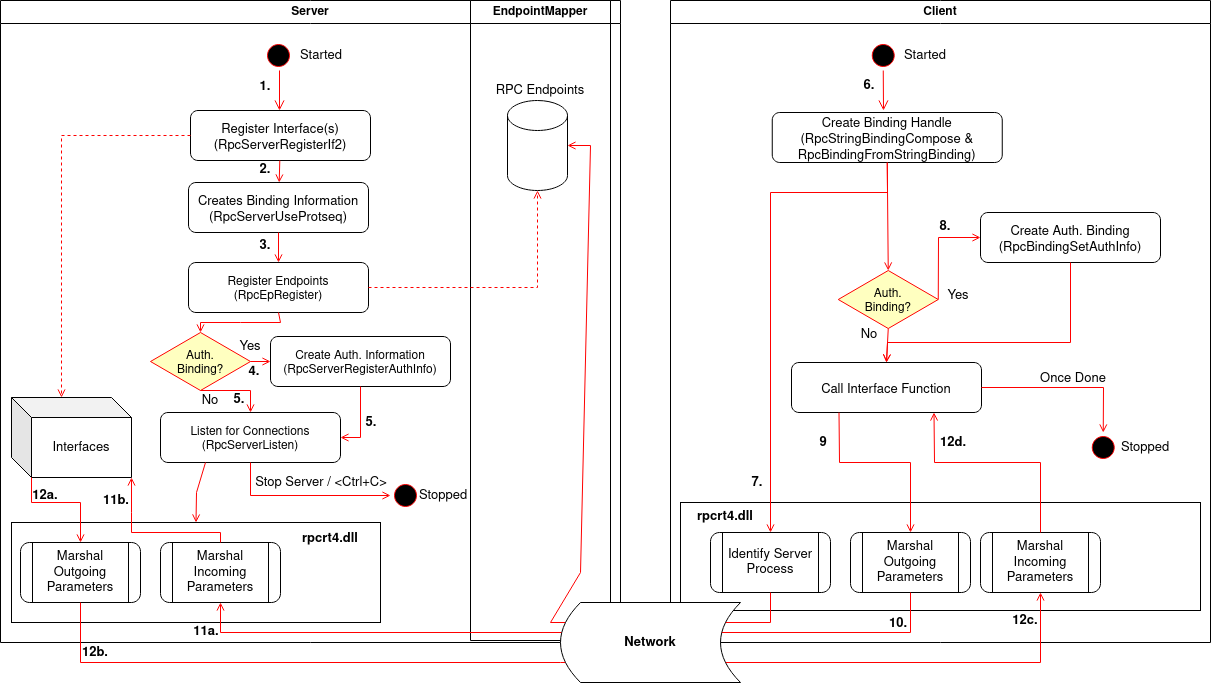

RPC Messaging

RPC is a client-server technology with messaging architecture similar to COM (Component Object Model), which on a high level consists of the following three components:

- A server & client process that are responsible for registering an RPC interface and associated binding information (more on this later on)

- Server & client stubs that are responsible for marshalling incoming and outgoing data

- The server’s & client’s RPC runtime library (rpcrt4.dll), which takes the stub data and sends them over the wire using the specified protocol (examples and details will follow)

A visual overview of this message architecture can be found at https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/rpc/how-rpc-works as shown below:

Later on, in section RPC Communication Flow, i will provide an overview of the steps involved from creating an RPC server to sending a message, but before we can dive into that we need to clarify a few RPC terminology bits.

Bare with me here while we dig into the insides of RPC. The following things are essential to know in order to to get along with RPC.

If you get lost in new terms and API calls that you just can’t get in line you can always jump ahead to the RPC Communication Flow section to get an idea of where these thing belong in the communication chain.

RPC Protocol Sequence

The RPC Protocol Sequence is a constant string that defines which protocol the RPC runtime should use to transfer messages.

This string defines which RPC protocol, transport and network protocol should be used.

Microsoft supports the following three RPC protocols:

- Network Computing Architecture connection-oriented protocol (NCACN)

- Network Computing Architecture datagram protocol (NCADG)

- Network Computing Architecture local remote procedure call (NCALRPC)

In most scenarios where a connection is made across system boundaries you will find NCACN, whereas NCALRPC is recommended for local RPC communication.

The protocol sequence is a defined constant string assembled from the above parts, e.g. ncacn_ip_tcp for a connection-oriented communication based on TCP packets.

The full list of RPC protocol sequence constants can be found at: https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/rpc/protocol-sequence-constants.

The most relevant protocol sequences are shown below:

| Constant/Value | Description |

|---|---|

| ncacn_ip_tcp | Connection-oriented Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol (TCP/IP) |

| ncacn_http | Connection-oriented TCP/IP using Microsoft Internet Information Server as HTTP proxy |

| ncacn_np | Connection-oriented named pipes (via SMB.) |

| ncadg_ip_udp | Datagram (connectionless) User Datagram Protocol/Internet Protocol (UDP/IP) |

| ncalrpc | Local Procedure Calls (post Windows Vista via ALPC) |

RPC Interfaces

In order to establish a communication channel the RPC runtime needs to know what methods (aka. “functions”) and parameters your server offers and what data your client is sending. These information are defined in a so called “Interface”.

Side note: If you’re familiar with interfaces in COM, this is the same thing.

To get an idea of how an interface could be defined, let’s take this example from my Sample Code:

Interface1.idl

[

// UUID: A unique identifier that distinguishes this

// interface from other interfaces.

uuid(9510b60a-2eac-43fc-8077-aaefbdf3752b),

// This is version 1.0 of this interface.

version(1.0),

// Using an implicit handle here named hImplicitBinding:

implicit_handle(handle_t hImplicitBinding)

]

interface Example1 // The interface is named Example1

{

// A function that takes a zero-terminated string.

int Output(

[in, string] const char* pszOutput);

void Shutdown();

}

The first thing to note is that interfaces are defined in an Interface Definition Language (IDL) file. The definitions in this will later on be compiled by the Microsoft IDL compiler (midl.exe) into header and source code files that can be used by the server and client.

The interface header is rather self explanatory with the given comments — ignore the implicit_handle instruction for now, we get into implicit and explicit handles shortly.

The body of the interface describes the methods that this interfaces exposes, their return values and their parameters. The [in, string] statement within parameter definition of the Output function is not mandatory but aids the understanding of what this parameter is used for.

Side note: You could also specify various interface attributes in an Application Configuration File (ACF). Some of these such as the type of binding (explicit vs. implicit) can be placed in the IDL file, but for more complex interfaces you might want to add an extra ACF file per interface.

RPC Binding

Once your client connects to an RPC server (we’ll get into how this is done later on) you create what Microsoft calls a “Binding”. Or to put it with Microsoft’s words:

Binding is the process of creating a logical connection between a client program and a server program. The information that composes the binding between client and server is represented by a structure called a binding handle.

The terminology of binding handles gets clearer once we put some context on it. Technically there three types of binding handles:

- Implicit

- Explicit

- Automatic

Side note: You could implement custom binding handles as described in here, but we ignore this for this post, as this is rather uncommon and you’re good with the default types.

Implicit binding handles allow your client to connect to and communicate with a specific RPC server (specified by the UUID in the IDL file). The downside is implicit bindings are not thread safe, multi-threaded applications should therefore use explicit bindings. Implicit binding handles are defined in the IDL file as shown in the sample IDL code above or in my Sample Implicit Interface.

Explicit binding handles allow your client to connect to and communicate with multiple RPC servers. Explicit binding handles are recommended to use due to being thread safe and allow for multiple connections. An example of an explicit binding handle definition can be found in my code here.

Automatic binding is a solution in between for the lazy developer, who doesn’t want to fiddle around with binding handles and let the RPC runtime figure out what is needed. My recommendation would be to use explicit handles just to be aware of what you’re doing.

Why do i need binding handles in the first place you might ask at this point.

Imagine a binding handle as a representation of your communication channel between client and server, just like the cord in a can phone (i wonder how many people know these ‘devices’…). Given that you have a representation of the communication chanel (‘the cord’) you can add attributes to this communication channel, like painting your cord to make it more unique.

Just like that binding handles allow you for example to secure the connection between your client and server (because you got something that you can add security to) and therefore form what Microsoft terms “authenticated” bindings.

Anonymous & Authenticated Bindings

Let’s say you’ve got a plain and simple RPC server running, now a client connects to your server. If you didn’t specify anything expect the bare minimum (which i will list shortly), this connection between client and server is referred to as anonymous or unauthenticated binding, due to the fact that your server got no clue who connected to it.

To avoid any client from connecting and to level up the security of your server there are three gears you can turn:

- You can set registration flags when registering your server interface; And/Or

- You can set a Security callback with a custom routine to check whether a requesting client should be allowed or denied; And/Or

- You can set authentication information associated with your binding handle to specify a security service provider and an SPN to represent your RPC server.

Let’s look at those three gears step-by-step.

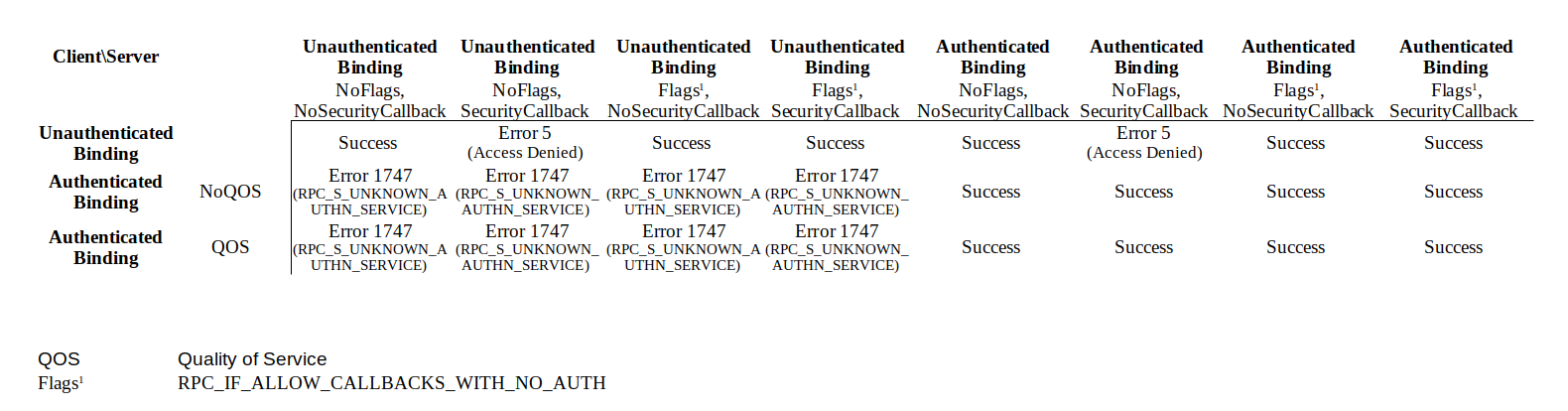

Registration Flags

First of all when you create your server you need to register your interface, for example with a call to RpcServerRegisterIf2 — I’ll show you where this call comes into play in section RPC Communication Flow. As a fourth parameter to RpcServerRegisterIf2 you can specify Interface Registration Flags, such as RPC_IF_ALLOW_LOCAL_ONLY to only allow local connections.

Side note: Read this as RPC_InterFace_ALLOW_LOCAL_ONLY

A sample call could look like this:

RPC_STATUS rpcStatus = RpcServerRegisterIf2(

Example1_v1_0_s_ifspec, // Interface to register.

NULL, // NULL type UUID

NULL, // Use the MIDL generated entry-point vector.

RPC_IF_ALLOW_LOCAL_ONLY, // Only allow local connections

RPC_C_LISTEN_MAX_CALLS_DEFAULT, // Use default number of concurrent calls.

(unsigned)-1, // Infinite max size of incoming data blocks.

NULL // No security callback.

);

Security Callbacks

Next on the list is the security callback, which you could set as the last parameter of the above call. An always-allow callback could look like this:

// Naive security callback.

RPC_STATUS CALLBACK SecurityCallback(RPC_IF_HANDLE hInterface, void* pBindingHandle)

{

return RPC_S_OK; // Always allow anyone.

}

To include this Security callback simply set the last parameter of the RpcServerRegisterIf2 function to the name of your security callback function, which in this case is just named “SecurityCallback”, as shown below:

RPC_STATUS rpcStatus = RpcServerRegisterIf2(

Example1_v1_0_s_ifspec, // Interface to register.

NULL, // Use the MIDL generated entry-point vector.

NULL, // Use the MIDL generated entry-point vector.

RPC_IF_ALLOW_LOCAL_ONLY, // Only allow local connections

RPC_C_LISTEN_MAX_CALLS_DEFAULT, // Use default number of concurrent calls.

(unsigned)-1, // Infinite max size of incoming data blocks.

SecurityCallback // No security callback.

);

This callback function can be implemented in any way you like, you could for example allow/deny connections based on IPs.

Authenticated Bindings

Alright we’re getting closer to the end of the RPC terminology and background section… Stay with me while we dig into the last concepts.

As I can feel the pain to follow up for people who are new to all these terms, let’s take a moment to recap:

Okay so far you should know that you can create implicit and explicit interfaces and use a few Windows API calls to setup your RPC server. In the previous section I’ve added that once you register your server you can set registration flags and (if you want to) also a callback function to secure you server and filter the clients who can access your server. The last piece in the puzzle is now an extra Windows API that allows the server and client to authenticate your binding (remember that one of the benefits of having a binding handle is that you can authenticate your binding, like ‘painting your cord for your can phone’).

… But why would/should you do that?

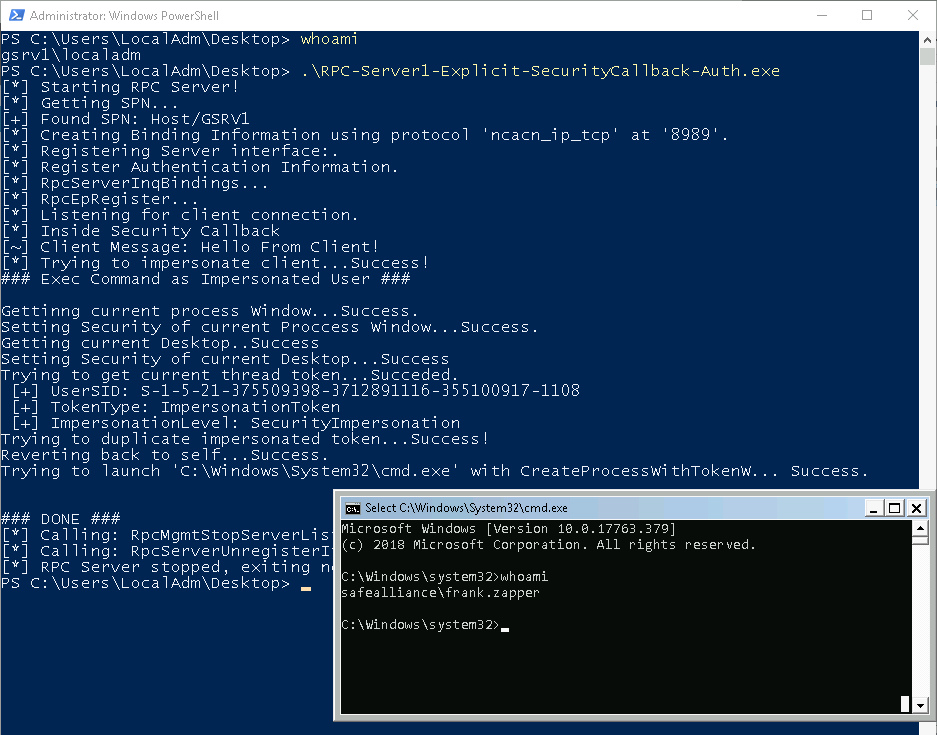

Authenticated Bindings in combination with the right registration flag (RPC_IF_ALLOW_SECURE_ONLY) enables your RPC Server to ensure that only authenticated users can connect; And — in case the client allows it — enables the server to figure out who connected to it by impersonating the client.

To backup what you learned before: You could as well use the SecurityCallback to deny any anonymous client from connecting, but you would need to implement the filter mechanism on your own, based on attributes you control.

Example: You wouldn’t be able to determine if the client is for example a valid domain user, because you don’t have any access to these account information.

Okay so how do you specify an authenticated binding?

You can authenticate your binding on the server and on the client side. On the server side you want to implement this to ensure a secured connection and on the client side you might need to have this in order to be able to connect to your server (as we’ll see shortly in the Access Matrix)

Authenticating the binding on the Server side: [Taken from my example code here]

RPC_STATUS rpcStatus = RpcServerRegisterAuthInfo(

pszSpn, // Server principal name

RPC_C_AUTHN_WINNT, // using NTLM as authentication service provider

NULL, // Use default key function, which is ignored for NTLM SSP

NULL // No arg for key function

);

Authenticating the binding on the client side: [Taken from my example code here]

RPC_STATUS status = RpcBindingSetAuthInfoEx(

hExplicitBinding, // the client's binding handle

pszHostSPN, // the server's service principale name (SPN)

RPC_C_AUTHN_LEVEL_PKT, // authentication level PKT

RPC_C_AUTHN_WINNT, // using NTLM as authentication service provider

NULL, // use current thread credentials

RPC_C_AUTHZ_NAME, // authorization based on the provided SPN

&secQos // Quality of Service structure

);

The interesting bit on the client side is that you can set a Quality of Service (QOS) structure with your authenticated binding handle. This QOS structure can for example be used on the client side to determine the Impersonation Level (for background information check out my previous IPC post ), which we’ll later cover in section Client Impersonation.

Important to note:

Setting an authenticated binding on the server side, does not enforce an authentication on the client side.

If for example no flags are set on the server side or only the RPC_IF_ALLOW_CALLBACKS_WITH_NO_AUTH is set, unauthenticated clients can still connect to the RPC server.

Setting the RPC_IF_ALLOW_SECURE_ONLY flag however prevents unauthenticated client bindings, because the client can’t set an authentication level (which is what is checked with this flag) without creating an authenticated binding.

Well-known vs Dynamic Endpoints

Last but not least we have to clarify one last important aspect of RPC communication: Well-known vs Dynamic endpoints.

I’ll try to make this one short as it’s also quite easy to understand…