These curl recipes show you how to make curl silent so that it doesn’t print progress bar, errors, and other output that can get in the way. To do that, use the -s argument. To also hide the response, use the -o /dev/null to discard the output (-o NUL on Windows).

- Hide Errors and Progress Bar (but Print Response)

- Make Curl Dead Silent

- Make Curl Dead Silent (but Print the Error)

Hide Errors and Progress Bar (but Print Response)

curl -s https://catonmat.net

In this recipe, curl uses the -s argument that hides all errors and the progress bar. If the request succeeds, then curl will still print the response body. If there was an error, then the only way to tell what it was is to check the exit code of the curl process. See the next recipe to see how to make dead silent curl requests.

Make Curl Dead Silent

curl -s -o /dev/null https://google.com

In this recipe, we combine the -s option that we used in the previous recipe with the -o /dev/null option. The combination of both of these options makes curl absolutely silent. The only way to tell if it succeeded or failed is to check the return code of the curl program. If it’s zero, then curl succeeded, otherwise it failed.

Make Curl Dead Silent (but Print the Error)

curl -S -s -o /dev/null https://google.com

This recipe adds the -S command line argument to the mix. When combined with the -s argument, it tells curl to be silent, except when there is an error. In that case, print the error. This recipe is useful when you want curl to be silent but still want to know why it failed.

Created by Browserling

These curl recipes were written down by me and my team at Browserling. We use recipes like this every day to get things done and improve our product. Browserling itself is an online cross-browser testing service powered by alien technology. Check it out!

Secret message: If you love my curl recipe, then I love you, too! Use coupon code CURLLING to get a discount at my company.

cURL is a command line tool and a library which can be used to receive and send data between a client and a server or any two machines connected over the internet. It supports a wide range of protocols like HTTP, FTP, IMAP, LDAP, POP3, SMTP and many more.

Due to its versatile nature, cURL is used in many applications and for many use cases. For example, the command line tool can be used to download files, testing APIs and debugging network problems. In this article, we shall look at how you can use the cURL command line tool to perform various tasks.

Install cURL

Linux

Most Linux distributions have cURL installed by default. To check whether it is installed on your system or not, type curl in your terminal window and press enter. If it isn’t installed, it will show a “command not found” error. Use the commands below to install it on your system.

For Ubuntu/Debian based systems use:

sudo apt update sudo apt install curl

For CentOS/RHEL systems, use:

sudo yum install curl

On the other hand, for Fedora systems, you can use the command:

sudo dnf install curl

MacOS

MacOS comes with cURL preinstalled, and it receives updates whenever Apple releases updates for the OS. However, in case you want to install the most recent version of cURL, you can install the curl Homebrew package. Once you install Homebrew, you can install it with:

brew install curl

Windows

For Windows 10 version 1803 and above, cURL now ships by default in the Command Prompt, so you can use it directly from there. For older versions of Windows, the cURL project has Windows binaries. Once you download the ZIP file and extract it, you will find a folder named curl-<version number>-mingw. Move this folder into a directory of your choice. In this article, we will assume our folder is named curl-7.62.0-win64-mingw, and we have moved it under C:\.

Next, you should add cURL’s bin directory to the Windows PATH environment variable, so that Windows can find it when you type curl in the command prompt. For this to work, you need to follow these steps:

- Open the “Advanced System Properties” dialog by running

systempropertiesadvancedfrom the Windows Run dialog (Windows key + R). - Click on the “Environment Variables” button.

- Double-click on “Path” from the “System variables” section, and add the path

C:\curl-7.62.0-win64-mingw\bin. For Windows 10, you can do this with the “New” button on the right. On older versions of Windows, you can type in;C:\curl-7.62.0-win64-mingw\bin(notice the semicolon at the beginning) at the end of the “Value” text box.

Once you complete the above steps, you can type curl to check if this is working. If everything went well, you should see the following output:

C:\Users\Administrator>curl curl: try 'curl --help' or 'curl --manual' for more information

cURL basic usage

The basic syntax of using cURL is simply:

curl <url>

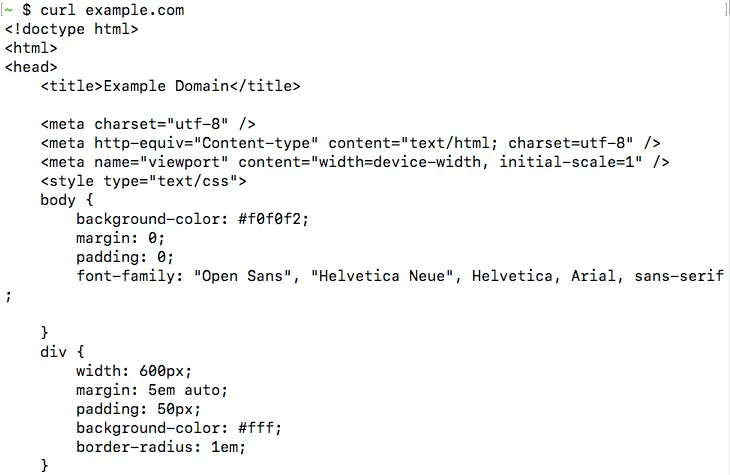

This fetches the content available at the given URL, and prints it onto the terminal. For example, if you run curl example.com, you should be able to see the HTML page printed, as shown below:

This is the most basic operation cURL can perform. In the next few sections, we will look into the various command line options accepted by cURL.

Downloading Files with cURL

As we saw, cURL directly downloads the URL content and prints it to the terminal. However, if you want to save the output as a file, you can specify a filename with the -o option, like so:

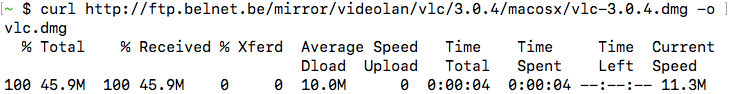

curl -o vlc.dmg http://ftp.belnet.be/mirror/videolan/vlc/3.0.4/macosx/vlc-3.0.4.dmg

In addition to saving the contents, cURL switches to displaying a nice progress bar with download statistics, such as the speed and the time taken:

Instead of providing a file name manually, you can let cURL figure out the filename with the -O option. So, if you want to save the above URL to the file vlc-3.0.4.dmg, you can simply use:

curl -O http://ftp.belnet.be/mirror/videolan/vlc/3.0.4/macosx/vlc-3.0.4.dmg

Bear in mind that when you use the -o or the -O options and a file of the same name exists, cURL will overwrite it.

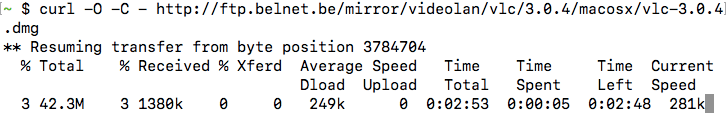

If you have a partially downloaded file, you can resume the file download with the -C - option, as shown below:

curl -O -C - http://ftp.belnet.be/mirror/videolan/vlc/3.0.4/macosx/vlc-3.0.4.dmg

Like most other command line tools, you can combine different options together. For example, in the above command, you could combine -O -C - and write it as -OC - .

Anatomy of a HTTP request/response

Before we dig deeper into the features supported by cURL, we will discuss a little bit about HTTP requests and responses. If you are familiar with these concepts, you directly skip to the other sections.

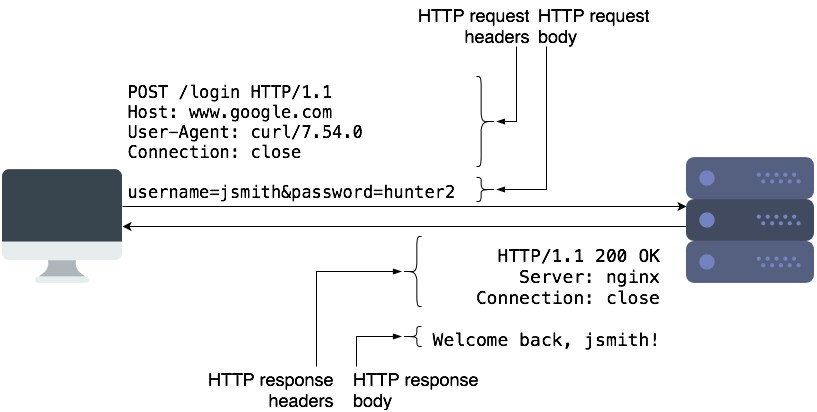

To request a resource such as a webpage, or to submit some data to a server, a HTTP client (such as a browser or cURL) makes a HTTP request to the server The server responds back with a HTTP response, which contains the “contents” of that page.

HTTP requests contain the request method, URL, some headers, and some optional data as part of the “request body”. The request method controls how a certain request should be processed. The most common types of request methods are “GET” and “POST”. Typically, we use “GET” requests to retrieve a resource from the server, and “POST” to submit data to the server for processing. “POST” requests typically contain some data in the request body, which the server can use.

HTTP responses are similar and contain the status code, some headers, and a body. The body contains the actual data that clients can display or save to a file. The status code is a 3-digit code which tells the client if the request succeeded or failed, and how it should proceed further. Common status codes are 2xx (success), 3xx (redirect to another page), and 4xx/5xx (for errors).

HTTP is an “application layer protocol”, and it runs over another protocol called TCP. It takes care of retransmitting any lost data, and ensures that the client and server transmit data at an optimal rate. When you use HTTPS, another protocol called SSL/TLS runs between TCP and HTTP to secure the data.

Most often, we use domain names such as google.com to access websites. Mapping the domain name to an IP address occurs through another protocol called DNS.

You should now have enough background to understand the rest of this article.

Following redirects with cURL

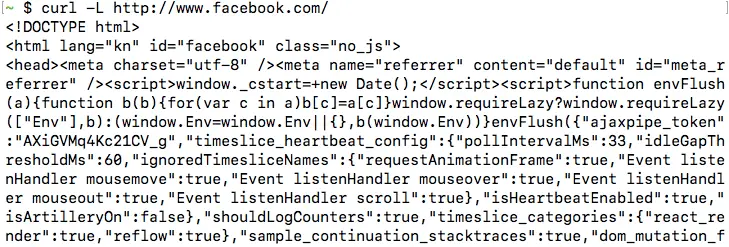

By default, when cURL receives a redirect after making a request, it doesn’t automatically make a request to the new URL. As an example of this, consider the URL http://www.facebook.com. When you make a request using to this URL, the server sends a HTTP 3XX redirect to https://www.facebook.com/. However, the response body is otherwise empty. So, if you try this out, you will get an empty output:

If you want cURL to follow these redirects, you should use the -L option. If you repeat make a request for http://www.facebook.com/ with the -L flag, like so:

curl -L http://www.facebook.com/

Now, you will be able to see the HTML content of the page, similar to the screenshot below. In the next section, we will see how we can verify that there is a HTTP 3XX redirect.

Please bear in mind that cURL can only follow redirects if the server replied with a “HTTP redirect”, which means that the server used a 3XX status code, and it used the “Location” header to indicate the new URL. cURL cannot process Javascript or HTML-based redirection methods, or the “Refresh header“.

If there is a chain of redirects, the -L option will only follow the redirects up to 500 times. You can control the number of maximum redirects that it will follow with the --max-redirs flag.

curl -L --max-redirs 700 example.com

If you set this flag to -1, it will follow the redirects endlessly.

curl -L --max-redirs -1 example.com

When debugging issues with a website, you may want to view the HTTP response headers sent by the server. To enable this feature, you can use the -i option.

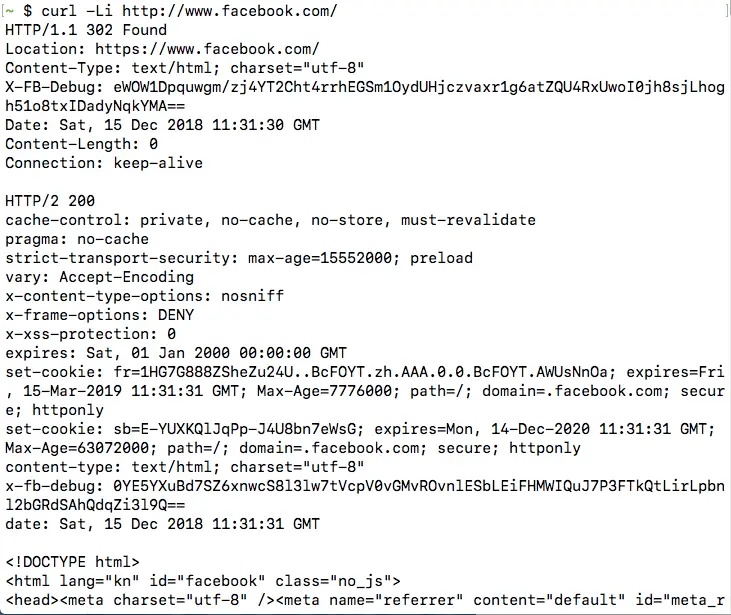

Let us continue with our previous example, and confirm that there is indeed a HTTP 3XX redirect when you make a HTTP request to http://www.facebook.com/, by running:

curl -L -i http://www.facebook.com/

Notice that we have also used -L so that cURL can follow redirects. It is also possible to combine these two options and write them as -iL or -Li instead of -L -i.

Once you run the command, you will be able to see the HTTP 3XX redirect, as well as the page HTTP 200 OK response after following the redirect:

If you use the -o/-O option in combination with -i, the response headers and body will be saved into a single file.

Viewing request headers and connection details

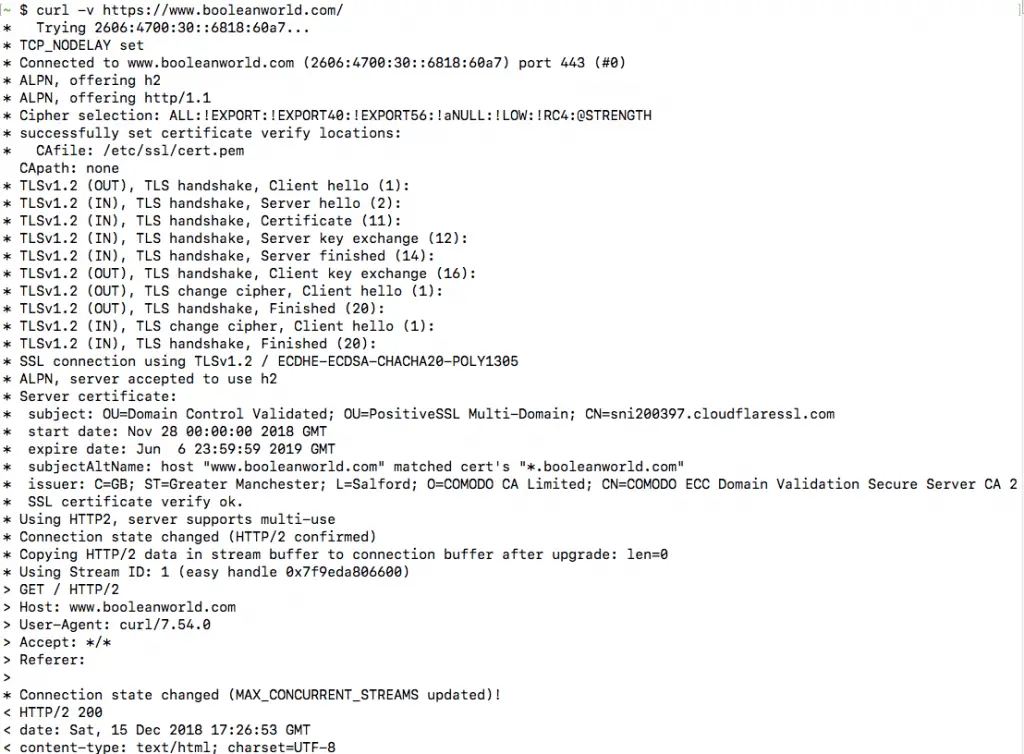

In the previous section, we have seen how you can view HTTP response headers using cURL. However, sometimes you may want to view more details about a request, such as the request headers sent and the connection process. cURL offers the -v flag (called “verbose mode”) for this purpose, and it can be used as follows:

curl -v https://www.booleanworld.com/

The output contains request data (marked with >), response headers (marked with <) and other details about the request, such as the IP used and the SSL handshake process (marked with *). The response body is also available below this information. (However, this is not visible in the screenshot below).

Most often, we aren’t interested in the response body. You can simply hide it by “saving” the output to the null device, which is /dev/null on Linux and MacOS and NUL on Windows:

curl -vo /dev/null https://www.booleanworld.com/ # Linux/MacOS curl -vo NUL https://www.booleanworld.com/ # Windows

Silencing errors

Previously, we have seen that cURL displays a progress bar when you save the output to a file. Unfortunately, the progress bar might not be useful in all circumstances. As an example, if you hide the output with -vo /dev/null, a progress bar appears which is not at all useful.

You can hide all these extra outputs by using the -s header. If we continue with our previous example but hide the progress bar, then the commands would be:

curl -svo /dev/null https://www.booleanworld.com/ # Linux/MacOS curl -svo NUL https://www.booleanworld.com/ # Windows

The -s option is a bit aggressive, though, since it even hides error messages. For your use case, if you want to hide the progress bar, but still view any errors, you can combine the -S option.

So, if you are trying to save cURL output to a file but simply want to hide the progress bar, you can use:

curl -sSvo file.html https://www.booleanworld.com/

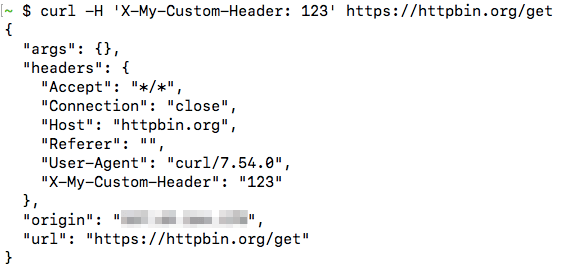

When testing APIs, you may need to set custom headers on the HTTP request. cURL has the -H option which you can use for this purpose. If you want to send the custom header X-My-Custom-Header with the value of 123 to https://httpbin.org/get, you should run:

curl -H 'X-My-Custom-Header: 123' https://httpbin.org/get

(httpbin.org is a very useful website that allows you to view details of the HTTP request that you sent to it.)

The data returned by the URL shows that this header was indeed set:

You can also override any default headers sent by cURL such as the “User-Agent” or “Host” headers. The HTTP client (in our case, cURL) sends the “User-Agent” header to tell the server about the type and version of the client used. Also, the client uses the “Host” header to tell the server about the site it should serve. This header is needed because a web server can host multiple websites at a single IP address.

Also, if you want to set multiple headers, you can simply repeat the -H option as required.

curl -H 'User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0' -H 'Host: www.google.com' ...

However, cURL does have certain shortcuts for frequently used flags. You can set the “User-Agent” header with the -A option:

curl -A Mozilla/5.0 http://httpbin.org/get

The “Referer” header is used to tell the server the location from which they were referred to by the previous site. It is typically sent by browsers when requesting Javascript or images linked to a page, or when following redirects. If you want to set a “Referer” header, you can use the -e flag:

curl -e http://www.google.com/ http://httpbin.org/get

Otherwise, if you are following a set of redirects, you can simply use -e ';auto' and cURL will take care of setting the redirects by itself.

Making POST requests with cURL

By default, cURL sends GET requests, but you can also use it to send POST requests with the -d or --data option. All the fields must be given as key=value pairs separated by the ampersand (&) character. As an example, you can make a POST request to httpbin.org with some parameters:

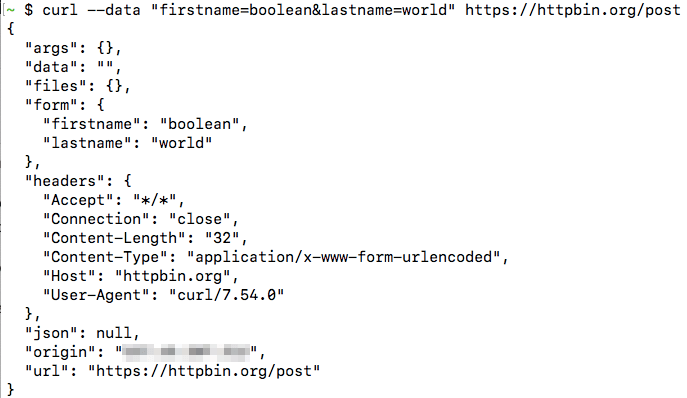

curl --data "firstname=boolean&lastname=world" https://httpbin.org/post

From the output, you can easily tell that we posted two parameters (this appears under the “form” key):

Any special characters such as @, %, = or spaces in the value should be URL-encoded manually. So, if you wanted to submit a parameter “email” with the value “[email protected]”, you would use:

curl --data "email=test%40example.com" https://httpbin.org/post

Alternatively, you can just use --data-urlencode to handle this for you. If you wanted to submit two parameters, email and name, this is how you should use the option:

curl --data-urlencode "[email protected]" --data-urlencode "name=Boolean World" https://httpbin.org/post

If the --data parameter is too big to type on the terminal, you can save it to a file and then submit it using @, like so:

curl --data @params.txt example.com

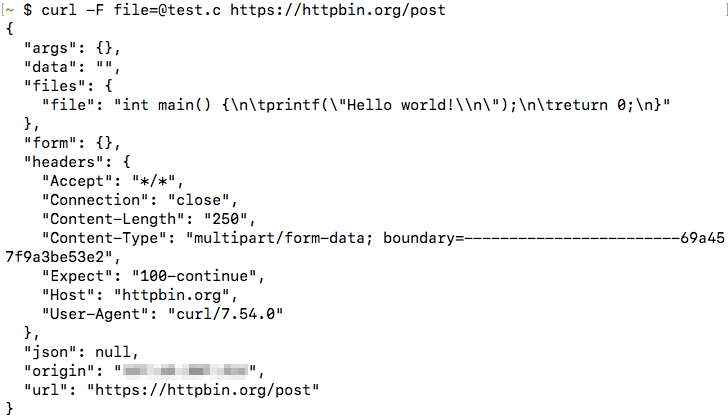

So far, we have seen how you can make POST requests using cURL. If you want to upload files using a POST request, you can use the -F (“form”) option. Here, we will submit the file test.c, under the parameter name file:

curl -F [email protected] https://httpbin.org/post

This shows the content of the file, showing that it was submitted successfully:

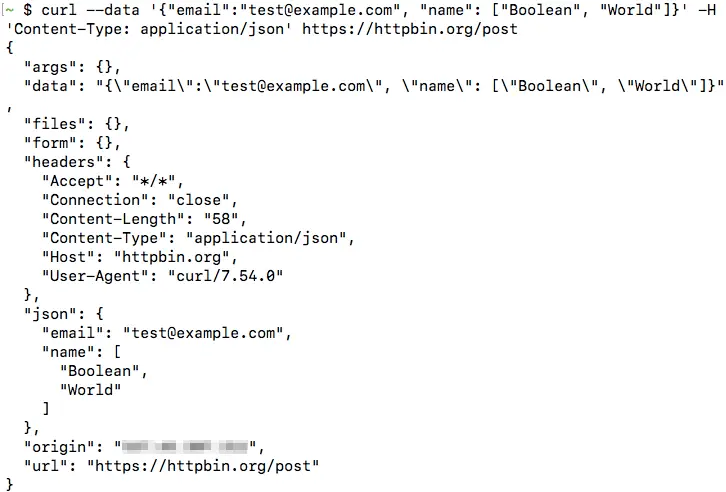

Submitting JSON data with cURL

In the previous section, we have seen how can submit POST requests using cURL. You can also submit JSON data using the --data option. However, most servers expect to receive a POST request with key-value pairs, similar to the ones we have discussed previously. So, you need to add an additional header called ‘Content-Type: application/json’ so that the server understands it’s dealing with JSON data and handles it appropriately. Also, you don’t need to URL-encode data when submitting JSON.

So if you had the following JSON data and want to make a POST request to https://httpbin.org/post:

{

"email": "[email protected]",

"name": ["Boolean", "World"]

}

Then, you can submit the data with:

curl --data '{"email":"[email protected]", "name": ["Boolean", "World"]}' -H 'Content-Type: application/json' https://httpbin.org/post

In this case, you can see the data appear under the json value in the httpbin.org output:

You can also save the JSON file, and submit it in the same way as we did previously:

curl --data @data.json https://httpbin.org/post

Changing the request method

Previously, we have seen how you can send POST requests with cURL. Sometimes, you may need to send a POST request with no data at all. In that case, you can simply change the request method to POST with the -X option, like so:

curl -X POST https://httpbin.org/post

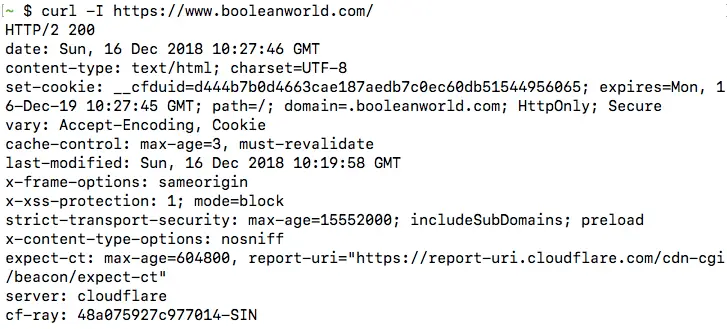

You can also change the request method to anything else, such as PUT, DELETE or PATCH. One notable exception is the HEAD method, which cannot be set with the -X option. The HEAD method is used to check if a document is present on the server, but without downloading the document. To use the HEAD method, use the -I option:

curl -I https://www.booleanworld.com/

When you make a HEAD request, cURL displays all the request headers by default. Servers do not send any content when they receive a HEAD request, so there is nothing after the headers:

Replicating browser requests with cURL

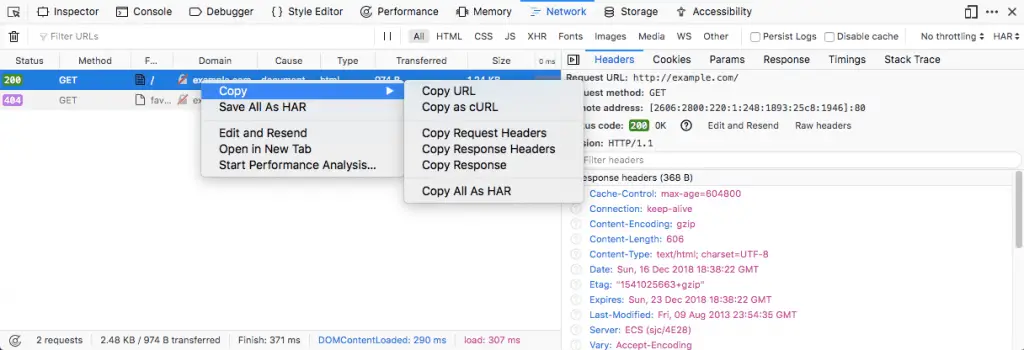

If you want to replicate a request made through your browser through cURL, you can use the Chrome, Firefox and Safari developer tools to get a cURL command to do so.

The steps involved are the same for all platforms and browsers:

- Open developer tools in Firefox/Chrome (typically F12 on Windows/Linux and Cmd+Shift+I on a Mac)

- Go to the network tab

- Select the request from the list, right click it and select “Copy as cURL”

The copied command contains all the headers, request methods, cookies etc. needed to replicate the exact same request. You can paste the command in your terminal to run it.

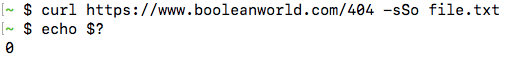

Making cURL fail on HTTP errors

Interestingly, cURL doesn’t differentiate between a successful HTTP request (2xx) and a failed HTTP request (4xx/5xx). So, it always returns an exit status of 0 as long as there was no problem connecting to the site. This makes it difficult to write shell scripts because there is no way to check if the file could be downloaded successfully.

You can check this by making a request manually:

curl https://www.booleanworld.com/404 -sSo file.txt

You can see that curl doesn’t print any errors, and the exit status is also zero:

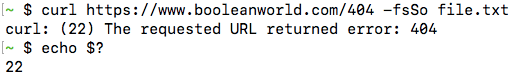

If you want to consider these HTTP errors as well, you can use the -f option, like so:

curl https://www.booleanworld.com/404 -fsSo file.txt

Now, you can see that cURL prints an error and also sets the status code to 22 to inform that an error occured:

Making authenticated requests with cURL

Some webpages and APIs require authentication with an username and password. There are two ways to do this. You can mention the username and password with the -u option:

curl -u boolean:world https://example.com/

Alternatively, you can simply add it to the URL itself, with the <username>:<password>@<host> syntax, as shown:

curl https://boolean:[email protected]/

In both of these methods, curl makes a “Basic” authentication with the server.

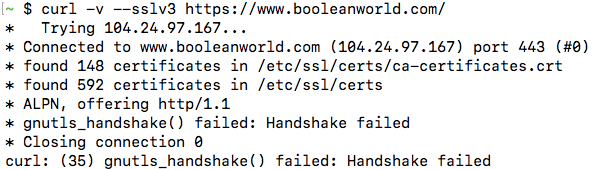

Testing protocol support with cURL

Due to the wide range of protocols supported by cURL, you can even use it to test protocol support. If you want to check if a site supports a certain version of SSL, you can use the --sslv<version> or --tlsv<version> flags. For example, if you want to check if a site supports TLS v1.2, you can use:

curl -v --tlsv1.2 https://www.booleanworld.com/

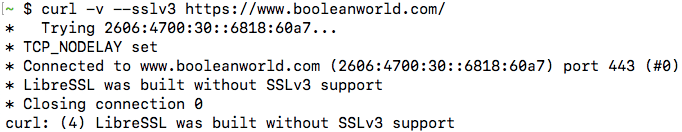

The request takes place normally, which means that the site supports TLSv1.2. Now, let us check if the site supports SSL v3:

curl -v --sslv3 https://www.booleanworld.com/

This command throws a handshake_failed error, because the server doesn’t support this version of SSL.

Please note that, depending on your system and the library version/configuration, some of these version options may not work. The above output was taken from Ubuntu 16.04’s cURL. However, if you try this with cURL in MacOS 10.14, it gives an error:

You can also test for HTTP protocol versions in the same way, by using the flags --http1.0, --http1.1 or --http2.

Setting the Host header and cURL’s --resolve option

Previously, we have discussed about how a web server chooses to serve different websites to visitors depending upon the “Host” header. This can be very useful to check if your website has virtual hosting configured correctly, by changing the “Host” header. As an example, say you have a local server at 192.168.0.1 with two websites configured, namely example1.com and example2.com. Now, you can test if everything is configured correctly by setting the Host header and checking if the correct contents are served:

curl -H 'Host: example1.com' http://192.168.0.1/ curl -H 'Host: example1.com' http://192.168.0.1/

Unfortunately, this doesn’t work so well for websites using HTTPS. A single website may be configured to serve multiple websites, with each website using its own SSL/TLS certificate. Since SSL/TLS takes place at a lower level than HTTP, this means clients such as cURL have to tell the server which website we’re trying to access at the SSL/TLS level, so that the server can pick the right certificate. By default, cURL always tells this to the server.

However, if you want to send a request to a specific IP like the above example, the server may pick a wrong certificate and that will cause the SSL/TLS verification to fail. The Host header only works at the HTTP level and not the SSL/TLS level.

To avoid the problem described above, you can use the --resolve flag. The resolve flag will send the request to the port and IP of your choice but will send the website name at both SSL/TLS and HTTP levels correctly.

Let us consider the previous example. If you were using HTTPS and wanted to send it to the local server 192.168.0.1, you can use:

curl https://example1.com/ --resolve example1.com:192.168.0.1:443

It also works well for HTTP. Suppose, if your HTTP server was serving on port 8080, you can use either the --resolve flag or set the Host header and the port manually, like so:

curl http://192.168.0.1:8080/ -H 'Host: example1.com:8080' curl http://example.com/ --resolve example1.com:192.168.0.1:8080

The two commands mentioned above are equivalent.

Resolve domains to IPv4 and IPv6 addresses

Sometimes, you may want to check if a site is reachable over both IPv4 or IPv6. You can force cURL to connect to either the IPv4 or over IPv6 version of your site by using the -4 or -6 flags.

Please bear in mind that a website can be reached over IPv4 and IPv6 only if:

- There are appropriate DNS records for the website that links it to IPv4 and IPv6 addresses.

- You have IPv4 and IPv6 connectivity on your system.

For example, if you want to check if you can reach the website icanhazip.com over IPv6, you can use:

curl -6 https://icanhazip.com/

If the site is reachable over HTTPS, you should get your own IPv6 address in the output. This website returns the public IP address of any client that connects to it. So, depending on the protocol used, it displays an IPv4 or IPv6 address.

You can also use the -v option along with -4 and -6 to get more details.

Disabling cURL’s certificate checks

By default, cURL checks certificates when it connects over HTTPS. However, it is often useful to disable the certificate checking, when you are trying to make requests to sites using self-signed certificates, or if you need to test a site that has a misconfigured certificate.

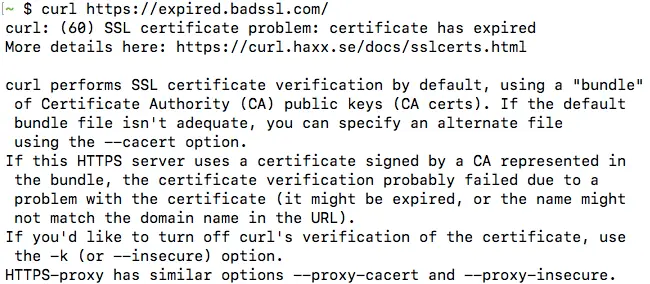

To disable certificate checks, use the -k certificate. We will test this by making a request to expired.badssl.com, which is a website using an expired SSL certificate.

curl -k https://expired.badssl.com/

With the -k option, the certificate checks are ignored. So, cURL downloads the page and displays the request body successfully. On the other hand, if you didn’t use the -k option, you will get an error, similar to the one below:

Troubleshooting website issues with “cURL timing breakdown”

You may run into situations where a website is very slow for you, and you would like to dig deeper into the issue. You can make cURL display details of the request, such as the time taken for DNS resolution, establishing a connection etc. with the -w option. This is often called as a cURL “timing breakdown”.

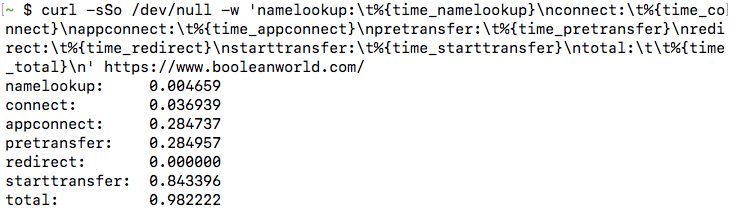

As an example, if you want to see these details for connecting to https://www.booleanworld.com/, run:

curl https://www.booleanworld.com/ -sSo /dev/null -w 'namelookup:\t%{time_namelookup}\nconnect:\t%{time_connect}\nappconnect:\t%{time_appconnect}\npretransfer:\t%{time_pretransfer}\nredirect:\t%{time_redirect}\nstarttransfer:\t%{time_starttransfer}\ntotal:\t\t%{time_total}\n'

(If you are running this from a Windows system, change the /dev/null to NUL).

You will get some output similar to this:

Each of these values is in seconds, and here is what each value represents:

- namelookup — The time required for DNS resolution.

- connect — The time required to establish the TCP connection.

- appconnect — This is the time taken to establish connections for any layers between TCP and the application layer, such as SSL/TLS. In our case, the application layer is HTTP. Also, if there is no such intermediate layer (such as when there is a direct HTTP request), this time will always be 0.

- pretransfer — This is the time taken from the start to when the transfer of the file is just about to begin.

- redirect — This is the total time taken to process any redirects.

- starttransfer — Time it took from the start to when the first byte is about to be transferred.

- total — The total time taken for cURL to complete the entire process.

As an example, say, you are facing delays connecting to a website and you notice the “namelookup” value was too high. As this indicates a problem with your ISP’s DNS server, you may start looking into why the DNS lookup is so slow, and switch to another DNS server if needed.

cURL configuration files

Sometimes, you may want to make all cURL requests use the same options. Passing these options by hand isn’t a feasible solution, so cURL allows you to specify options in a configuration file.

The default configuration file is located in ~/.curlrc in Linux/MacOS and %appdata%\_curlrc in Windows. Inside this file, you can specify any options that you need, such as:

# Always use IPv4 -4 # Always show verbose output -v # When following a redirect, automatically set the previous URL as referer. referer = ";auto" # Wait 60 seconds before timing out. connect-timeout = 60

After creating the above file, try making a request with curl example.com. You will find that these options have taken effect.

If you want to use a custom configuration file instead of the default one, then you can use -K option to point curl to your configuration file. As an example, if you have a configuration file called config.txt, then you can use it with:

curl -K config.txt example.com

Conclusion

In this article, we have covered the most common uses of the cURL command. Of course, this article only scratches the surface and cURL can do a whole lot of other things. You can type man curl in your terminal or just visit this page to see the man page which lists all the options.

Curl — Suppress output using the -o or —output /dev/null option

Let’s say the following curl command display the content of the index.html page on the www.example.com web server.

~]# curl http://www.example.com/index.html

<html>

<body>

Hello World

</body>

</html>The curl command with the -o /dev/null option can be used to suppress the response body output. Something like this should be displayed.

~]# curl -o /dev/null http://www.example.com/index.html

% Total % Received % Xferd Average Speed Time Time Time Current

Dload Upload Total Spent Left Speed

0 24 0 24 0 0 380 0 --:--:-- --:--:-- --:--:-- 727If you also want to supress the progress bar, the -s or —silent flag can be used.

~]# curl --silent -o /dev/null http://www.example.com/index.htmlNow the curl command returns no output. This is typically used when you want to:

- Display the HTTP response code

Did you find this article helpful?

If so, consider buying me a coffee over at

cURL is a command-line utility and a library for receiving and sending data between a client and a server, or any two machines connected via the internet. HTTP, FTP, IMAP, LDAP, POP3, SMTP, and a variety of other protocols are supported.

cURL is a project with the primary goal of creating two products:

- curl is a command-line tool

- libcurl is a C-based transfer library

Both the tool and the library use Internet protocols to transport resources given as URLs.

Curl is in charge of anything and anything that has to do with Internet protocol transfers. Things unrelated to that should be avoided and secured for other initiatives and products.

It’s also worth remembering that curl and libcurl aim to avoid handling the actual data being sent. It knows nothing about HTML or any other type of content that is commonly transferred over HTTP, but it understands all there is to know about transferring data over HTTP.

Both products are frequently used for server testing, protocol fiddling, and trying out new things, in addition to driving thousands or millions of scripts and applications for an Internet-connected society. With its versatility, cURL is utilized in a wide range of applications and scenarios.

We’ll look at how to utilize the UNIX cURL command line to conduct various tasks in this tutorial.

- Set Up First

- cURL Simple Command Usage

- Downloading Files

- Following Redirects

- Viewing Response Headers

- View Request Headers and Connection Information

- Silencing Errors

- Setting HTTP Request Headers

- Make POST Requests

- Submit JSON Data

- Change the Request Method

- Making cURL Fail on HTTP Errors

- Make Authenticated Requests

- Testing Protocol Support

- Setting the Host Header

- cURL’s —resolve Flag

- Resolve Domains to IPv4 and IPv6 Addresses

- Disabling cURL’s Certificate Checks

- cURL Configuration Files

#1 Set Up First

macOS

cURL is preloaded on macOS and receives upgrades whenever Apple publishes new versions of the operating system. You can, however, install the curl Homebrew package if you want to install the most latest version of cURL. You can use the following commands to install Homebrew:

brew install curlWindows

Since version 1804 of Windows 10, the curl tool has been included as part of the operating system. Download and install the newest official curl release for Windows from curl.se/windows if you have an older Windows version or simply want to upgrade to the latest version delivered by the curl project.

You’ll discover a folder titled curl-<version number>-mingw once you’ve downloaded and extracted the ZIP file. Place this folder in a location of your choosing. We’ll assume that our folder is called curl-7.98.0-win64-mingw and that it’s located on C:\.

The bin directory of cURL should then be added to the Windows PATH environment variable so that Windows can discover it when you run curl on the command prompt. You must take the following steps for this to work:

- Run systempropertiesadvanced from the Windows Run dialogue (Windows key + R) to open the «Advanced System Properties» window.

- Select “Environment Variables”.

- Add the path C:\curl-7.98.0-win64-mingw\bin by double-clicking on “Path” in the “System variables” section. This may be done in Windows 10 by pressing the right-hand “New” button. You can enter ;C:\curl-7.98.0-win64-mingw\bin (note the semicolon at the beginning) at the end of the “Value” text box on previous versions of Windows.

After you’ve completed the preceding steps, use curl to see if it’s working. If everything went well, you should be able to see something similar to this:

C:\Users\Administrator> curlLinux

cURL is installed by default on most Linux distributions. Type curl into your terminal window and press enter to see if it’s installed on your machine. It will display a “command not found” message if it is not installed. To install it on your machine, run the steps listed below.

Use the following for Ubuntu/Debian-based systems:

sudo apt update

sudo apt install curlFor CentOS/RHEL systems:

sudo yum install curlFor Fedora systems:

sudo dnf install curl#2 cURL Simple Command Usage

The following is the basic syntax for using cURL:

curl <url>This retrieves the content from the specified URL and prints it to the terminal.

At funet’s ftp-server, get the README file in the user’s home directory:

curl ftp://ftp.funet.fi/READMEUsing port 8000, retrieve a web page from a server:

curl http://www.weirdserver.com:8000/Obtain an FTP site’s directory listing:

curl ftp://ftp.funet.fiUse a dictionary to look up the meaning of curl:

curl dict://dict.org/m:curlThis is the most basic action that cURL can take. We’ll look at the many command-line functions that cURL accepts in the following sections.

#3 Downloading Files

As we’ve seen, cURL downloads the content of a URL and publishes it to the terminal. If you want to save the output as a file, use the -o option to provide a filename, such as:

curl -o vlc.dmg

http://ftp.belnet.be/mirror/videolan/vlc/3.0.4/macosx/vlc-3.0.4.dmgcURL switches to displaying a lovely progress bar with download information, such as the speed and time taken, in addition to saving the contents.

You can use the -O option to let cURL figure out the filename instead of manually giving one. So, if you want to save the above URL to the vlc-3.0.4.dmg file, just type:

curl -O http://ftp.belnet.be/mirror/videolan/vlc/3.0.4/macosx/vlc-3.0.4.dmgIf you use the -o or -O options and a file with the same name already exists, cURL will overwrite it.

If you have a partially downloaded file, use the -C — option to resume the download, as demonstrated below:

curl -O -C - http://ftp.belnet.be/mirror/videolan/vlc/3.0.4/macosx/vlc-3.0.4.dmgYou may combine different options, just like with most other command-line tools. You could, for example, combine -O -C — and write it as -OC — in the above command.

#4 Following Redirects

When cURL gets a redirect after a request, it does not initiate a request to the new URL by default. Consider the online cURL test URL http://www.instagram.com as an example. The server sends an HTTP 3XX redirect to https://www.instagram.com/ when you make a request using this URL. The response body, on the other hand, is completely empty.

The -L option should be used if you wish cURL to follow these redirects. Make a request for http://www.instagram.com/ with the -L flag again, as follows:

curl -L http://www.instagram.com/Please keep in mind that cURL can only follow redirects if the server returned an «HTTP redirect» response, which means the server used a 3XX status code and the «Location» header to identify the new URL. Javascript or HTML-based redirection mechanisms, as well as the «Refresh header,» are not supported by cURL.

When troubleshooting a website, look at the HTTP response headers given by the server. The -i option can be used to enable this feature.

Let’s stick with our prior example and see if there is an HTTP 3XX redirect when you go to http://www.instagram.com/ by running:

curl -L -i http://www.instagram.com/It’s worth noting that we also used -L to allow cURL to track redirects. Instead of -L -i, you can combine these two options and write them as -iL or -Li.

The response headers and body will be stored in a single file if you use the -o/-O option in combination with -i.

#6 View Request Headers and Connection Information

We saw how to use cURL to inspect HTTP response headers in the previous section. However, you may wish to see more information about a request, such as the request headers sent and the connection procedure, on occasion. For this, cURL provides the -v flag (sometimes known as «verbose mode«), which can be used as follows:

curl -v https://www.atatus.com/Request data, response headers, and other information about the request, such as the IP used and the SSL handshake process, are all included in the output.

Most of the time, we aren’t interested in the body of the cURL show response. Simply “save” the output to the null device, which on Linux and macOS is /dev/null and on Windows is NUL.

curl -vo /dev/null https://www.atatus.com/ # Linux/MacOS

curl -vo NUL https://www.atatus.com/ # Windows#7 Silencing Errors

When you save the output to a file, cURL displays a progress bar, as we’ve seen before. Unfortunately, the progress bar may not be appropriate in many situations. When you use -vo /dev/null to hide the output, for example, a progress bar shows, which is completely useless.

Using the -s header, you can hide all of these extra outputs. If we go with our prior example but remove the progress indicator, the commands are as follows:

curl -svo /dev/null https://www.atatus.com/ # Linux/MacOS

curl -svo NUL https://www.atatus.com/ # WindowsThe -s option, on the other hand, is a little overbearing, as it even hides error messages. If you wish to conceal the progress bar but still see any errors, you can combine the -S option with your use case.

If you merely want to conceal the progress indicator while saving cURL output to a file, you can use:

curl -sSvo file.html https://www.atatus.com/You may need to set special headers on HTTP requests while testing APIs. The -H option in cURL can be used for this purpose. You should run the following command to transmit the custom header X-My-Custom-Header with the value 123 to https://httpbin.org/get:

curl -H 'X-My-Custom-Header: 123' https://httpbin.org/gethttpbin.org is a very helpful website that allows you to see the specifics of each HTTP request you’ve made to it.

The data provided by the URL confirms that this header was set.

You can also override any of cURL’s default headers, such as the «User-Agent» and «Host» headers.

- The “User-Agent” header is sent by the HTTP client (in our example, cURL) to inform the server about the type and version of the client being used.

- The “Host” header is also used by the client to inform the server about the site it should serve. Since a web server might host numerous websites at the same IP address, this header is required.

You can also repeat the -H option as needed if you wish to set numerous headers.

curl -H 'User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0' -H 'Host: www.instagram.com' https://www.instagram.com/cURL, on the other hand, has a few shortcuts for commonly used flags. The «User-Agent» header can be set with the -A option:

curl -A Mozilla/5.0 http://httpbin.org/getThe “Referer” header is used to inform the server of where they were referred from the previous site. Browsers like google chrome send it when they request Javascript or images linked to a page, or when they follow redirects. The -e flag can be used to provide a «Referer» header:

curl -e https://www.instagram.com/ https://httpbin.org/getAnd if you’re following a series of redirects, simply use -e ‘;auto’, and cURL will handle the redirects for you.

#9 Make POST Requests

cURL sends GET requests by default, but you can use the -d or —data options to send POST requests. The ampersand (&) character must be used to separate all of the fields as key=value pairs. Make a POST request to httpbin.org with the following arguments, for example:

curl --data "firstname=atatus" https://httpbin.org/postAny special characters in the value, such as @, %, =, or spaces, should be manually URL-encoded. So, if you wanted to enter the value «test@example.com» for the argument «email,» you’d use:

curl --data "email=test%40example.com" https://httpbin.org/postYou may also use —data-urlencode to take care of this for you. This is how you should use the option if you wanted to input two arguments, email, and name:

curl --data-urlencode "email=test@example.com" --data-urlencode "name=atatus" https://httpbin.org/postIf the —data option is too long to type in on the terminal, save it to a file and submit it with @:

curl --data @params.txt example.comSo far, we’ve seen how to use cURL to make POST requests. Use the -F (“form”) option if you want to upload files using a POST request. We’ll send the file test.c here, with the parameter name file:

curl -F file=@test.c https://httpbin.org/post#10 Submit JSON Data

We saw how to use cURL to submit POST requests in the previous section. You can also use the —data option to input JSON data. Most servers, on the other hand, anticipate receiving a POST request with key=value pairs similar to the ones we mentioned earlier.

As a result, you’ll need to add a header named «Content-Type: application/json» to ensure that the server recognizes that it’s working with JSON data and responds accordingly. When uploading JSON, you also don’t need to URL-encode the data.

So, suppose you wish to send a POST request to https://httpbin.org/post with the following JSON data:

{

"email": "test@example.com",

"name": [ "atatus" ]

}After that, send the data to:

curl --data '{"email":"test@example.com", "name": ["atatus"]}' -H 'Content-Type: application/json' https://httpbin.org/postIn the httpbin.org output, the data appears beneath the JSON value.

You may alternatively save the JSON file and submit it using the same method as before:

curl --data @data.json https://httpbin.org/post#11 Change the Request Method

We’ve already seen how to use cURL to send POST requests. You may need to send a POST request with no data at all on occasion. In that scenario, simply use the -X option to change the request method to POST, as seen below:

curl -X POST https://httpbin.org/postYou can also alter the method of the request to anything other, like PUT, DELETE, or PATCH. The HEAD method is one significant example, as it cannot be set using the -X option. The HEAD method is used to see if a document is available on the server without having to download it. Use the -I option to use the HEAD method:

curl -I https://www.atatus.com/When you make a HEAD request, cURL automatically displays all of the request headers. When servers get a HEAD request, they do not send any content, therefore there is nothing after the headers.

#12 Making cURL Fail on HTTP Errors

Interestingly, cURL does not distinguish between a successful (2xx) and an unsuccessful (4xx/5xx) HTTP request.

Learn more about HTTP Status code — A Complete Guide to Understand HTTP Status Codes

As a result, if there was no trouble connecting to the site, it always returns a 0 (zero) exit status. This makes creating shell scripts difficult because there is no method to check if the file was correctly downloaded.

You can manually verify this by submitting the following request:

curl https://www.atatus.com/404 -sSo file.txtIf you wish to take into account certain HTTP errors as well, use the -f option, as follows:

curl https://www.atatus.com/404 -fsSo file.txt

#13 Make Authenticated Requests

Some websites and APIs require login and password authentication. There are two options for accomplishing this. With the -u option, you can specify the username and password:

curl -u atatus:@t@tus https://example.com/Alternatively, you can simply include it in the URL itself, using the format <username>:<password>@<host>, as shown:

curl https://atatus:@t@tus@example.com/Curl uses “Basic” authentication with the server in each of these techniques.

#14 Testing Protocol Support

You can even use cURL to evaluate protocol support because of the vast number of protocols it supports. The —<sslvversion> and —tlsv<version> flags can be used to see if a site supports a specific version of SSL. If you wish to see if a site supports TLS v1.2, for example, you can use:

curl -v --tlsv1.2 https://www.atatus.com/The request is processed normally, indicating that the site is compatible with TLSv1.2. Let’s see if the site supports SSL v3 now:

curl -v --sslv3 https://www.atatus.com/This command throws a handshake_failed exception because the server doesn’t support this version of SSL.

Please keep in mind that some of these version options may not work based on your system and library version/configuration.

We previously examined how a web server determines which websites to serve to users based on the «Host» header. By adjusting the «Host» header, you may check if your website’s virtual hosting is configured appropriately.

As an example, suppose you have a local server with two websites configured, sample1.com and sample2.com, at 192.168.0.1. Set the Host header and check that the correct contents are served to see if everything is configured correctly:

curl -H 'Host: sample1.com' http://192.168.0.1/

curl -H 'Host: sample2.com' http://192.168.0.1/Unfortunately, this isn’t the case with HTTPS-enabled websites. A single website can be set up to serve several websites, each of which will have its SSL/TLS certificate.

Since SSL/TLS operates at a lower level than HTTP, clients like cURL must notify the server whose website we’re trying to access at the SSL/TLS level for the server to select the appropriate certificate. By default, cURL informs the server of this.

However, if you want to send a request to a specific IP address, such as in the example above, the server may choose the incorrect certificate, causing the SSL/TLS verification to fail. The Host header is only useful on the HTTP level, not on SSL/TLS.

#16 cURL’s —resolve Flag

The —resolve flag can be used to avoid the problem outlined above. The resolve flag will deliver the request to the port and IP of your choice, while appropriately sending the website name over SSL/TLS and HTTP.

Consider the preceding scenario. You can use the following syntax to send HTTPS to the local server 192.168.0.1:

curl https://sample1.com/ --resolve sample1.com:192.168.0.1:443It’s also good for HTTP. If your HTTP server was listening on port 8080, you might use the —resolve flag or manually set the Host header and the port, as seen below:

curl http://192.168.0.1:8080/ -H 'Host: sample1.com:8080'

curl http://sample.com/ --resolve sample1.com:192.168.0.1:8080The two commands shown above are the same.

#17 Resolve Domains to IPv4 and IPv6 Addresses

Sometimes you’ll want to see if a website can be accessed using both IPv4 and IPv6. Using the -4 and -6 flags, you may compel cURL to connect to either the IPv4 or IPv6 version of your site.

Please keep in mind that a website can only be accessed through IPv4 or IPv6 if:

- The website has appropriate DNS entries that connect it to IPv4 and IPv6 addresses.

- On your machine, you have IPv4 and IPv6 connectivity.

You can run the following command to see if you can visit the website icanhazip.com over IPv6:

curl -6 https://icanhazip.com/If the site is accessible through HTTPS, the output should include your IPv6 address. Any client that connects to this website will receive the public IP address of that client. As a result, it shows an IPv4 or IPv6 address, depending on the protocol.

Know the difference between IPv4 and IPv6 — Difference Between IPv4 and IPv6: Why haven’t We Entirely Moved to IPv6?

You can also use the -v option in combination with the -4 and -6 options to acquire extra information.

#18 Disabling cURL’s Certificate Checks

When connecting via HTTPS, cURL examines certificates by default. When you’re trying to make requests to sites that utilize self-signed certificates, or if you need to test a site with a misconfigured certificate, it’s typically handy to disable certificate checking.

Use the -k certificate to disable certificate checking. We’ll put this to the test by sending a request to expired.badssl.com, a website with an expired SSL certificate.

curl -k https://expired.badssl.com/The certificate checks are skipped when using the -k option. As a result, cURL successfully downloads the page and shows the request body. You will, however, receive an error if you did not utilize the -k option.

#19 cURL Configuration Files

You might want to use the same options for all cURL requests at times. Because passing these options by hand isn’t a possibility, cURL lets you provide them in a configuration file.

In Linux/macOS, the default configuration file is placed in ~/.curlrc, whereas in Windows, it is found in %appdata%\_curlrc. You can define any options you require within this file.

Make a request with curl example.com after you’ve created the above file. You’ll notice that these options are now active.

If you want to use a different configuration file than the default, use the -K option to point curl to it. If you have a configuration file named config.txt, for example, you can utilize it with:

curl -K config.txt example.comConclusion

The most common uses of the cURL command have been covered in this article. Of course, this article only scratches the surface; cURL is capable of much more. Visit the Curl Documentation website for more information about curl.

Monitor Your Entire Application with

Atatus

Atatus provides a set of performance measurement tools to monitor and improve the performance of your frontend, backends, logs, and infrastructure applications in real-time. Our platform can capture millions of performance data points from your applications, allowing you to quickly resolve issues and ensure digital customer experiences.

Atatus

can be beneficial to your business, which provides a comprehensive view of your application, including how it works, where performance bottlenecks exist, which users are most impacted, and which errors break your source code for your frontend, backend, and infrastructure.

Try your 14-day free trial of Atatus.

This article is a first in a series of three on the topic of CDN debugging.

Here we will share three tips for collecting useful data, which really is the first thing you want to do when you believe something is wrong with your CDN.

curl -svo /dev/null

Curl (or cURL) is a command line tool widely used for testing and troubleshooting client-server data transfer over HTTP.

The free tool comes preinstalled on Linux and Mac OS X machines and curl for Windows is available too.

When using curl to debug CDN behavior, don’t ever use curl -I.

Using the I flag results in sending a HEAD request and that is often pointless and unintended.

Your users will send GET requests not HEAD requests and the CDN may treat HEAD requests very differently from GET requests.

So remember: don’t use curl -I, ever.

Your curl commands should start with curl -svo /dev/null.

The -svo /dev/null is a series of flags:

-s enables silent mode; don’t show progress meter or error messages.

-v enables verbose output

-o /dev/null sends output to a file, but not really because the /dev/null item does not save anything (note: on Windows, use -o NUL

So, -svo /dev/null gives you a nice and clean display of information, most importantly the request and response headers.

The -H flag can be used to send an arbitrary request header, for example a specific User-Agent string: -H 'User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (iPhone; CPU iPhone OS 6_0 like Mac OS X) AppleWebKit/536.26 (KHTML, like Gecko) Version/6.0 Mobile/10A5376e Safari/8536.25

Below you see an example curl command for fetching the (gzip) compressed version of https://edition.cnn.com/css/2.33.0/global.css.

curl -svo /dev/null --compressed 'https://edition.cnn.com/css/2.33.0/global.css'

Learn more about curl and all the flags by reading the curl manual page.

Don’t test against just one POP

When debugging your CDN, make sure you get don’t fall in the trap of looking into the behavior of just one POP.

It’s important you find out if the problem is POP specific or not and the only way to do that is to test against several/many POPs.

But how do you do that?

Services like Pingdom or Catchpoint have test machines across the globe, and this is great because you can perform tests against POPs in many locations.

However, the visibility you can get using such services is suboptimal.

For example: in France, Level 3 CDN has POPs in Marseille and Paris, but Pingdom only has servers in a datacenter in Strasbourg.

When testing from the Pingdom servers in Strasbourg, you’ll likely hit the same one of two Level 3 POPs every time and consequently know nothing about the other POP.

Ideally, your CDN provides you a way to send a request to a specific POP, so you can run curl tests against each and every POP comfortably from your office computer. Unfortunately, not many CDNs provide this feature.

As far as we know, Edgio and Highwinds (part of StackPath) enable you to debug a specific POP.

Fastly enables sending requests to a specific cache node (e.g. cache-lax1427) which is nice but only useful if you know the cache node that is serving your content. In our opinion, it’s more useful to be able to send a request to ‘the Amsterdam POP’.

To send a request to a specific target endpoint (e.g. a CDNetworks server in Amsterdam), use the -H flag to add a Host header with your domain:

curl -svo /dev/null -H 'Host: cdn.yourdomain.com' 'https://91.194.205.21/path/to/file'

Test from real user networks, not datacenters

Even if you can run curl tests against specific CDN POPs from your office location, or from datacenters across the globe, you’re still somewhat in the dark.

Real users don’t live in your office or in datacenters. They are at home, at work and on the go and connected to last-mile networks.

It’s not uncommon for a CDN’s performance to go bad only for users on one particular last-mile network.

The problem may be a congested network path, suboptimal routing (e.g. users on AS9143 (Ziggo) in NL are routed to New York instead of Amsterdam) or the ISP’s DNS resolvers can’t reach the CDN’s DNS nameservers.

The only way to spot these kind of issues is by testing from devices connected to the last-mile (or: eyeball) networks.