The «enhanced metafile» format was introduced in the 32-bit versions of Windows. It

involves a bunch of new function calls, a couple of new data structures, a new

clipboard format, and a new filename extension of .EMF.

The most important enhancement is that the new metafile format includes

more extensive header information accessible through a function call. This information aids

in helping an application display the metafile image.

Some of the enhanced metafile functions allow you to translate back and forth

between the enhanced metafile (EMF) format and the old metafile format, which is also

called the Windows metafile (WMF) format. Of course, this conversion may not proceed

without hitches because the old metafile format does not support some of the new 32-bit

graphics features, such as paths.

The Basic Procedure

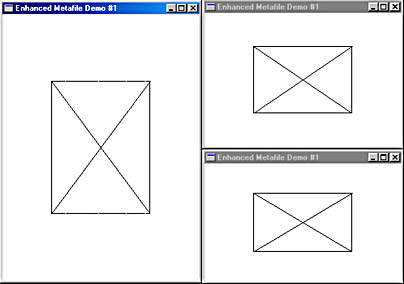

Figure 18-3 shows the EMF1 program, which creates and displays an enhanced

metafile with a fairly minimal amount of distraction.

Figure 18-3. The EMF1 Program.

EMF1.C

/*-------------------------------------

EMF1.C -- Enhanced Metafile Demo #1

(c) Charles Petzold, 1998

-------------------------------------*/

#include <windows.h>

LRESULT CALLBACK WndProc (HWND, UINT, WPARAM, LPARAM) ;

int WINAPI WinMain (HINSTANCE hInstance, HINSTANCE hPrevInstance,

LPSTR lpszCmdLine, int nCmdShow)

{

static TCHAR szAppName[] = TEXT ("EMF1") ;

HWND hwnd ;

MSG msg ;

WNDCLASS wndclass ;

wndclass.style = CS_HREDRAW | CS_VREDRAW ;

wndclass.lpfnWndProc = WndProc ;

wndclass.cbClsExtra = 0 ;

wndclass.cbWndExtra = 0 ;

wndclass.hInstance = hInstance ;

wndclass.hIcon = LoadIcon (NULL, IDI_APPLICATION) ;

wndclass.hCursor = LoadCursor (NULL, IDC_ARROW) ;

wndclass.hbrBackground = GetStockObject (WHITE_BRUSH) ;

wndclass.lpszMenuName = NULL ;

wndclass.lpszClassName = szAppName ;

if (!RegisterClass (&wndclass))

{

MessageBox (NULL, TEXT ("This program requires Windows NT!"),

szAppName, MB_ICONERROR) ;

return 0 ;

}

hwnd = CreateWindow (szAppName, TEXT ("Enhanced Metafile Demo #1"),

WS_OVERLAPPEDWINDOW,

CW_USEDEFAULT, CW_USEDEFAULT,

CW_USEDEFAULT, CW_USEDEFAULT,

NULL, NULL, hInstance, NULL) ;

ShowWindow (hwnd, nCmdShow) ;

UpdateWindow (hwnd) ;

while (GetMessage (&msg, NULL, 0, 0))

{

TranslateMessage (&msg) ;

DispatchMessage (&msg) ;

}

return msg.wParam ;

}

LRESULT CALLBACK WndProc (HWND hwnd, UINT message, WPARAM wParam, LPARAM lParam)

{

static HENHMETAFILE hemf ;

HDC hdc, hdcEMF ;

PAINTSTRUCT ps ;

RECT rect ;

switch (message)

{

case WM_CREATE:

hdcEMF = CreateEnhMetaFile (NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL) ;

Rectangle (hdcEMF, 100, 100, 200, 200) ;

MoveToEx (hdcEMF, 100, 100, NULL) ;

LineTo (hdcEMF, 200, 200) ;

MoveToEx (hdcEMF, 200, 100, NULL) ;

LineTo (hdcEMF, 100, 200) ;

hemf = CloseEnhMetaFile (hdcEMF) ;

return 0 ;

case WM_PAINT:

hdc = BeginPaint (hwnd, &ps) ;

GetClientRect (hwnd, &rect) ;

rect.left = rect.right / 4 ;

rect.right = 3 * rect.right / 4 ;

rect.top = rect.bottom / 4 ;

rect.bottom = 3 * rect.bottom / 4 ;

PlayEnhMetaFile (hdc, hemf, &rect) ;

EndPaint (hwnd, &ps) ;

return 0 ;

case WM_DESTROY:

DeleteEnhMetaFile (hemf) ;

PostQuitMessage (0) ;

return 0 ;

}

return DefWindowProc (hwnd, message, wParam, lParam) ;

}

During WM_CREATE message processing in EMF1’s window procedure, the

program creates the enhanced metafile, beginning with a call to

CreateEnhMetaFile. This function requires four arguments, but you can set all of them to NULL. I’ll discuss how to use

these arguments with non-NULL values shortly.

Like CreateMetaFile, the

CreateEnhMetaFile function returns a special device

context handle. The program uses this handle to draw a rectangle and two lines connecting

the opposite corners of the rectangle. These function calls and their arguments are

converted to a binary form and stored in the metafile.

Finally, a call to CloseEnhMetaFile wraps up the creation of the enhanced

metafile and returns a handle to it. This is stored in a static variable of type HENHMETAFILE.

During the WM_PAINT message, EMF1 obtains the dimensions of the program’s

client window in a RECT structure. The four fields of the structure are adjusted so that

the rectangle is half the width and height of the client window and centered within it.

EMF1 then calls PlayEnhMetaFile. The first argument is a handle to the window’s device

context, the second argument is the handle to the enhanced metafile, and the third

argument is a pointer to the RECT structure.

What happens here is that during creation of the metafile, GDI figures out the

entire dimensions of the metafile image. In this case, the image is 100 units high and wide.

When displaying the metafile, GDI stretches the image to fit the rectangle specified in

the PlayEnhMetaFile function. Three instances of EMF1 running under Windows are

shown in Figure 18-4.

Figure 18-4. The EMF1 Display.

Finally, during the WM_DESTROY message, EMF1 deletes the metafile by

calling DeleteEnhMetaFile.

Let’s take note of a few things we can learn from the EMF1 program.

First, in this particular program, the coordinates used in the rectangle and

line-drawing functions when creating the enhanced metafile don’t really mean all that much. You

can double them all or subtract a constant from them all, and the results will be the same.

All that matters is that the coordinates have a relationship among themselves in defining an image.

Second, the image is stretched to fit the rectangle passed to the

PlayEnhMetaFile function. Thus, as Figure 18-4 clearly shows, the image can be distorted. The

metafile coordinates imply that the image is square, but that’s not what we get in the general

case. And sometimes, that’s exactly what you want. For embedding images in a word

processing text, you may want the user to specify a rectangle for the image and be assured

that the entire image fits exactly within the rectangle without any wasted space. Let the

user worry about the correct aspect ratio by adjusting the rectangle appropriately.

However, there are times when something else is appropriate. You may want

to maintain the aspect ratio of the original image because it may be vitally important to

rendering the visual information. For example, a police sketch of a crime suspect

shouldn’t be fatter or squatter than it was originally drawn. Or, you may want to preserve the

metrical size of the original image. It may be important that the image is two inches high

and shouldn’t normally be reproduced otherwise.

Notice also that the lines drawn in the metafile don’t seem to exactly meet the

corners of the rectangle. This is the result of a problem in the way that Windows stores

rectangle coordinates in the metafile. We’ll work on a fix to this problem later in this chapter.

Looking Inside

You can get a good feel for how metafiles work by looking at the contents of the

metafile. This is easiest if you have a disk-based metafile to look at, so the EMF2 program

shown in Figure 18-5 creates one for you.

Figure 18-5. The EMF2 Program.

EMF2.C

/*-------------------------------------

EMF2.C -- Enhanced Metafile Demo #2

(c) Charles Petzold, 1998

-------------------------------------*/

#include <windows.h>

LRESULT CALLBACK WndProc (HWND, UINT, WPARAM, LPARAM) ;

int WINAPI WinMain (HINSTANCE hInstance, HINSTANCE hPrevInstance,

LPSTR lpszCmdLine, int nCmdShow)

{

static TCHAR szAppName[] = TEXT ("EMF2") ;

HWND hwnd ;

MSG msg ;

WNDCLASS wndclass ;

wndclass.style = CS_HREDRAW | CS_VREDRAW ;

wndclass.lpfnWndProc = WndProc ;

wndclass.cbClsExtra = 0 ;

wndclass.cbWndExtra = 0 ;

wndclass.hInstance = hInstance ;

wndclass.hIcon = LoadIcon (NULL, IDI_APPLICATION) ;

wndclass.hCursor = LoadCursor (NULL, IDC_ARROW) ;

wndclass.hbrBackground = GetStockObject (WHITE_BRUSH) ;

wndclass.lpszMenuName = NULL ;

wndclass.lpszClassName = szAppName ;

if (!RegisterClass (&wndclass))

{

MessageBox (NULL, TEXT ("This program requires Windows NT!"),

szAppName, MB_ICONERROR) ;

return 0 ;

}

hwnd = CreateWindow (szAppName, TEXT ("Enhanced Metafile Demo #2"),

WS_OVERLAPPEDWINDOW,

CW_USEDEFAULT, CW_USEDEFAULT,

CW_USEDEFAULT, CW_USEDEFAULT,

NULL, NULL, hInstance, NULL) ;

ShowWindow (hwnd, nCmdShow) ;

UpdateWindow (hwnd) ;

while (GetMessage (&msg, NULL, 0, 0))

{

TranslateMessage (&msg) ;

DispatchMessage (&msg) ;

}

return msg.wParam ;

}

LRESULT CALLBACK WndProc (HWND hwnd, UINT message, WPARAM wParam, LPARAM lParam)

{

HDC hdc, hdcEMF ;

HENHMETAFILE hemf ;

PAINTSTRUCT ps ;

RECT rect ;

switch (message)

{

case WM_CREATE:

hdcEMF = CreateEnhMetaFile (NULL, TEXT ("emf2.emf"), NULL,

TEXT ("EMF2\0EMF Demo #2\0")) ;

if (!hdcEMF)

return 0 ;

if (GetVersion () & 0x80000000) //Windows 98

Rectangle (hdcEMF, 100, 100, 201, 201) ;

else //Windows NT

Rectangle (hdcEMF, 101, 101, 202, 202) ;

MoveToEx (hdcEMF, 100, 100, NULL) ;

LineTo (hdcEMF, 200, 200) ;

MoveToEx (hdcEMF, 200, 100, NULL) ;

LineTo (hdcEMF, 100, 200) ;

hemf = CloseEnhMetaFile (hdcEMF) ;

DeleteEnhMetaFile (hemf) ;

return 0 ;

case WM_PAINT:

hdc = BeginPaint (hwnd, &ps) ;

GetClientRect (hwnd, &rect) ;

rect.left = rect.right / 4 ;

rect.right = 3 * rect.right / 4 ;

rect.top = rect.bottom / 4 ;

rect.bottom = 3 * rect.bottom / 4 ;

if (hemf = GetEnhMetaFile (TEXT ("emf2.emf")))

{

PlayEnhMetaFile (hdc, hemf, &rect) ;

DeleteEnhMetaFile (hemf) ;

}

EndPaint (hwnd, &ps) ;

return 0 ;

case WM_DESTROY:

PostQuitMessage (0) ;

return 0 ;

}

return DefWindowProc (hwnd, message, wParam, lParam) ;

}

In EMF1, all the arguments to the

CreateEnhMetaFile function were set to NULL.

In EMF2, the first argument is also set to NULL. This argument can be a device context

handle. GDI uses this argument to insert metrical information in the metafile header, as we’ll

see shortly. If the argument is set to NULL, GDI assumes that this metrical information is

based on the video device context.

The second argument to CreateEnhMetaFile is a filename. If you set this argument to NULL (as EMF1 does but EMF2 does not), then the function creates a memory metafile. EMF2 creates a disk-based metafile with the name EMF2.EMF.

The third argument to the function is an address of a RECT structure that

indicates the total dimensions of the metafile in 0.01 mm units. This piece of vital information (one of the deficiencies of the earlier Windows metafile format) goes into the metafile header, as we’ll soon see. If you set this argument to NULL, GDI will figure out the dimensions for you. I like the idea of operating systems doing things for me, so I’ve set the

argument to NULL. If performance is critical in your application, you might want to use this argument to avoid some extraneous work on GDI’s part.

Finally, the last argument is a text string describing the metafile. This text string is specified in two pieces: the first piece is the name of the application (not necessarily the program filename) followed by a NULL character, and the second piece describes the visual image and is followed by two NULL characters. For example, using the C notation of `\0′ for a NULL character, the description string could be «LoonyCad V6.4\0Flying Frogs\0\0». Because C normally puts a NULL character at the end of quoted strings, you need only one `\0′ at the end, as EMF2 demonstrates.

After creating the metafile, EMF2 proceeds like EMF1 and makes a few GDI

function calls by using the device context handle returned from the

CreateEnhMetaFile function. The program then calls

CloseEnhMetaFile to destroy the device context handle and

obtain a handle to the completed metafile.

Then, still during WM_CREATE processing, EMF2 does something EMF1 does not: right after obtaining the metafile handle, the program calls

DeleteEnhMetaFile. That gets rid of all memory resources required to maintain the metafile. However, the disk-based

metafile stays behind. (If you ever want to get rid of that file, use a normal file-deletion

function such as DeleteFile.) Notice that the metafile handle is not stored as a static variable as

in EMF1, which implies that it is not required to be saved between messages.

Now, to use that metafile, EMF2 needs to access the disk file. It does this during the WM_PAINT message by calling

GetEnhMetaFile. The single argument to the

function is the metafile filename, and the function returns a handle to the metafile. EMF2 passes this handle to the PlayEnhMetaFile function, just as in EMF1. The metafile image is

displayed in the rectangle described by the last argument to the function. But unlike EMF1, EMF2 deletes the metafile before concluding WM_PAINT processing. During any following WM_PAINT messages, EMF2 gets the metafile again, plays it, and deletes it.

Keep in mind that deleting the metafile involves deleting only the memory resources required for maintaining the metafile. The disk-based metafile stays behind, even after the program has concluded execution.

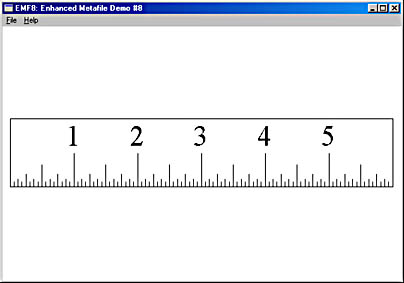

Because EMF2 leaves behind a disk-based metafile, you can take a look at it. Figure 18-6 shows a simple hexadecimal dump of the EMF2.EMF file that the program

creates.

0000 01 00 00 00 88 00 00 00 64 00 00 00 64 00 00 00 ........d...d... 0010 C8 00 00 00 C8 00 00 00 35 0C 00 00 35 0C 00 00 ........5...5... 0020 6A 18 00 00 6A 18 00 00 20 45 4D 46 00 00 01 00 j...j... EMF.... 0030 F4 00 00 00 07 00 00 00 01 00 00 00 12 00 00 00 ................ 0040 64 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 04 00 00 00 03 00 00 d............... 0050 40 01 00 00 F0 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 @............... 0060 00 00 00 00 45 00 4D 00 46 00 32 00 00 00 45 00 ....E.M.F.2...E. 0070 4D 00 46 00 20 00 44 00 65 00 6D 00 6F 00 20 00 M.F. .D.e.m.o. . 0080 23 00 32 00 00 00 00 00 2B 00 00 00 18 00 00 00 #.2.....+....... 0090 63 00 00 00 63 00 00 00 C6 00 00 00 C6 00 00 00 c...c........... 00A0 1B 00 00 00 10 00 00 00 64 00 00 00 64 00 00 00 ........d...d... 00B0 36 00 00 00 10 00 00 00 C8 00 00 00 C8 00 00 00 6............... 00C0 1B 00 00 00 10 00 00 00 C8 00 00 00 64 00 00 00 ............d... 00D0 36 00 00 00 10 00 00 00 64 00 00 00 C8 00 00 00 6.......d....... 00E0 0E 00 00 00 14 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 10 00 00 00 ................ 00F0 14 00 00 00 ....

Figure 18-6. A hexadecimal dump of EMF2.EMF.

I should note that Figure 18-6 shows the metafile created by EMF2 under

Microsoft Windows NT 4 running with a video display resolution of 1024 by 768. The

metafile created by the same program running under Windows 98 will be 12 bytes shorter, as

I’ll discuss shortly. Also, the video display resolution will affect some of the information

in the metafile header.

Looking at the enhanced metafile format allows us to more deeply understand

the workings of metafiles. The enhanced metafile consists of variable-length records.

The general format of these records is described by the ENHMETARECORD structure,

defined in the WINGDI.H header file like so:

typedef struct tagENHMETARECORD

{

DWORD iType ; // record type

DWORD nSize ; // record size

DWORD dParm [1] ; // parameters

}

ENHMETARECORD ;

Of course, that array of one element really indicates a variable number of array

elements. The number of parameters depends on the record type. The

iType field can be one of nearly 100 constants beginning with the prefix EMR_ defined in the WINGDI.H file. The

nSize field is the size of the total record, including the

iType and nSize fields, and one or

more dParm fields.

With this knowledge, let’s look at Figure 18-6. The first field has a type of

0x00000001 and a size of 0x00000088, so it occupies the first 136 bytes of the file. A record type of

1 is the constant EMR_HEADER. I want to leave the discussion of the header for later, so

for now let’s just skip to offset 0x0088, at the end of this first record.

The next five records correspond to the five GDI calls that EMF2 makes after

creating the metafile. The record at offset 0x0088 has a type code of 0x0000002B, which

is EMR_RECTANGLE, obviously the metafile record for the

Rectangle call. It has a length of 0x00000018 (24 in decimal) bytes to accommodate four 32-bit arguments. The

Rectangle function actually has five arguments, of course, but the first—the handle to the

device context—is not stored in the metafile because it would have no real meaning. There

are two arguments of 0x00000063 (or 99) and two arguments of 0x000000C6 (or 198),

even though the function call in EMF2 specifies that the

Rectangle corners are (100, 100) and (200, 200). The metafile created by the EMF2 program under Windows 98 will show

the first two arguments as 0x00000064 (or 100) and the next two as 0x000000C7 (or

199). Obviously, Windows is making an adjustment to the

Rectangle arguments before they are stored in the metafile but not doing it consistently. This is why the lines do not match

the corners of the rectangle.

Next, we have four 16-byte records corresponding to the two

MoveToEx (0x0000001B or EMR_MOVETOEX) and

LineTo (0x00000036 or EMR_LINETO) calls. The arguments

in the metafile are the same as those passed to the functions.

The metafile ends with a type code of 0x0000000E or EMR_EOF («end of file»),

a 20-byte record.

The enhanced metafile always begins with a header record. This corresponds to

a structure of type ENHMETAHEADER, which is defined like so:

typedef struct tagENHMETAHEADER

{

DWORD iType ; // EMR_HEADER = 1

DWORD nSize ; // structure size

RECTL rclBounds ; // bounding rectangle in pixels

RECTL rclFrame ; // size of image in 0.01 millimeters

DWORD dSignature ; // ENHMETA_SIGNATURE = " EMF"

DWORD nVersion ; // 0x00010000

DWORD nBytes ; // file size in bytes

DWORD nRecords ; // total number of records

WORD nHandles ; // number of handles in handle table

WORD sReserved ;

DWORD nDescription ; // character length of description string

DWORD offDescription ; // offset of description string in file

DWORD nPalEntries ; // number of entries in palette

SIZEL szlDevice ; // device resolution in pixels

SIZEL szlMillimeters ; // device resolution in millimeters

DWORD cbPixelFormat ; // size of pixel format

DWORD offPixelFormat ; // offset of pixel format

DWORD bOpenGL ; // FALSE if no OpenGL records

}

ENHMETAHEADER ;

The existence of this header record is probably the single greatest improvement

of the enhanced metafile format over the old Windows metafile. You do not need to use

the file I/O function on the disk-based metafile to obtain this header information. If you

have a handle to the metafile, you can use the

GetEnhMetaFileHeader function:

GetEnhMetaFileHeader (hemf, cbSize, &emh) ;

The first argument is the metafile handle, the last is a pointer to an

ENHMETAHEADER structure, and the second is the size of this structure. You can use the similar

GetEnhMetaFileDescription function to obtain the description string.

As defined above, the ENHMETAHEADER structure is 100 bytes in length, but in

the EMF2.EMF metafile the size of the record includes the description string, so the size is

0x88 or 136 bytes. The header stored in a Windows 98 metafile does not include the last

three fields of the ENHMETAHEADER structure, which accounts for the 12-byte difference in size.

The rclBounds field is a RECT structure that indicates the size of the image in

pixels. Translating from hexadecimal, we see that the image is bounded by the points (100,

100) on the upper left and (200, 200) on the lower right, exactly what we expect.

The rclFrame field is another rectangle structure that provides the same

information but in units of 0.01 millimeters. In this case, the file shows a bounding rectangle of

(0x0C35, 0x0C35) by (0x186A, 0x186A) or, in decimal, (3125, 3125) by (6250, 6250). Where does

this information come from? We’ll see shortly.

The dSignature field is always the value ENHMETA_SIGNATURE, or 0x464D4520.

That seems like a strange number, but if you reverse the byte ordering (in accordance with

how multibyte values are stored in memory with Intel processors) and convert to ASCII,

it’s simply the string » EMF». The

dVersion field is always 0x00010000.

This is followed by the nBytes field, which in this case is 0x000000F4, the total

byte size of the metafile. The nRecords field (in this case, 0x00000007) indicates the number

or records—the header record, the five GDI function calls, and the end-of-file record.

Next we have two 16-bit fields. The

nHandles field is 0x0001. Normally this

field would indicate the number of nondefault handles to graphics objects (such as pens,

brushes, and fonts) used in the metafile. We haven’t done that, so you might expect the field to

be zero, but GDI reserves the first one for itself. We’ll see how handles are stored in

metafiles shortly.

The next two fields indicate the length of the description string in characters and

its offset within the file, in this case 0x00000012 (18 in decimal) and 0x00000064. If the

metafile did not have a description string, both these fields would be zero.

The nPalEntries field indicates the number of entries in the metafile’s palette

table, in this case none.

The header record continues with two SIZEL structures, which contain two

32-bit fields, cx and cy. The

szlDevice field (at offset 0x0040 in the metafile) indicates the size

of the output device in pixels, and the

szlMillimeters field (at offset 0x0050) is the size of

the output device in millimeters. In the documentation of the enhanced metafile, this

output device is called the «reference device.» It is based on the device context indicated by

the handle passed as the first argument to the

CreateEnhMetaFile call. If the argument is

set to NULL, GDI uses the video display. When EMF2 created the metafile shown above,

I happened to be running Windows NT in a 1024 by 768 video mode, so that’s what

GDI used as the reference device.

GDI obtains this information from

GetDeviceCaps. The szlDevice field in

EMF2.EMF is 0x0400 by 0x0300 (that is, 1024 by 768), which is obtained from

GetDeviceCaps using the HORZRES and VERTRES arguments. The

szlMillimeters field is 0x140 by 0xF0 or

320 by 240, obtained from GetDeviceCaps using the HORZSIZE and VERTSIZE arguments.

A simple division reveals that the pixels are 0.3125 millimeters high and wide,

which is how GDI figures out the dimensions of the

rclFrame rectangle described above.

The ENHMETAHEADER structure is followed in the metafile by the

description string, which was the last argument to

CreateEnhMetaFile. In this example, this is

the string «EMF2» followed by a NULL character and «EMF Demo #2» followed by two

NULL characters. That’s a total of 18 characters, or 36 bytes because it’s stored in Unicode.

The string is always stored in Unicode regardless of whether the program creating the

metafile is running under Windows NT or Windows 98.

Metafiles and GDI Objects

We’ve now seen how GDI drawing commands are stored in metafiles. Now let’s

examine how GDI objects are stored. The EMF3 program shown in Figure 18-7 is similar to the EMF2 program shown earlier, except that it creates a nondefault pen and

brush for drawing the rectangle and lines. I’ve also provided a little fix for the problem

with the coordinates to Rectangle. EMF3 uses

GetVersion to determine if it’s running

under Windows 98 or Windows NT, and to adjust the arguments appropriately.

Figure 18-7. The EMF3 program.

EMF3.C

/*-------------------------------------

EMF3.C -- Enhanced Metafile Demo #3

(c) Charles Petzold, 1998

-------------------------------------*/

#include <windows.h>

LRESULT CALLBACK WndProc (HWND, UINT, WPARAM, LPARAM) ;

int WINAPI WinMain (HINSTANCE hInstance, HINSTANCE hPrevInstance,

PSTR szCmdLine, int iCmdShow)

{

static TCHAR szAppName[] = TEXT ("EMF3") ;

HWND hwnd ;

MSG msg ;

WNDCLASS wndclass ;

wndclass.style = CS_HREDRAW | CS_VREDRAW ;

wndclass.lpfnWndProc = WndProc ;

wndclass.cbClsExtra = 0 ;

wndclass.cbWndExtra = 0 ;

wndclass.hInstance = hInstance ;

wndclass.hIcon = LoadIcon (NULL, IDI_APPLICATION) ;

wndclass.hCursor = LoadCursor (NULL, IDC_ARROW) ;

wndclass.hbrBackground = GetStockObject (WHITE_BRUSH) ;

wndclass.lpszMenuName = NULL ;

wndclass.lpszClassName = szAppName ;

if (!RegisterClass (&wndclass))

{

MessageBox (NULL, TEXT ("This program requires Windows NT!"),

szAppName, MB_ICONERROR) ;

return 0 ;

}

hwnd = CreateWindow (szAppName, TEXT ("Enhanced Metafile Demo #3"),

WS_OVERLAPPEDWINDOW,

CW_USEDEFAULT, CW_USEDEFAULT,

CW_USEDEFAULT, CW_USEDEFAULT,

NULL, NULL, hInstance, NULL) ;

ShowWindow (hwnd, iCmdShow) ;

UpdateWindow (hwnd) ;

while (GetMessage (&msg, NULL, 0, 0))

{

TranslateMessage (&msg) ;

DispatchMessage (&msg) ;

}

return msg.wParam ;

}

LRESULT CALLBACK WndProc (HWND hwnd, UINT message, WPARAM wParam, LPARAM lParam)

{

LOGBRUSH lb ;

HDC hdc, hdcEMF ;

HENHMETAFILE hemf ;

PAINTSTRUCT ps ;

RECT rect ;

switch (message)

{

case WM_CREATE:

hdcEMF = CreateEnhMetaFile (NULL, TEXT ("emf3.emf"), NULL,

TEXT ("EMF3\0EMF Demo #3\0")) ;

SelectObject (hdcEMF, CreateSolidBrush (RGB (0, 0, 255))) ;

lb.lbStyle = BS_SOLID ;

lb.lbColor = RGB (255, 0, 0) ;

lb.lbHatch = 0 ;

SelectObject (hdcEMF,

ExtCreatePen (PS_SOLID | PS_GEOMETRIC, 5, &lb, 0, NULL)) ;

Rectangle (hdcEMF, 100, 100, 200, 200) ;

MoveToEx (hdcEMF, 100, 100, NULL) ;

LineTo (hdcEMF, 200, 200) ;

MoveToEx (hdcEMF, 200, 100, NULL) ;

LineTo (hdcEMF, 100, 200) ;

DeleteObject (SelectObject (hdcEMF, GetStockObject (BLACK_PEN))) ;

DeleteObject (SelectObject (hdcEMF, GetStockObject (WHITE_BRUSH))) ;

hemf = CloseEnhMetaFile (hdcEMF) ;

DeleteEnhMetaFile (hemf) ;

return 0 ;

case WM_PAINT:

hdc = BeginPaint (hwnd, &ps) ;

GetClientRect (hwnd, &rect) ;

rect.left = rect.right / 4 ;

rect.right = 3 * rect.right / 4 ;

rect.top = rect.bottom / 4 ;

rect.bottom = 3 * rect.bottom / 4 ;

hemf = GetEnhMetaFile (TEXT ("emf3.emf")) ;

PlayEnhMetaFile (hdc, hemf, &rect) ;

DeleteEnhMetaFile (hemf) ;

EndPaint (hwnd, &ps) ;

return 0 ;

case WM_DESTROY:

PostQuitMessage (0) ;

return 0 ;

}

return DefWindowProc (hwnd, message, wParam, lParam) ;

}

As we’ve seen, when you call GDI functions using the device context handle returned from CreateEnhMetaFile, the function calls are stored in the metafile rather than being rendered on the screen or printer. However, some GDI functions do not refer to a particular device context at all. One important category of these GDI functions are those that create graphics objects, including pens and brushes. Although the definitions of logical pens and brushes are stored in memory maintained by GDI, these abstract definitions are not associated with any particular device context when they’re created.

EMF3 calls both the CreateSolidBrush and

ExtCreatePen functions. Because these functions do not require a device context handle, this implies that GDI will not store these

calls in the metafile. This implication is true. When called by themselves, GDI functions simply create the graphics drawing object without affecting the metafile at all.

However, when a program calls SelectObject to select a GDI object into the metafile device context, GDI encodes both an object-creation function (essentially derived from the internal GDI data used to stored the object) and a SelectObject call in the metafile. To see how this works, let’s take a look at the hexadecimal dump of EMF3.EMF,

shown in Figure 18-8.

0000 01 00 00 00 88 00 00 00 60 00 00 00 60 00 00 00 ........`...`... 0010 CC 00 00 00 CC 00 00 00 B8 0B 00 00 B8 0B 00 00 ................ 0020 E7 18 00 00 E7 18 00 00 20 45 4D 46 00 00 01 00 ........ EMF.... 0030 88 01 00 00 0F 00 00 00 03 00 00 00 12 00 00 00 ................ 0040 64 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 04 00 00 00 03 00 00 d............... 0050 40 01 00 00 F0 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 @............... 0060 00 00 00 00 45 00 4D 00 46 00 33 00 00 00 45 00 ....E.M.F.3...E. 0070 4D 00 46 00 20 00 44 00 65 00 6D 00 6F 00 20 00 M.F. .D.e.m.o. . 0080 23 00 33 00 00 00 00 00 27 00 00 00 18 00 00 00 #.3.....'....... 0090 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 FF 00 00 00 00 00 ................ 00A0 25 00 00 00 0C 00 00 00 01 00 00 00 5F 00 00 00 %..........._... 00B0 34 00 00 00 02 00 00 00 34 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 4.......4....... 00C0 34 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 01 00 05 00 00 00 4............... 00D0 00 00 00 00 FF 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................ 00E0 25 00 00 00 0C 00 00 00 02 00 00 00 2B 00 00 00 %...........+... 00F0 18 00 00 00 63 00 00 00 63 00 00 00 C6 00 00 00 ....c...c....... 0100 C6 00 00 00 1B 00 00 00 10 00 00 00 64 00 00 00 ............d... 0110 64 00 00 00 36 00 00 00 10 00 00 00 C8 00 00 00 d...6........... 0120 C8 00 00 00 1B 00 00 00 10 00 00 00 C8 00 00 00 ................ 0130 64 00 00 00 36 00 00 00 10 00 00 00 64 00 00 00 d...6.......d... 0140 C8 00 00 00 25 00 00 00 0C 00 00 00 07 00 00 80 ....%........... 0150 28 00 00 00 0C 00 00 00 02 00 00 00 25 00 00 00 (...........%... 0160 0C 00 00 00 00 00 00 80 28 00 00 00 0C 00 00 00 ........(....... 0170 01 00 00 00 0E 00 00 00 14 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................ 0180 10 00 00 00 14 00 00 00 ........

Figure 18-8. A hexadecimal dump of EMF3.EMF.

You may want to compare this metafile with EMF2.EMF shown earlier. The first difference you’ll see in the header section of EMF3.EMF is the

rclBounds field. EMF2.EMF indicated that the image was bound between coordinates (0x64,0x64) and (0xC8, 0xC8). In EMF3.EMF it’s (0x60,0x60) and (0xCC,0xCC). This reflects using a wider pen. The

rclFrame field (indicating the size of the image in units of 0.01 millimeters) is also affected.

While the nBytes field (located at offset 0x0030) of EMF2.EMF indicated that

the metafile was 0xFA bytes, EMF3.EMF is 0x0188 bytes. The EMF2.EMF metafile contained

7 records (the header, 5 GDI function calls, and the end-of-file record), but EMF3.EMF

has 15. As we’ll see, the extra 8 records are for 2 object-creation functions, 4 calls to

SelectObject, and 2 DeleteObject calls.

The nHandles field (at offset 0x0038 in the file) indicates the number of handles

to GDI objects. This is always one more than the number of nondefault objects used by

the metafile. (The way that the Platform SDK documentation indicates this is «Index zero

in this table is reserved.») The field is 1 in EMF2.EMF and 3 in EMF3.EMF, indicating the

pen and the brush.

Let’s skip to offset 0x0088 in the file, which is the second record (the first

after the header). The record type is 0x27, which corresponds to the constant EMR_CREATEBRUSHINDIRECT. This is the metafile record for the

CreateBrushIndirect function, which requires a pointer to a LOGBRUSH structure. The size of the record is

0x18 (or 24) bytes.

Each nonstock GDI object that is selected into the metafile device context is

assigned a number beginning with 1. This is indicated by the next 4-byte word in this record, at

offset 0x0090 in the metafile. The next three 4-byte fields in this record correspond to the

three fields of the LOGBRUSH structure, 0x00000000 (the

lbStyle field of BS_SOLID), 0x00FF0000 (the

lbColor field), and 0x00000000 (the

lbHatch field).

At offset 0x00A0 in EMF3.EMF is the next record, which has a record type of

0x25, or EMR_SELECTOBJECT, the metafile record for the

SelectObject call. The record is 0x0C (or 12) bytes long, and the next field is the number 0x01, indicating that it’s selecting

the first GDI object, which is the logical brush.

At offset 0x00AC in EMF3.EMF is the next record, which has a record type of

0x5F, or EMR_EXTCREATEPEN. The record is 0x34 (or 52) bytes. The next 4-byte field is

0x02, which means this is the second nonstock GDI object used in the metafile.

I won’t pretend that I know why the next four fields of the

EMR_EXTCREATEPEN record repeat the record size twice, interspersed with 0 fields, but there they are: 0x34,

0x00, 0x34, and 0x00. The next field is 0x00010000, which is the pen style of

PS_SOLID (0x00000000) combined with PS_GEOMETRIC (0x00010000). The width of five units is

next, followed by the three fields of the logical brush structure used in the

ExtCreatePen function, followed by a field of 0.

If you create a custom extended pen style, the EMR_EXTCREATEPEN record will

be longer than 52 bytes, and this will be reflected not only in the second field of the

record, but in the two repeated size fields. Following the three fields that describe the

LOGBRUSH structure, the next field will not be 0 (as it is in EMF3.EMF) but will indicate the

number of dashes and spaces. This is followed by that many fields for the dash and space lengths.

The next 12-byte field in EMF3.EMF is another

SelectObject call indicating the second object—the pen. The next five records are the same as EMF2.EMF—a record type

of 0x2B (EMR_RECTANGLE), and two sets of records of 0x1B (EMR_MOVETOEX) and

0x36 (EMR_LINETO).

These drawing functions are followed by two sets of 12-byte records of 0x25 (EMR_SELECTOBJECT) and 0x28 (EMR_DELETEOBJECT). The select-object records have

arguments of 0x80000007 and 0x80000000. When the high bit is set, it indicates a stock

object, in this case 0x07 (corresponding to BLACK_PEN) and 0x00 (WHITE_BRUSH).

The DeleteObject calls have arguments of 2 and 1, for the two nondefault objects

used in the metafile. Although the

DeleteObject function does not require a device context

handle as the first argument, GDI apparently keeps track of objects used in the metafile that

are deleted by the program.

Finally, the metafile concludes with a 0x0E record, which is EMF_EOF («end of file»).

To sum up, whenever a nondefault GDI object is first selected into a metafile

device context, GDI encodes both a record indicating the object-creation function (in this

case, EMR_CREATEBRUSHINDIRECT and EMR_EXTCREATEPEN). Each object will have a

unique number beginning with 1, indicated by the third field of the record. This record will

be followed by an EMR_SELECTOBJECT record referencing that number. On subsequent

times an object is selected into the metafile device context (without being deleted in the

interim), only an EMR_SELECTOBJECT record is required.

Metafiles and Bitmaps

Let’s try something a little more complex now, in particular drawing a bitmap in a

metafile device context. This is shown in EMF4, in Figure 18-9.

Figure 18-9. The EMF4 program.

EMF4.C

/*-------------------------------------

EMF4.C -- Enhanced Metafile Demo #4

(c) Charles Petzold, 1998

-------------------------------------*/

#define OEMRESOURCE

#include <windows.h>

LRESULT CALLBACK WndProc (HWND, UINT, WPARAM, LPARAM) ;

int WINAPI WinMain (HINSTANCE hInstance, HINSTANCE hPrevInstance,

PSTR szCmdLine, int iCmdShow)

{

static TCHAR szAppName[] = TEXT ("EMF4") ;

HWND hwnd ;

MSG msg ;

WNDCLASS wndclass ;

wndclass.style = CS_HREDRAW | CS_VREDRAW ;

wndclass.lpfnWndProc = WndProc ;

wndclass.cbClsExtra = 0 ;

wndclass.cbWndExtra = 0 ;

wndclass.hInstance = hInstance ;

wndclass.hIcon = LoadIcon (NULL, IDI_APPLICATION) ;

wndclass.hCursor = LoadCursor (NULL, IDC_ARROW) ;

wndclass.hbrBackground = GetStockObject (WHITE_BRUSH) ;

wndclass.lpszMenuName = NULL ;

wndclass.lpszClassName = szAppName ;

if (!RegisterClass (&wndclass))

{

MessageBox (NULL, TEXT ("This program requires Windows NT!"),

szAppName, MB_ICONERROR) ;

return 0 ;

}

hwnd = CreateWindow (szAppName, TEXT ("Enhanced Metafile Demo #4"),

WS_OVERLAPPEDWINDOW,

CW_USEDEFAULT, CW_USEDEFAULT,

CW_USEDEFAULT, CW_USEDEFAULT,

NULL, NULL, hInstance, NULL) ;

ShowWindow (hwnd, iCmdShow) ;

UpdateWindow (hwnd) ;

while (GetMessage (&msg, NULL, 0, 0))

{

TranslateMessage (&msg) ;

DispatchMessage (&msg) ;

}

return msg.wParam ;

}

LRESULT CALLBACK WndProc (HWND hwnd, UINT message, WPARAM wParam, LPARAM lParam)

{

BITMAP bm ;

HBITMAP hbm ;

HDC hdc, hdcEMF, hdcMem ;

HENHMETAFILE hemf ;

PAINTSTRUCT ps ;

RECT rect ;

switch (message)

{

case WM_CREATE:

hdcEMF = CreateEnhMetaFile (NULL, TEXT ("emf4.emf"), NULL,

TEXT ("EMF4\0EMF Demo #4\0")) ;

hbm = LoadBitmap (NULL, MAKEINTRESOURCE (OBM_CLOSE)) ;

GetObject (hbm, sizeof (BITMAP), &bm) ;

hdcMem = CreateCompatibleDC (hdcEMF) ;

SelectObject (hdcMem, hbm) ;

StretchBlt (hdcEMF, 100, 100, 100, 100,

hdcMem, 0, 0, bm.bmWidth, bm.bmHeight, SRCCOPY) ;

DeleteDC (hdcMem) ;

DeleteObject (hbm) ;

hemf = CloseEnhMetaFile (hdcEMF) ;

DeleteEnhMetaFile (hemf) ;

return 0 ;

case WM_PAINT:

hdc = BeginPaint (hwnd, &ps) ;

GetClientRect (hwnd, &rect) ;

rect.left = rect.right / 4 ;

rect.right = 3 * rect.right / 4 ;

rect.top = rect.bottom / 4 ;

rect.bottom = 3 * rect.bottom / 4 ;

hemf = GetEnhMetaFile (TEXT ("emf4.emf")) ;

PlayEnhMetaFile (hdc, hemf, &rect) ;

DeleteEnhMetaFile (hemf) ;

EndPaint (hwnd, &ps) ;

return 0 ;

case WM_DESTROY:

PostQuitMessage (0) ;

return 0 ;

}

return DefWindowProc (hwnd, message, wParam, lParam) ;

}

For convenience, EMF4 loads a system bitmap indicated by the constant

OEM_CLOSE. The customary way of displaying a bitmap in a device context is to create a memory

device context compatible with the destination device context (in this case, that’s the

metafile device context) by calling

CreateCompatibleDC. Then you select the bitmap into

that memory device context by using

SelectObject and call BitBlt or

StretchBlt from the memory source device context to the destination device context. When you’re finished, you

delete both the memory device context and the bitmap.

You’ll note that EMF4 also calls GetObject to determine the size of the bitmap.

This is necessary for the SelectObject call.

At first, the storage of this code in a metafile seems like a real challenge for GDI.

No function leading up the StretchBlt call involves the metafile device context at all. So

let’s see how it’s done by taking a look at EMF4.EMF, which is partially shown in Figure 18-10.

0000 01 00 00 00 88 00 00 00 64 00 00 00 64 00 00 00 ........d...d... 0010 C7 00 00 00 C7 00 00 00 35 0C 00 00 35 0C 00 00 ........5...5... 0020 4B 18 00 00 4B 18 00 00 20 45 4D 46 00 00 01 00 K...K... EMF.... 0030 F0 0E 00 00 03 00 00 00 01 00 00 00 12 00 00 00 ................ 0040 64 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 04 00 00 00 03 00 00 d............... 0050 40 01 00 00 F0 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 @............... 0060 00 00 00 00 45 00 4D 00 46 00 34 00 00 00 45 00 ....E.M.F.4...E. 0070 4D 00 46 00 20 00 44 00 65 00 6D 00 6F 00 20 00 M.F. .D.e.m.o. . 0080 23 00 34 00 00 00 00 00 4D 00 00 00 54 0E 00 00 #.4.....M...T... 0090 64 00 00 00 64 00 00 00 C7 00 00 00 C7 00 00 00 d...d........... 00A0 64 00 00 00 64 00 00 00 64 00 00 00 64 00 00 00 d...d...d...d... 00B0 20 00 CC 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 80 3F ..............? 00C0 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 80 3F 00 00 00 00 ...........?.... 00D0 00 00 00 00 FF FF FF 00 00 00 00 00 6C 00 00 00 ............l... 00E0 28 00 00 00 94 00 00 00 C0 0D 00 00 28 00 00 00 (...........(... 00F0 16 00 00 00 28 00 00 00 28 00 00 00 16 00 00 00 ....(...(....... 0100 01 00 20 00 00 00 00 00 C0 0D 00 00 00 00 00 00 .. ............. 0110 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 C0 C0 C0 00 ................ 0120 C0 C0 C0 00 C0 C0 C0 00 C0 C0 C0 00 C0 C0 C0 00 ................ . . . . 0ED0 C0 C0 C0 00 C0 C0 C0 00 C0 C0 C0 00 0E 00 00 00 ................ 0EE0 14 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 10 00 00 00 14 00 00 00 ................

Figure 18-10. A partial hexadecimal dump of EMF4.EMF.

This metafile contains just three records—a header, a 0x4D (or

EMR_STRETCHBLT) record that is 0x0E54 bytes long, and an end-of-file record.

I won’t pretend to have deciphered what each and every field of this record

means. But I will point out the crucial key to understanding how GDI can translate the series

of function calls in EMF4.C to a single metafile record.

GDI has converted the original device-dependent bitmap to a

device-independent bitmap (DIB). The entire DIB is stored in this record, which accounts for its size. I

suspect that when it comes time to play the metafile and display the bitmap, GDI actually

uses the StretchDIBits function rather than

StretchBlt. Or, GDI could convert the DIB back to

a device-dependent bitmap by using

CreateDIBitmap and then use a memory device

context and StretchBlt for the display.

The EMR_STRETCHBLT record begins at offset 0x0088 in the metafile. The DIB

is stored beginning at offset 0x00F4 in the metafile and continues to the end of the record

at 0x0EDC. The DIB begins with a 40-byte structure of type BITMAPINFOHEADER. This

is followed at offset 0x011C by 22 rows of 40 pixels each. This is a 32 bit-per-pixel DIB,

so each pixel requires 4 bytes.

Enumerating the Metafile

When you wish to get access to the individual records of a metafile you use a process

called metafile enumeration. This is demonstrated by the EMF5 program shown in

Figure 18-11. This program uses a metafile to display the same image as EMF3 but works by using

metafile enumeration.

Figure 18-11. The EMF5 program.

EMF5.C

/*-------------------------------------

EMF5.C -- Enhanced Metafile Demo #5

(c) Charles Petzold, 1998

-------------------------------------*/

#include <windows.h>

LRESULT CALLBACK WndProc (HWND, UINT, WPARAM, LPARAM) ;

int WINAPI WinMain (HINSTANCE hInstance, HINSTANCE hPrevInstance,

PSTR szCmdLine, int iCmdShow)

{

static TCHAR szAppName[] = TEXT ("EMF5") ;

HWND hwnd ;

MSG msg ;

WNDCLASS wndclass ;

wndclass.style = CS_HREDRAW | CS_VREDRAW ;

wndclass.lpfnWndProc = WndProc ;

wndclass.cbClsExtra = 0 ;

wndclass.cbWndExtra = 0 ;

wndclass.hInstance = hInstance ;

wndclass.hIcon = LoadIcon (NULL, IDI_APPLICATION) ;

wndclass.hCursor = LoadCursor (NULL, IDC_ARROW) ;

wndclass.hbrBackground = GetStockObject (WHITE_BRUSH) ;

wndclass.lpszMenuName = NULL ;

wndclass.lpszClassName = szAppName ;

if (!RegisterClass (&wndclass))

{

MessageBox (NULL, TEXT ("This program requires Windows NT!"),

szAppName, MB_ICONERROR) ;

return 0 ;

}

hwnd = CreateWindow (szAppName, TEXT ("Enhanced Metafile Demo #5"),

WS_OVERLAPPEDWINDOW,

CW_USEDEFAULT, CW_USEDEFAULT,

CW_USEDEFAULT, CW_USEDEFAULT,

NULL, NULL, hInstance, NULL) ;

ShowWindow (hwnd, iCmdShow) ;

UpdateWindow (hwnd) ;

while (GetMessage (&msg, NULL, 0, 0))

{

TranslateMessage (&msg) ;

DispatchMessage (&msg) ;

}

return msg.wParam ;

}

int CALLBACK EnhMetaFileProc (HDC hdc, HANDLETABLE * pHandleTable,

CONST ENHMETARECORD * pEmfRecord,

int iHandles, LPARAM pData)

{

PlayEnhMetaFileRecord (hdc, pHandleTable, pEmfRecord, iHandles) ;

return TRUE ;

}

LRESULT CALLBACK WndProc (HWND hwnd, UINT message, WPARAM wParam, LPARAM lParam)

{

HDC hdc ;

HENHMETAFILE hemf ;

PAINTSTRUCT ps ;

RECT rect ;

switch (message)

{

case WM_PAINT:

hdc = BeginPaint (hwnd, &ps) ;

GetClientRect (hwnd, &rect) ;

rect.left = rect.right / 4 ;

rect.right = 3 * rect.right / 4 ;

rect.top = rect.bottom / 4 ;

rect.bottom = 3 * rect.bottom / 4 ;

hemf = GetEnhMetaFile (TEXT ("..\\emf3\\emf3.emf")) ;

EnumEnhMetaFile (hdc, hemf, EnhMetaFileProc, NULL, &rect) ;

DeleteEnhMetaFile (hemf) ;

EndPaint (hwnd, &ps) ;

return 0 ;

case WM_DESTROY:

PostQuitMessage (0) ;

return 0 ;

}

return DefWindowProc (hwnd, message, wParam, lParam) ;

}

This program uses the EMF3.EMF file created by the EMF3 program, so make

sure you run that one before this one. Also, you need to run both programs from within the Visual C++ environment so that the directory paths are correct. In WM_PAINT processing, the major difference

between the two programs is that EMF3 called

PlayEnhMetaFile, but EMF5 calls

EnumEnhMetaFile. You’ll recall that the

PlayEnhMetaFile function has the following syntax:

PlayEnhMetaFile (hdc, hemf, &rect) ;

The first argument is the handle to the device context on which the metafile is to be

rendered. The second argument is a handle to the enhanced metafile. The third argument

is a pointer to a RECT structure that describes a rectangle on the device context surface.

The metafile image is stretched to fit, but not exceed, this rectangle.

The EnumEnhMetaFile has five arguments, three of which are the same as those

to PlayEnhMetaFile (although the pointer to the RECT structure has been moved to the

end of the argument list).

The third argument to EnumEnhMetaFile is the name of an enumeration function,

which I’ve chosen to call EnhMetaFileProc. The fourth argument is a pointer to arbitrary data

you may wish to pass to the enumeration function. I’ve simply set this argument to NULL.

Now let’s take a look at the enumeration function. When you call

EnumEnhMetaFile, GDI will call

EnhMetaFileProc once for each record in the metafile, including the

header record and the end-of-file record. Normally the enumeration function returns TRUE,

but it could return FALSE to abort the enumeration process.

The enumeration function has five parameters, which I’ll describe shortly. In

this program, I just pass the first four to

PlayEnhMetaFileRecord, which causes GDI to

execute the function call represented by that record just as if you had called it explicitly.

EMF5 uses EnumEnhMetaFile and

PlayEnhMetaFileRecord to get the same results

as EMF3 got by calling PlayEnhMetaFile. The difference is that EMF5 now has a hook into

the process of metafile rendering and gets access to every metafile record. This can be useful.

The first parameter to the enumeration function is a handle to a device context.

GDI simply obtains this handle from the first parameter to

EnumEnhMetaFile. My enumeration function passes it on to

PlayEnhMetaFileRecord to identify the device context on

which the image is to be rendered.

Let me skip to the third parameter of the enumeration function. This is a pointer

to a structure of type ENHMETARECORD, which I described earlier. This structure

describes the actual metafile record, exactly as it’s encoded in the metafile itself.

You can write code to examine these records if you wish. Perhaps you might

elect not to pass some records to the

PlayEnhMetaFileRecord function. For example,

in EMF5.C, try inserting the following line right before the

PlayEnhMetaFileRecord call:

if (pEmfRecord->iType != EMR_LINETO)

Recompile the program, run it, and you’ll see only the rectangle, not the two

lines. Or try the following:

if (pEmfRecord->iType != EMR_SELECTOBJECT)

That little change will cause the image to be rendered with default objects—not

the pen and brush we’ve created.

One thing you should not do is modify the metafile record. But before you get

upset about this restriction, let’s take a look at the EMF6 program in Figure 18-12.

Figure 18-12. The EMF6 program.

EMF6.C

/*-------------------------------------

EMF6.C -- Enhanced Metafile Demo #6

(c) Charles Petzold, 1998

-------------------------------------*/

#include <windows.h>

LRESULT CALLBACK WndProc (HWND, UINT, WPARAM, LPARAM) ;

int WINAPI WinMain (HINSTANCE hInstance, HINSTANCE hPrevInstance,

PSTR lpszCmdLine, int iCmdShow)

{

static TCHAR szAppName[] = TEXT ("EMF6") ;

HWND hwnd ;

MSG msg ;

WNDCLASS wndclass ;

wndclass.style = CS_HREDRAW | CS_VREDRAW ;

wndclass.lpfnWndProc = WndProc ;

wndclass.cbClsExtra = 0 ;

wndclass.cbWndExtra = 0 ;

wndclass.hInstance = hInstance ;

wndclass.hIcon = LoadIcon (NULL, IDI_APPLICATION) ;

wndclass.hCursor = LoadCursor (NULL, IDC_ARROW) ;

wndclass.hbrBackground = GetStockObject (WHITE_BRUSH) ;

wndclass.lpszMenuName = NULL ;

wndclass.lpszClassName = szAppName ;

if (!RegisterClass (&wndclass))

{

MessageBox (NULL, TEXT ("This program requires Windows NT!"),

szAppName, MB_ICONERROR) ;

return 0 ;

}

hwnd = CreateWindow (szAppName, TEXT ("Enhanced Metafile Demo #6"),

WS_OVERLAPPEDWINDOW,

CW_USEDEFAULT, CW_USEDEFAULT,

CW_USEDEFAULT, CW_USEDEFAULT,

NULL, NULL, hInstance, NULL) ;

ShowWindow (hwnd, iCmdShow) ;

UpdateWindow (hwnd) ;

while (GetMessage (&msg, NULL, 0, 0))

{

TranslateMessage (&msg) ;

DispatchMessage (&msg) ;

}

return msg.wParam ;

}

int CALLBACK EnhMetaFileProc (HDC hdc, HANDLETABLE * pHandleTable,

CONST ENHMETARECORD * pEmfRecord,

int iHandles, LPARAM pData)

{

ENHMETARECORD * pEmfr ;

pEmfr = (ENHMETARECORD *) malloc (pEmfRecord->nSize) ;

CopyMemory (pEmfr, pEmfRecord, pEmfRecord->nSize) ;

if (pEmfr->iType == EMR_RECTANGLE)

pEmfr->iType = EMR_ELLIPSE ;

PlayEnhMetaFileRecord (hdc, pHandleTable, pEmfr, iHandles) ;

free (pEmfr) ;

return TRUE ;

}

LRESULT CALLBACK WndProc (HWND hwnd, UINT message, WPARAM wParam, LPARAM lParam)

{

HDC hdc ;

HENHMETAFILE hemf ;

PAINTSTRUCT ps ;

RECT rect ;

switch (message)

{

case WM_PAINT:

hdc = BeginPaint (hwnd, &ps) ;

GetClientRect (hwnd, &rect) ;

rect.left = rect.right / 4 ;

rect.right = 3 * rect.right / 4 ;

rect.top = rect.bottom / 4 ;

rect.bottom = 3 * rect.bottom / 4 ;

hemf = GetEnhMetaFile (TEXT ("..\\emf3\\emf3.emf")) ;

EnumEnhMetaFile (hdc, hemf, EnhMetaFileProc, NULL, &rect) ;

DeleteEnhMetaFile (hemf) ;

EndPaint (hwnd, &ps) ;

return 0 ;

case WM_DESTROY:

PostQuitMessage (0) ;

return 0 ;

}

return DefWindowProc (hwnd, message, wParam, lParam) ;

}

Like EMF5, EMF6 uses the EMF3.EMF metafile created by the EMF3 program, so

be sure to run that program before this one and run all programs within Visual C++.

EMF6 demonstrates that if you want to modify metafile records before

rendering them, the solution is fairly simple: you make a copy and modify that. As you can see,

the enumeration procedure begins by using

malloc to allocate a block of memory the size

of the metafile record, indicated by the

nSize field of the pEmfRecord structure passed to

the function. A pointer to this block is saved in the variable

pEmfr, which is a pointer to an ENHMETARECORD structure.

Using CopyMemory, the program copies the contents of the structure pointed to

by pEmfRecord to the structure pointed to by

pEmfr. Now we have something that we can alter. The program checks whether the record is of type EMR_RECTANGLE and, if so,

replaces the iType field with EMR_ELLIPSE. The

pEmfr pointer is passed to

PlayEnhMetaFileRecord and then freed. The result is that the program draws an ellipse rather than a

rectangle. Everything else is the same.

Of course, our little alteration worked quite easily because the

Rectangle and Ellipse functions have the same arguments that define the same thing—a bounding box for

the figure. Making more extensive alterations will require some knowledge about the

formats of the various metafile records.

Another possibility is to slip in an extra record or two. For example, replace the

if statement in EMF6.C with the following:

if (pEmfr->iType == EMR_RECTANGLE)

{

PlayEnhMetaFileRecord (hdc, pHandleTable, pEmfr, nObjects) ;

pEmfr->iType = EMR_ELLIPSE ;

}

Whenever a Rectangle record comes through, the program renders it and then changes it

to an Ellipse, which is also rendered. Now the program draws both a rectangle and an ellipse.

Let’s examine now how GDI objects are dealt with when you enumerate a metafile.

In the metafile header, the nHandles field of the ENHMETAHEADER structure is

a value of one more than the number of GDI objects created in the metafile. Thus, for

the metafiles in EMF5 and EMF6, this field is 3, accounting for the pen, the brush,

and something else. What this «something else» really is I’ll reveal shortly.

You’ll notice that the penultimate parameter to the enumeration functions in

EMF5 and EMF6 is also called nHandles. It’ll be the same number, which is 3.

The second parameter to the enumeration function is a pointer to a structure

called HANDLETABLE, defined in WINGDI.H like so:

typedef struct tagHANDLETABLE

{

HGDIOBJ objectHandle [1] ;

}

HANDLETABLE ;

The HGDIOBJ data type is a generalized handle to a GDI object and is defined as

a 32-bit pointer, as are all the other GDI objects. As you’ll note, this is one of those

structures that has an array field with just one element. This means the field is actually of

variable length. The number of elements in the objectHandle array is equal to

nHandles, which in the case of our programs is 3.

Within the enumeration function, you can obtain these handles using the expression

pHandleTable->objectHandle[i]

where i is either 0, 1, or 2 for the three handles.

Whenever the enumeration function is called, the first element of the array will

contain the handle to the metafile being enumerated. That’s the «something else» I

referred to above.

When the enumeration function is first called, the second and third elements of

the table will be 0. These are placeholders for the handles of the brush and the pen.

Here’s how it works: The first object-creation function in the metafile has a

record type of EMR_CREATEBRUSHINDIRECT. This record indicates an object number of 1.

When the record is passed to

PlayEnhMetaFileRecord, GDI creates the brush and obtains a

handle to it. This handle is stored as element 1 (the second element) of the

objectHandle array. When the first EMR_SELECTOBJECT record is passed to

PlayEnhMetaFileRecord, GDI notes that the handle number is 1 and is able to retrieve the actual handle from the table

and use it in a SelectObject call. When the metafile eventually deletes the brush, GDI sets

element 1 of the objectHandle array back to 0.

By accessing the objectHandle array, you can use calls such as

GetObjectType and GetObject to obtain information about the objects used in the metafile.

Embedding Images

Perhaps the most important use of metafile enumeration is to embed other images (or

even entire metafiles) in an existing metafile. Actually, the existing metafile remains

unchanged; what you really do is create a new metafile that combines the existing metafile and

the new embedded images. The basic trick is to pass a metafile device context handle as

the first argument to EnumEnhMetaFile. That allows you to render both metafile records

and GDI function calls on the metafile device context.

It’s easiest to embed new images at the beginning or end of the metafile

command sequence—that is, right after the EMR_HEADER record or right before the

EMF_EOF record. However, if you are familiar with the existing metafile, you can embed

new drawing commands anywhere you want. That’s what’s done in the EMF7 program

shown in Figure 18-13.

Figure 18-13. The EMF7 program.

EMF7.C

/*-------------------------------------

EMF7.C -- Enhanced Metafile Demo #7

(c) Charles Petzold, 1998

-------------------------------------*/

#include <windows.h>

LRESULT CALLBACK WndProc (HWND, UINT, WPARAM, LPARAM) ;

int WINAPI WinMain (HINSTANCE hInstance, HINSTANCE hPrevInstance,

PSTR lpszCmdLine, int iCmdShow)

{

static TCHAR szAppName[] = TEXT ("EMF7") ;

HWND hwnd ;

MSG msg ;

WNDCLASS wndclass ;

wndclass.style = CS_HREDRAW | CS_VREDRAW ;

wndclass.lpfnWndProc = WndProc ;

wndclass.cbClsExtra = 0 ;

wndclass.cbWndExtra = 0 ;

wndclass.hInstance = hInstance ;

wndclass.hIcon = LoadIcon (NULL, IDI_APPLICATION) ;

wndclass.hCursor = LoadCursor (NULL, IDC_ARROW) ;

wndclass.hbrBackground = GetStockObject (WHITE_BRUSH) ;

wndclass.lpszMenuName = NULL ;

wndclass.lpszClassName = szAppName ;

if (!RegisterClass (&wndclass))

{

MessageBox (NULL, TEXT ("This program requires Windows NT!"),

szAppName, MB_ICONERROR) ;

return 0 ;

}

hwnd = CreateWindow (szAppName, TEXT ("Enhanced Metafile Demo #7"),

WS_OVERLAPPEDWINDOW,

CW_USEDEFAULT, CW_USEDEFAULT,

CW_USEDEFAULT, CW_USEDEFAULT,

NULL, NULL, hInstance, NULL) ;

ShowWindow (hwnd, iCmdShow) ;

UpdateWindow (hwnd) ;

while (GetMessage (&msg, NULL, 0, 0))

{

TranslateMessage (&msg) ;

DispatchMessage (&msg) ;

}

return msg.wParam ;

}

int CALLBACK EnhMetaFileProc (HDC hdc, HANDLETABLE * pHandleTable,

CONST ENHMETARECORD * pEmfRecord,

int iHandles, LPARAM pData)

{

HBRUSH hBrush ;

HPEN hPen ;

LOGBRUSH lb ;

if (pEmfRecord->iType != EMR_HEADER && pEmfRecord->iType != EMR_EOF)

PlayEnhMetaFileRecord (hdc, pHandleTable, pEmfRecord, iHandles) ;

if (pEmfRecord->iType == EMR_RECTANGLE)

{

hBrush = SelectObject (hdc, GetStockObject (NULL_BRUSH)) ;

lb.lbStyle = BS_SOLID ;

lb.lbColor = RGB (0, 255, 0) ;

lb.lbHatch = 0 ;

hPen = SelectObject (hdc,

ExtCreatePen (PS_SOLID | PS_GEOMETRIC, 5, &lb, 0, NULL)) ;

Ellipse (hdc, 100, 100, 200, 200) ;

DeleteObject (SelectObject (hdc, hPen)) ;

SelectObject (hdc, hBrush) ;

}

return TRUE ;

}

LRESULT CALLBACK WndProc (HWND hwnd, UINT message, WPARAM wParam, LPARAM lParam)

{

ENHMETAHEADER emh ;

HDC hdc, hdcEMF ;

HENHMETAFILE hemfOld, hemf ;

PAINTSTRUCT ps ;

RECT rect ;

switch (message)

{

case WM_CREATE:

// Retrieve existing metafile and header

hemfOld = GetEnhMetaFile (TEXT ("..\\emf3\\emf3.emf")) ;

GetEnhMetaFileHeader (hemfOld, sizeof (ENHMETAHEADER), &emh) ;

// Create a new metafile DC

hdcEMF = CreateEnhMetaFile (NULL, TEXT ("emf7.emf"), NULL,

TEXT ("EMF7\0EMF Demo #7\0")) ;

// Enumerate the existing metafile

EnumEnhMetaFile (hdcEMF, hemfOld, EnhMetaFileProc, NULL,

(RECT *) & emh.rclBounds) ;

// Clean up

hemf = CloseEnhMetaFile (hdcEMF) ;

DeleteEnhMetaFile (hemfOld) ;

DeleteEnhMetaFile (hemf) ;

return 0 ;

case WM_PAINT:

hdc = BeginPaint (hwnd, &ps) ;

GetClientRect (hwnd, &rect) ;

rect.left = rect.right / 4 ;

rect.right = 3 * rect.right / 4 ;

rect.top = rect.bottom / 4 ;

rect.bottom = 3 * rect.bottom / 4 ;

hemf = GetEnhMetaFile (TEXT ("emf7.emf")) ;

PlayEnhMetaFile (hdc, hemf, &rect) ;

DeleteEnhMetaFile (hemf) ;

EndPaint (hwnd, &ps) ;

return 0 ;

case WM_DESTROY:

PostQuitMessage (0) ;

return 0 ;

}

return DefWindowProc (hwnd, message, wParam, lParam) ;

}

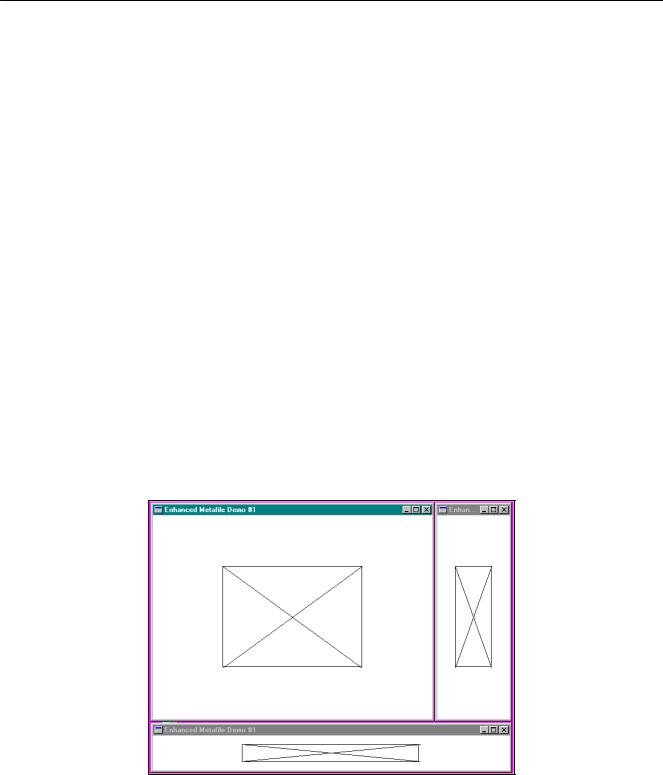

EMF7 uses the EMF3.EMF metafile created by the EMF3 program, so make sure

you run that program to create the metafile before you run EMF7.

Although WM_PAINT processing in EMF7 has reverted to using

PlayEnhMetaFile rather than

EnumEnhMetaFile, WM_CREATE processing is quite different.

First, the program obtains a metafile handle for the EMF3.EMF file by calling

GetEnhMetaFile. It also gets the enhanced metafile header by calling

GetEnhMetaFileHeader. The sole purpose of getting the header is to use the

rclBounds field in the forthcoming

EnumEnhMetaFile call.

Next, the program creates a new disk-based metafile to be stored with the

name EMF7.EMF. The CreateEnhMetaFile function returns a device context handle for the

metafile. Then EnumEnhMetaFile is called using the metafile device context handle for

EMF7.EMF and the metafile handle from EMF3.EMF.

Now let’s take a look at EnhMetaFileProc. If the record being enumerated is not

the header or the end-of-file, the function calls

PlayEnhMetaFileRecord to transfer the

record into the new metafile device context. (It’s not strictly necessary to exclude the header

or end-of-file record, but they make the metafile somewhat larger.)

If the record just transferred is the

Rectangle call, the function creates a pen

to draw an ellipse with a green outline and a transparent interior. Notice how the code

restores the state of the device context by saving the previous pen and brush handles.

During this time, all these functions are inserted into the metafile. (Keep in mind that you

can also use PlayEnhMetaFile to insert an entire metafile in the existing one.)

Back in WM_CREATE processing, the program calls

CloseEnhMetaFile to obtain a handle to the new metafile. Then it deletes both metafile handles, leaving behind both

the EMF3.EMF and EMF7.EMF files on disk.

It’s obvious from the program’s display output that the ellipse is drawn after

the rectangle but before the two crisscrossing lines.

An Enhanced Metafile Viewer and Printer

Using the clipboard for transferring enhanced metafiles is quite simple. The clipboard

type is CF_ENHMETAFILE. The

GetClipboardData function returns a handle to the

enhanced metafile; the SetClipboardData also uses the metafile handle. Need a copy of the

metafile? Use the CopyEnhMetaFile function. If you put an enhanced metafile in the

clipboard, Windows will make available a metafile in the old format for those programs that need

it. If you put an old-format metafile in the clipboard, Windows will make available an

enhanced metafile.

The EMFVIEW program shown in Figure 18-14 shows code to transfer metafiles

to and from the clipboard, and it also allows loading metafiles, saving metafiles, and

printing them.

Figure 18-14. The EMFVIEW program.

EMFVIEW.C

/*----------------------------------------

EMFVIEW.C -- View Enhanced Metafiles

(c) Charles Petzold, 1998

----------------------------------------*/

#include <windows.h>

#include <commdlg.h>

#include "resource.h"

LRESULT CALLBACK WndProc (HWND, UINT, WPARAM, LPARAM) ;

TCHAR szAppName[] = TEXT ("EmfView") ;

int WINAPI WinMain (HINSTANCE hInstance, HINSTANCE hPrevInstance,

PSTR szCmdLine, int iCmdShow)

{

HACCEL hAccel ;

HWND hwnd ;

MSG msg ;

WNDCLASS wndclass ;

wndclass.style = CS_HREDRAW | CS_VREDRAW ;

wndclass.lpfnWndProc = WndProc ;

wndclass.cbClsExtra = 0 ;

wndclass.cbWndExtra = 0 ;

wndclass.hInstance = hInstance ;

wndclass.hIcon = LoadIcon (NULL, IDI_APPLICATION) ;

wndclass.hCursor = LoadCursor (NULL, IDC_ARROW) ;

wndclass.hbrBackground = (HBRUSH) GetStockObject (WHITE_BRUSH) ;

wndclass.lpszMenuName = szAppName ;

wndclass.lpszClassName = szAppName ;

if (!RegisterClass (&wndclass))

{

MessageBox (NULL, TEXT ("This program requires Windows NT!"),

szAppName, MB_ICONERROR) ;

return 0 ;

}

hwnd = CreateWindow (szAppName, TEXT ("Enhanced Metafile Viewer"),

WS_OVERLAPPEDWINDOW,

CW_USEDEFAULT, CW_USEDEFAULT,

CW_USEDEFAULT, CW_USEDEFAULT,

NULL, NULL, hInstance, NULL) ;

ShowWindow (hwnd, iCmdShow) ;

UpdateWindow (hwnd) ;

hAccel = LoadAccelerators (hInstance, szAppName) ;

while (GetMessage (&msg, NULL, 0, 0))

{

if (!TranslateAccelerator (hwnd, hAccel, &msg))

{

TranslateMessage (&msg) ;

DispatchMessage (&msg) ;

}

}

return msg.wParam ;

}

HPALETTE CreatePaletteFromMetaFile (HENHMETAFILE hemf)

{

HPALETTE hPalette ;

int iNum ;

LOGPALETTE * plp ;

if (!hemf)

return NULL ;

if (0 == (iNum = GetEnhMetaFilePaletteEntries (hemf, 0, NULL)))

return NULL ;

plp = malloc (sizeof (LOGPALETTE) + (iNum - 1) * sizeof (PALETTEENTRY)) ;

plp->palVersion = 0x0300 ;

plp->palNumEntries = iNum ;

GetEnhMetaFilePaletteEntries (hemf, iNum, plp->palPalEntry) ;

hPalette = CreatePalette (plp) ;

free (plp) ;

return hPalette ;

}

LRESULT CALLBACK WndProc (HWND hwnd, UINT message, WPARAM wParam, LPARAM lParam)

{

static DOCINFO di = { sizeof (DOCINFO), TEXT ("EmfView: Printing") } ;

static HENHMETAFILE hemf ;

static OPENFILENAME ofn ;

static PRINTDLG printdlg = { sizeof (PRINTDLG) } ;

static TCHAR szFileName [MAX_PATH], szTitleName [MAX_PATH] ;

static TCHAR szFilter[] =

TEXT ("Enhanced Metafiles (*.EMF)\0*.emf\0")

TEXT ("All Files (*.*)\0*.*\0\0") ;

BOOL bSuccess ;

ENHMETAHEADER header ;

HDC hdc, hdcPrn ;

HENHMETAFILE hemfCopy ;

HMENU hMenu ;

HPALETTE hPalette ;

int i, iLength, iEnable ;

PAINTSTRUCT ps ;

RECT rect ;

PTSTR pBuffer ;

switch (message)

{

case WM_CREATE:

// Initialize OPENFILENAME structure

ofn.lStructSize = sizeof (OPENFILENAME) ;

ofn.hwndOwner = hwnd ;

ofn.hInstance = NULL ;

ofn.lpstrFilter = szFilter ;

ofn.lpstrCustomFilter = NULL ;

ofn.nMaxCustFilter = 0 ;

ofn.nFilterIndex = 0 ;

ofn.lpstrFile = szFileName ;

ofn.nMaxFile = MAX_PATH ;

ofn.lpstrFileTitle = szTitleName ;

ofn.nMaxFileTitle = MAX_PATH ;

ofn.lpstrInitialDir = NULL ;

ofn.lpstrTitle = NULL ;

ofn.Flags = 0 ;

ofn.nFileOffset = 0 ;

ofn.nFileExtension = 0 ;

ofn.lpstrDefExt = TEXT ("emf") ;

ofn.lCustData = 0 ;

ofn.lpfnHook = NULL ;

ofn.lpTemplateName = NULL ;

return 0 ;

case WM_INITMENUPOPUP:

hMenu = GetMenu (hwnd) ;

iEnable = hemf ? MF_ENABLED : MF_GRAYED ;

EnableMenuItem (hMenu, IDM_FILE_SAVE_AS, iEnable) ;

EnableMenuItem (hMenu, IDM_FILE_PRINT, iEnable) ;

EnableMenuItem (hMenu, IDM_FILE_PROPERTIES, iEnable) ;

EnableMenuItem (hMenu, IDM_EDIT_CUT, iEnable) ;

EnableMenuItem (hMenu, IDM_EDIT_COPY, iEnable) ;

EnableMenuItem (hMenu, IDM_EDIT_DELETE, iEnable) ;

EnableMenuItem (hMenu, IDM_EDIT_PASTE,

IsClipboardFormatAvailable (CF_ENHMETAFILE) ?

MF_ENABLED : MF_GRAYED) ;

return 0 ;

case WM_COMMAND:

switch (LOWORD (wParam))

{

case IDM_FILE_OPEN:

// Show the File Open dialog box

ofn.Flags = 0 ;

if (!GetOpenFileName (&ofn))

return 0 ;

// If there's an existing EMF, get rid of it.

if (hemf)

{

DeleteEnhMetaFile (hemf) ;

hemf = NULL ;

}

// Load the EMF into memory

SetCursor (LoadCursor (NULL, IDC_WAIT)) ;

ShowCursor (TRUE) ;

hemf = GetEnhMetaFile (szFileName) ;

ShowCursor (FALSE) ;

SetCursor (LoadCursor (NULL, IDC_ARROW)) ;

// Invalidate the client area for later update

InvalidateRect (hwnd, NULL, TRUE) ;

if (hemf == NULL)

{

MessageBox (hwnd, TEXT ("Cannot load metafile"),

szAppName, MB_ICONEXCLAMATION | MB_OK) ;

}

return 0 ;

case IDM_FILE_SAVE_AS:

if (!hemf)

return 0 ;

// Show the File Save dialog box

ofn.Flags = OFN_OVERWRITEPROMPT ;

if (!GetSaveFileName (&ofn))

return 0 ;

// Save the EMF to disk file

SetCursor (LoadCursor (NULL, IDC_WAIT)) ;

ShowCursor (TRUE) ;

hemfCopy = CopyEnhMetaFile (hemf, szFileName) ;

ShowCursor (FALSE) ;

SetCursor (LoadCursor (NULL, IDC_ARROW)) ;

if (hemfCopy)

{

DeleteEnhMetaFile (hemf) ;

hemf = hemfCopy ;

}

else

MessageBox (hwnd, TEXT ("Cannot save metafile"),

szAppName, MB_ICONEXCLAMATION | MB_OK) ;

return 0 ;

case IDM_FILE_PRINT:

// Show the Print dialog box and get printer DC

printdlg.Flags = PD_RETURNDC | PD_NOPAGENUMS | PD_NOSELECTION ;

if (!PrintDlg (&printdlg))

return 0 ;

if (NULL == (hdcPrn = printdlg.hDC))

{

MessageBox (hwnd, TEXT ("Cannot obtain printer DC"),

szAppName, MB_ICONEXCLAMATION | MB_OK) ;

return 0 ;

}

// Get size of printable area of page

rect.left = 0 ;

rect.right = GetDeviceCaps (hdcPrn, HORZRES) ;

rect.top = 0 ;

rect.bottom = GetDeviceCaps (hdcPrn, VERTRES) ;

bSuccess = FALSE ;

// Play the EMF to the printer

SetCursor (LoadCursor (NULL, IDC_WAIT)) ;

ShowCursor (TRUE) ;

if ((StartDoc (hdcPrn, &di) > 0) && (StartPage (hdcPrn) > 0))

{

PlayEnhMetaFile (hdcPrn, hemf, &rect) ;

if (EndPage (hdcPrn) > 0)

{

bSuccess = TRUE ;

EndDoc (hdcPrn) ;

}

}

ShowCursor (FALSE) ;

SetCursor (LoadCursor (NULL, IDC_ARROW)) ;

DeleteDC (hdcPrn) ;

if (!bSuccess)

MessageBox (hwnd, TEXT ("Could not print metafile"),

szAppName, MB_ICONEXCLAMATION | MB_OK) ;

return 0 ;

case IDM_FILE_PROPERTIES:

if (!hemf)

return 0 ;

iLength = GetEnhMetaFileDescription (hemf, 0, NULL) ;

pBuffer = malloc ((iLength + 256) * sizeof (TCHAR)) ;

GetEnhMetaFileHeader (hemf, sizeof (ENHMETAHEADER), &header) ;

// Format header file information

i = wsprintf (pBuffer,

TEXT ("Bounds = (%i, %i) to (%i, %i) pixels\n"),

header.rclBounds.left, header.rclBounds.top,

header.rclBounds.right, header.rclBounds.bottom) ;

i += wsprintf (pBuffer + i,

TEXT ("Frame = (%i, %i) to (%i, %i) mms\n"),

header.rclFrame.left, header.rclFrame.top,

header.rclFrame.right, header.rclFrame.bottom) ;

i += wsprintf (pBuffer + i,

TEXT ("Resolution = (%i, %i) pixels")

TEXT (" = (%i, %i) mms\n"),

header.szlDevice.cx, header.szlDevice.cy,

header.szlMillimeters.cx,

header.szlMillimeters.cy) ;

i += wsprintf (pBuffer + i,

TEXT ("Size = %i, Records = %i, ")

TEXT ("Handles = %i, Palette entries = %i\n"),

header.nBytes, header.nRecords,

header.nHandles, header.nPalEntries) ;

// Include the metafile description, if present

if (iLength)

{

i += wsprintf (pBuffer + i, TEXT ("Description = ")) ;

GetEnhMetaFileDescription (hemf, iLength, pBuffer + i) ;

pBuffer [lstrlen (pBuffer)] = `\t' ;

}

MessageBox (hwnd, pBuffer, TEXT ("Metafile Properties"), MB_OK) ;

free (pBuffer) ;

return 0 ;

case IDM_EDIT_COPY:

case IDM_EDIT_CUT:

if (!hemf)

return 0 ;

// Transfer metafile copy to the clipboard

hemfCopy = CopyEnhMetaFile (hemf, NULL) ;

OpenClipboard (hwnd) ;

EmptyClipboard () ;

SetClipboardData (CF_ENHMETAFILE, hemfCopy) ;

CloseClipboard () ;

if (LOWORD (wParam) == IDM_EDIT_COPY)

return 0 ;

// fall through if IDM_EDIT_CUT

case IDM_EDIT_DELETE:

if (hemf)

{

DeleteEnhMetaFile (hemf) ;

hemf = NULL ;

InvalidateRect (hwnd, NULL, TRUE) ;

}

return 0 ;

case IDM_EDIT_PASTE:

OpenClipboard (hwnd) ;

hemfCopy = GetClipboardData (CF_ENHMETAFILE) ;

CloseClipboard () ;

if (hemfCopy && hemf)

{

DeleteEnhMetaFile (hemf) ;

hemf = NULL ;

}

hemf = CopyEnhMetaFile (hemfCopy, NULL) ;

InvalidateRect (hwnd, NULL, TRUE) ;

return 0 ;

case IDM_APP_ABOUT:

MessageBox (hwnd, TEXT ("Enhanced Metafile Viewer\n")

TEXT ("(c) Charles Petzold, 1998"),

szAppName, MB_OK) ;

return 0 ;

case IDM_APP_EXIT:

SendMessage (hwnd, WM_CLOSE, 0, 0L) ;

return 0 ;

}

break ;

case WM_PAINT:

hdc = BeginPaint (hwnd, &ps) ;

if (hemf)

{

if (hPalette = CreatePaletteFromMetaFile (hemf))

{

SelectPalette (hdc, hPalette, FALSE) ;

RealizePalette (hdc) ;

}

GetClientRect (hwnd, &rect) ;

PlayEnhMetaFile (hdc, hemf, &rect) ;

if (hPalette)

DeleteObject (hPalette) ;

}

EndPaint (hwnd, &ps) ;

return 0 ;

case WM_QUERYNEWPALETTE:

if (!hemf || !(hPalette = CreatePaletteFromMetaFile (hemf)))

return FALSE ;

hdc = GetDC (hwnd) ;

SelectPalette (hdc, hPalette, FALSE) ;

RealizePalette (hdc) ;

InvalidateRect (hwnd, NULL, FALSE) ;

DeleteObject (hPalette) ;

ReleaseDC (hwnd, hdc) ;

return TRUE ;

case WM_PALETTECHANGED:

if ((HWND) wParam == hwnd)

break ;

if (!hemf || !(hPalette = CreatePaletteFromMetaFile (hemf)))

break ;

hdc = GetDC (hwnd) ;

SelectPalette (hdc, hPalette, FALSE) ;

RealizePalette (hdc) ;

UpdateColors (hdc) ;

DeleteObject (hPalette) ;

ReleaseDC (hwnd, hdc) ;

break ;

case WM_DESTROY:

if (hemf)

DeleteEnhMetaFile (hemf) ;

PostQuitMessage (0) ;

return 0 ;

}

return DefWindowProc (hwnd, message, wParam, lParam) ;

}

EMFVIEW.RC (excerpts)

//Microsoft Developer Studio generated resource script.

#include "resource.h"

#include "afxres.h"

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

// Menu

EMFVIEW MENU DISCARDABLE

BEGIN

POPUP "&File"

BEGIN

MENUITEM "&Open\tCtrl+O", IDM_FILE_OPEN

MENUITEM "Save &As...", IDM_FILE_SAVE_AS

MENUITEM SEPARATOR

MENUITEM "&Print...\tCtrl+P", IDM_FILE_PRINT

MENUITEM SEPARATOR

MENUITEM "&Properties", IDM_FILE_PROPERTIES

MENUITEM SEPARATOR

MENUITEM "E&xit", IDM_APP_EXIT

END

POPUP "&Edit"

BEGIN

MENUITEM "Cu&t\tCtrl+X", IDM_EDIT_CUT

MENUITEM "&Copy\tCtrl+C", IDM_EDIT_COPY

MENUITEM "&Paste\tCtrl+V", IDM_EDIT_PASTE

MENUITEM "&Delete\tDel", IDM_EDIT_DELETE

END

POPUP "Help"

BEGIN

MENUITEM "&About EmfView...", IDM_APP_ABOUT

END

END

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

// Accelerator

EMFVIEW ACCELERATORS DISCARDABLE

BEGIN

"C", IDM_EDIT_COPY, VIRTKEY, CONTROL, NOINVERT

"O", IDM_FILE_OPEN, VIRTKEY, CONTROL, NOINVERT

"P", IDM_FILE_PRINT, VIRTKEY, CONTROL, NOINVERT

"V", IDM_EDIT_PASTE, VIRTKEY, CONTROL, NOINVERT

VK_DELETE, IDM_EDIT_DELETE, VIRTKEY, NOINVERT

"X", IDM_EDIT_CUT, VIRTKEY, CONTROL, NOINVERT

END

RESOURCE.H (excerpts)

// Microsoft Developer Studio generated include file. // Used by EmfView.rc #define IDM_FILE_OPEN 40001 #define IDM_FILE_SAVE_AS 40002 #define IDM_FILE_PRINT 40003 #define IDM_FILE_PROPERTIES 40004 #define IDM_APP_EXIT 40005 #define IDM_EDIT_CUT 40006 #define IDM_EDIT_COPY 40007 #define IDM_EDIT_PASTE 40008 #define IDM_EDIT_DELETE 40009 #define IDM_APP_ABOUT 40010

EMFVIEW also has complete palette logic, just in case a palette has been

encoded in the metafile. (The way it gets in there is by a call to

SelectPalette.) The program extracts the palette in its

CreatePaletteFromMetaFile function, which is called when it displays

a metafile during WM_PAINT and also while processing the WM_QUERYNEWPALETTE

and WM_PALETTECHANGED messages.

In response to a Print command from the menu, EMFVIEW displays the common